Here’s our first gathering to prepare for Primetime Adventures, a game whose title will invoke more blithering, partisanship, and sprayed terminology than any other I can think of. Which is too bad because the actual game is quite wonderful.

I ask pretty seriously that you examine the short presentation in Discuss: Primetime chat, and if you feel investigative, the discussion in Monday Lab 3: Boiling pitch.

We’re using the 2nd edition. In this session, you’ll see us create the series from scratch, i.e., no imposed prior content from me, make the protagonists, and play the pilot. It adds up to a beast of almost 200 minutes, including a short sequence I recorded afterwards and placed between preparation and play.

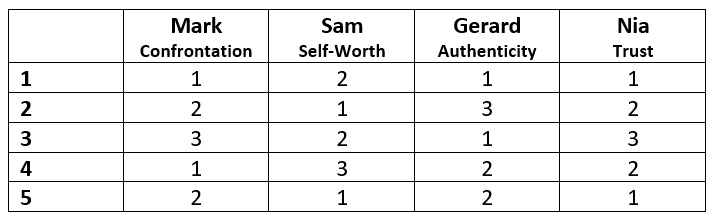

For reference, here’s a summary of the protagonists’ Screen Presence and issues. In the days following the session, people sent me pictures of their characters and I arrived at a name for the series. I’m restraining myself from providing my notes following play, including which rules I think we need to review a bit and what I have in mind for Episode 1; I’ll share those after that episode gets recorded and posted here.

For reference, here’s a summary of the protagonists’ Screen Presence and issues. In the days following the session, people sent me pictures of their characters and I arrived at a name for the series. I’m restraining myself from providing my notes following play, including which rules I think we need to review a bit and what I have in mind for Episode 1; I’ll share those after that episode gets recorded and posted here.

Please ask questions. I am sadly almost fully certain that no one reading this has seen the game played this way before.

17 responses to “Our series begins”

Resolution and narration

I've run the game this way and also been a player in games like this.

At the same time, I've always been uncomfortable with the resolution system. On reflection, I think I've been looking for action-by-action bounce and feeling there was something wrong because it didn't work that way. It's reassuring to see that I was playing it correctly. I guess I never completely embraced the scene resolution system.

Question: in part 10 when Sandra's character Nia is probing into the secret lab — you asked what kind of thing she hopes to find. She won both the conflict and the narration. She narrated finding information on a secret base. It seems that the conflict resolution provided the general parameters of outcome authority and the narration gives the high card winner authority to narrate the outcome details, as well as background authority. Do I have that right?

First, thanks for watching

First, thanks for watching this thing. Note to self, no more marathon sessions.

For your question – that is a very good point. Our transition into the episodes necessarily includes some review on that exact moment.

The simple answer is this: narration does not convey backstory authority. The tricky part is that during this pilot, given the lack of prep, we don't really have much content as raw material, so describing or narrating anything sort of puts us in that zone of authority, without wanting to be there.

Now, Sandra threw us a curveball, too. She was the very person who said, "I like it when it's about nothing," and then played Nia as obviously proactively investigating something. I suppose, table-talk wise, I could have interjected to ask her what she (Sandra) wanted to be happening (to be taken as a "suggestion" for the Producer, who in this case would have happily picked it up and incorporated it. I did ask her what Nia thought she was looking for or seeking, but didn't press it hard.

The reason why not is that the precise content ("what they're up to") is not actually all that big a deal, considering that, as I see it anyway, any scientific-industrial concern such as the one she gatecrashed would be up to something dodgy. So my quick-in-in-the-moment processing resulted in my conclusion that we can leave the precise nature of the intel as a McGuffin. For me, the important thing is that she trusted Sam to keep quiet about the whole thing, even when Sam ended up taking some heat for it.

Anyway, I consider this particular curveball effect to be part of the learning curve for our group to establish clearer roles among us for backstory content, and also how table-talk provides ideas for any of us to use while utilizing those roles. I'm OK with discovering any such points during the pilot, in fact, better than OK.

It’s not a Writers’ Room

For years I had no interest in PTA. There was no particular system or social reasons, I just had no interest in the game itself.

And the previous discussion about the game, while interesting, still did not motivate me towards any real interest other than the idea that "that game is not a writers' room. The characters are the characters and not writers, writing the characters."

Of course the power of PLAY and of seeing it in action often leads to "Oh, okay, yes I DO want to play that." This is the case here. I am putting PTA on my list of games I want to play, as a player, but of course also run. Which is unusual for me as my default is "yeah I would like to run that."

As a pure audiance member, there were moments of "what are you doing!?" in response to the character's actions, but not in a critical "you did it wrong" kind of way. In that visceral, tense, OMG I cannot belive they did that, but I enjoyed it kind of way. Playing with idiom and trope seems like a lot of fun.

My only question is about the success/failure state. It looks something like: seccuess = you get what you want and failure = you get more to work with. Is that accurate? And I grok'd how the mechanics work, so its not necessarily a mechanical question.

You’re seeing some of the

You're seeing some of the learning curve in action. I'll be specifying more clearly that conflicts' outcomes flatly, non-ambiguously succeed or fail at the protagonist's attempted outcome, and that failure carries consequences which must be narrated. Narration does have unique power; one person narrating the failure to fix the scoop might say that 100 people are killed, whereas another might say that one person is injured. But it can't slither out of failure, and our proper episodes will hold to that standard.

Episode 1!

We have played Episode 1, linked directly within the playlist. It begins with my presentation of my thoughts between sessions. When the session begins, we did go over all those things, but I didn't include it due to the repetition.

I set up a sheet of paper on my desk to show a box marked Budget, another marked Audience Pool, and then four smaller boxes marked with the players' names. I used dice as counters to track the movement from Budget to Pool to Fanmail, then sometimes back to Budget. Some of the players did the same, so that we would occasionally check the values.

Everyone was clear on the Audience/Fanmail process, and after just a little prompting for retroactive Fanmail, then it clicked as a habit and the cards were up and running.

As it happens, the Budget was replenished enough to stay at a few dice by the time the plot-events had reached their own conclusion, which is legal/fine. I do like it when the Producer runs out of Budget entirely, though, because then the players can seize the day and enjoy some triumphant conflicts.

some notes (to myself)

So now we shot the first episode and I realized a couple of things

Remember when you chose an issue, TV is a visual medium and you will have to transfer your issue into visual (or at least verbal) clues. Clearly I made a bad choice, I do know the issue by heart but forgot how difficult it is to transform it into palpable clues. I found myself at least twice describing what Sam thinks/feels and given the environment (TV-show) that should not happen.

Remember that when playing online, you will have to describe a lot more than when playing at a table. At the table everybody can see the sparkle in my eyes and my body language, on screen they can’t. Particularly there is a scene between Sam and Cara (her connection) where I realized long after, I should have described the way Sam looked at Cara and reacted to the situation in considerable detail. Unfortunately I did nothing of that kind which wasted a lot of potential.

Remember, people may say on thing and mean another, like “I like TV shows where nothing happens” and playing a hell of an action movie or “I want a space show” and putting up some kind of spy thriller. I think I’m fine with it, but it makes me still somewhat insecure in play.

And something on a much lighter note: Remember, whatever you may come up with for a character, with this group there is no “easy, laid back” way of play for you. It’s gonna heat up pretty fast, so get used to it.

Summary: This will be the first TV show I will finish watching, that is for sure.

Everybody out there, I know you’re watching, come and comment here, especially your thoughts about PTA as a game and your own experiences, please, part of the fun for me is comparisons and other peoples experience.

Helma/Sam

A few observations

Done with the pilot, and really curious about episode one. It takes a moment to get going, but in the end it was one of the most immediately enjoyable (in terms of pure entertainment) sessions I've seen recorded.

A few observations:

For your point #1, yes and no

For your point #1, yes and no. The key is stopping early, before anyone has the sense that it’s enough. It’s crucial not to let this topic run rampant before play, or else “the pitch” becomes “the series bible” and drains all the energy. The original creators of Star Trek didn’t give a shit about how the transporter works and neither should you.

For your point #2, Are you familiar with the variety of narration rules across The Pool, InSpectres, Dust Devils, and Trollbabe? They are all different, and each one’s details are highly specific and integrated with the rest of the respective system. Furthermore, consider Sorcerer and My Lie with Master, which emphatically do not include rules for narration, not even a default “GM says,” and that too is for good reasons within each game.

I'm composing some thoughts in reply to your #4 and will post them later.

#1 feels clear. How it looks,

#1 feels clear. How it looks, not how it works. The cultural frame of references play an interesting role – the moment you said "think Alien (not Aliens)" I was immediately onboard and knew I wasn't going to hear about holographic keyboards and replicators. I have some further thoughts on this but I'll save them for once I've seen more of the game.

#2 is… complicated. Yes, I'm familiar with those games, aside from InSpectres (I mean I know what it is, but I never read or played it). I've been borrowing Trollbabes' approach for most of the games I've run (that didn't have specific prescriptions on how to do it). I particularly like it because it's airproof in terms of the flow of information (players perfectly know the boundaries of failure before rolling, and the DM doesn't bring in any unwanted baggage; while he can extend success through his authorities without ever entering those "gotcha" moments that are unpleasant to me).

The thing is – knowing how it works or how it's written or how it should work is one thing. Making it work isn't always as easy. I'm saying this from the DM perspective (honestly I've played nonstop once or twice a week for most of my life and still do, but I think I've sat at a table as a non-GM 5 times in the last 10 years).

When I propose these solutions to the 5-6 people I generally play with I know two will have no issues doing it, one will do it but not enjoy for the reasons detailed ("I want ownership of my character only"), one will absolutely freeze and become unable to do anything with it (I mean literally – he's played for 30 years and he just can't process having to narrate something that isn't direct consequence of his character's choice); then there's the guy who'll joyfully take the narrative authority and immeditately turn it into background, situation and outcome authority if you don't stop him fast enough (spoiler: he's the guy who loves Blades in the Dark).

And so my comment was on the tone of: wow, watching this is play makes me think this could work at my table. I think what I'm particularly appreciating is the softened way in which the "this is fiction!" element is brought in the game, compared to the "You're not the character, you're an actor! And the screenwriter! And the audience!", in-your-face way that was used when I experienced the game locally.

Episode 2!

Direct link here into the playlist.

Content matters. In this game, some content is inherently present in the Premise, some is inherently present across the sheets of the protagonists. From there, it's apparently filtered out among gamer-dom that content appears at the opening of scene, de novo as authored by each player at that time.

That's not the case. Plenty of situation is determined at that point, up to and including skipping over incidental content ("the location is inside the vault" after the last scene we saw was planning the heist, for example). But that's not content in terms of setting variables, not even a little.

Take a look at the authorities this time around. We should talk a bit about it. Because it's not different from most, probably all role-playing you're familiar with.

Episode 3! well, half of it

Here's the direct link into the playlist. I had a lot to reflect upon or showcase so added a video of mine at the end as well.

Second half of Episode 3!

In this part, keep an eye on the setup for each scene. The game permits or encourages a certain amount of "how-about" at this point but does not throw it completely into consensus or workshopping. I can spot a few places where I took steps to maintain that boundary, so that suggestions can be made but the specific person's authority remains in place.

Also, at one point, I mention that I really don't want to be narrating the outcomes of so many contests. The cards' statistics per contest don't necessarily favor the Producer for the high card, but since I'm in every contest, even a less-than-even chance will still have me narrating more of the contests throughout a session.

Another structural thought: the rules mention that each person in play will likely frame several scenes, in a single session. Which is a lot of scenes! I think this may have been written in the context of assuming four hours of play. For us, in two hours, we manage to squeeze in one scene per person.

This series is worth watching

This series is worth watching for many reasons. Several months ago, I initially watched the first episode in small chunks due to stress and time constraints of my own combined with a certain resistance (in me) produced by the group's learning process. Not the easiest watching if you aren't prepared to take part in their (very natural) learning curve at the beginning , but it is that process that makes the viewing not a simple entertainment or a spoon-fed showcase of the game, but engaging material for my learning. One of the interesting things both about the game Primetime Adventures and this series of videos is that it is very clear about and exposes its functional distribution of the authorities. If you would base research into role-playing on this, you probably wouldn't make simplistic and wrong-headed conclusions similar to "In role-playing, the GM is the final arbiter on what gets established in the fiction".

The protagonist/PC Mark has a great, I would say transforming voyage in the third episode (both parts). His Issue (a rules term) about non-assertiveness/assertiveness is very much part of it. Max, the player, is killing it, and it’s wonderful to see this group interact.

It seems like the mechanics of the game is working with and rewards engagement with its initial promise or inspiration of "let's play a tv-series!" The group's table talk, meaning not discussions or negotiations about what should happen next but their running comments, facial expressions, gestures, etc, seems to build upon their shared understanding and celebration of the fictional activity to a degree that I haven’t seen in my play, ever. Not so “explicit” at least, if that’s the right word. They are like an excited, thinking audience, and that is interacting well with the fan mail mechanic. The fact that every scene is framed by a different person and begins with a very simple but concrete description of the locale (and then on to movement/doing), also seems to have something to do with it. And the people themselves, of course.

The fan mail has surprisingly many moving parts or sub-mechanics. Most of all, It seems like the excitement comes first, and then the fan-mail mechanic is a nice celebration of what excites the people. Spending of fan mail is also nicely, bouncily connected to narration authority. As I continue to watch, I want to study how the presence and amount of mail per player and in the audience pool interact with play.

I appreciate your comment

I appreciate your comment very much! These are all features I'd hoped to share with the community here, and it's been a painful wait for anyone to get past the pilot and the initial learning. One thing I'll never do in play is "sing for my supper," i.e., be as entertaining and smooth as possible for the future viewing audience, or to encourage others to do so. What you see here is people playing.

At this point in the sequence, I think it became clearer to everyone at the table just how the situational authorities are distributed. Sure, Nia can look for "whatever's happening" or "bad stuff going on," and according to narration may find something, but ultimately what that content may be is up to the Producer. Also, the Producer may introduce all manner of content both in specific scenes and in terms of the overall situation (episode or season). PTA play includes a rather familiar role for the GM, fancy name or not, and very little if any of the presumed "players make up what's happening and what happens" which seems to be culturally associated with the game.

Episode 4!

We began with some discussion I didn't include in the editing, including topics like changing one's Issue following a Spotlight (allowed, no one wanted to), and whether we'd change the narration rules so it didn't land with me all the time (no; maybe some other time playing the game).

I've been looking forward to the content concerning Marc's father's job and also concerning the threat or action-thriller nature of the Midnight Truth, and this episode coincidentally brought both of them together in a nice one-two punch.

Die Geister die ich rief …

Before I really start, something about myself: I come from a family whose would do a running commentary to every film and show they watched on TV. And believe me, we were very good at condemning love stories getting in the way of adventure and heroines that could not help themselves but would need some guy to rescue them, we made fun of it all and had a blast doing it.

Nowadays I seldom watch TV and I seriously doubt I have finished watching a TV-series in years, most of them for me get pretty predictable and boring after a while.

And here I am now, putting all the things I used to make fun of into the creation of a TV-show character and to be honest, having a lot of fun with it? When did I loose my bite, or is doing so fundamentally different from watching the result?

Well, to be completely honest, I don’t know exactly what happens. I kind of drifted into it while we were playing, first there was the idea that it would be nice to have a contrast to the “action driven spy thriller” thing everybody else had going. Then it became obvious that the others developed an interest for Sam’s little side story and everybody seemed set on it getting a (the muses help me) happy end. Whether they got it? go and watch the show. But remember, this was not the last episode.

Now I wonder. Is it ok or not to just produce another TV-show that follows established plot development. If somebody would describe Sam’s story to me I would deem it ridiculous and kitschy. Is there something special in this I do not see? Don’t get me wrong, I absolutely like playing PTA and looked forward (still do) to continuing the show, but I am surprised how everything played out for Sam and struggling to see what different decisions I could have made that would have led down another road while still following some kind of inner logic and character developement.

Let me know your thoughts.

Fotnote: the title is a citation from W. Goethe “Der Zauberlehrling”, unfortunately I can not come up with a really good translation, word for word it says “the spirits I called …” and the poem continues with how the protagonist cannot get rid of said spirits when it becomes apparent that they cause more trouble than help him accomplish his tasks.

Episode 5: season finale!

We have finished the season, and here is the final episode.

We also took some time to reflect on the experience, which is included at the end of the playlist.