I’ve been working up a Design curriculum for role-playing for a long while, so when Justin Nichols approached me for a game design discussion that leaned toward mentoring, I accepted without reservation.

At the beginning of this episode, we considered our options for the initial approach, and Justin preferred the “lab” version in which we actually worked on a design of his, called Kinfolk. So you’ll see some of the techniques from the Consulting section of the site used here, but it’s specifically a subroutine of the Seminar goals.

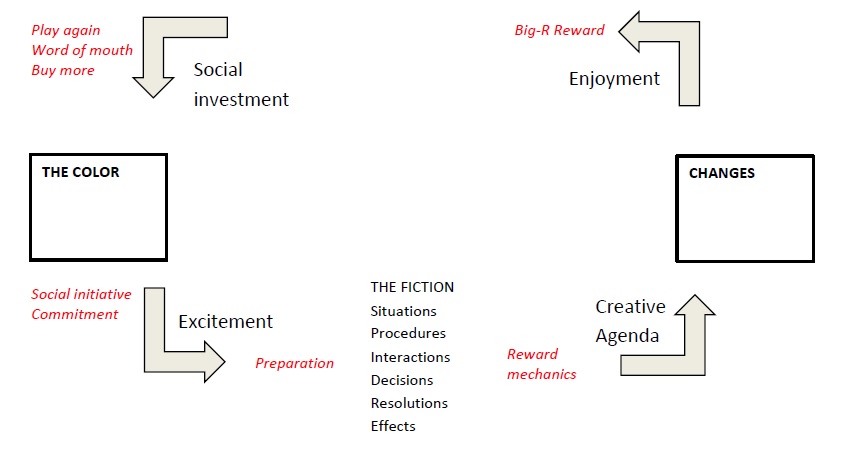

I’m drawing upon my Phenomenology videos, which I would be happy to see anyone review and comment upon. If you’re seen them, this leading diagram will be familiar to you. The idea is that you may begin playing the game based on partial or potential excitement, and the question is whether the game experience confirms and enhances this excitement to become real inspiration, creatively and socially.

A game’s design matters (rather than its subcultural identity or any other criteria) insofar as the procedures during play confirm the excitement, i.e., the content that initially prompted excitement was honest, the procedures result in changes of some kind, and the changes are themselves inspiring. The question is whether the procedures really do this, as instruments of human agency, or whether they are merely “Jesus is coming, look busy” pseudo-toys to fiddle with while someone else does it.

I usually introduce these ideas to people using a version of this diagram without all the fiddly terms, especially the stuff under “the fiction.” That way I can get the basic idea across without distraction and then the other people can work through the idea that simply being told the fiction isn’t good enough, that somehow, the fiction must be produced through some kind of activity, which may or may not actually work.

To do that, I focus on what changes, fictionally. Then tracking backwards to see if the procedures did it is intuitive, clear, and instructive.

There are two other recent pieces which serve as a cross-reference, perhaps even crucial ones. The first is my presentation at Lucca, The Plot Thickens, and the other is my consulting session about Heroic Dark. The latter and this session are complementary as the two games being discussed are coincidentally very much alike. Since we talked about different things in each one, viewing both works well.

One last minor point: looking over this session, I think the beginning-middle-end Fortune concept was not too helpful, because it was originally conceived in the context of single resolutions, not overall session outcomes. So feel free to edit that mentally.

6 responses to “Design Curriculum 1: Re-inspiration”

Tons of Great Material Here

I filled up pages of notes with what you've covered in this hour ten.

That’s great! Except …

That's great! Except … since I'm feeling my way through the topic, I bet there are plenty of mis-phrasings or false starts that you may be enshrining. Perhaps we could have a winnowing discussion some time.

I'm also interested in distinguishing carefully between training for design competence and understanding design from an analytical standpoint.

The trouble with that is the utter toxicity of the reader ("student") standpoint. From that perspective, the first would be filled with certainties and result in a sense of security, "trained-ness," and validation; and the second would filled with zinger questions, expansions, insulation against practical problems, and perhaps super-secrets. The usual undergrad/grad construct, or perhaps, catechism vs. seminary school, or the stereotype of doer vs. talker. "Just tell me how so I can get paid for doing this, why are you gatekeeping me," and, "Oh boy, I can sling bullshit and get paid for it? Model that for me and I'll join your entourage until I find my own branded line."

So, much as with science, martial arts, or nearly anything else that makes rather brutal sense in the actual world, acknowledging the difference between training and understanding is crucial, but requires intensive re-orientation as early as possible.

Yeah, I don’t know. Isn’t

Yeah, I don't know. Isn't that helpful?

My road to this point has been pretty jagged, as I imagine most people's are. I played games, I read your Forge essays, I played games, I read through Vincent's anyway blog, I read games, I followed people's thoughts and threads on G+ and Twitter, and now I'm here. So I guess at this stage, I have amassed a ton of knowledge and am collecting more while trying to sort it all out so that dots are connected and the wiring is solid–so that lights that occasionally flicker on can stay on and let me see more consistently.

This series is helping me look at that wiring and make secure connections. That's what I'm really enjoying about it.

It seems like starting with the cycle of inspiration and re-inspiration is a great thing to do. Tying that cycle to the major question of what meaningful changes occur through play (be they at the character level, setting level, or something else) is an ideal wide-angle view from which to see the entirety of the playing field and the ends to which all of RPG design's means need to lead.

I made notes of all the potential false leads and stray bits of insight as well because I know they'll be coming up in future sessions as you focus in on various aspects.

As for the student problem, I don't know if you can actually separate the two categories you name. Anyone wanting to design needs to know about the principles behind good design, and anyone learning about the principles of good design will either eventually be making a game of their own or the process of thinking through a game, even someone else's, is the best way to make those principles make sense. That's the case for teaching any art form. I can read about the principles of graphic design and web design, but who learns that just for the abstract? Even if I'm just using it to make the invite to my kid's party look bitchin', I'll be putting what I learn to use in some way. You're teaching this, rightly I think, as an art, rather than as a science.

Always happy to talk about anything that's helpful to you. I can even send you pictures of my notes, if you'd like to see what I'm taking away, which is a lot. Let me know what would be useful to you and I'll see what I can do.

We should revisit that

We should revisit that distinction from scratch, perhaps in screen dialogue. In text, here, I find myself blithering about "but what I meant was," and that's always a sign to stop and find a different way.

The rubber hits the road

Ron, if I understand you, you're talking about what I experienced in a clinical masters program — you learn theory and how to ask questions based on theory, but the actual doing brings both a perspective shift and a demand for pracical skills that aren't mentioned in theory. Learning how to put theory into practice is an experimental cycle: — try a technique in the real world, see the results it produces, relate that to theory, use the theory to guide use of the technique, repeat from the beginning. One doesn't get an intuitive understanding for how the techniques and theory relate without experiencing how they manifest in practice. Experience produces the best guide to learning when to use a technique. Have I just reinvented your rationale for a focus on actual play?

Yes, mostly. The “actual play

Yes, mostly. The "actual play first" had more to it pertaining specifically to the Forge at the time, concerning the surge of posturing bullshit that had begun to fill the RPG Theory forum, and the reasonable claim that people felt they were encountering an arcane wall of whatnot when they arrived. Not only was it better to discuss the ideas via play experience, it was also possible for anyone to post about play experience and it could be discussed in the language they wanted. And if people were committed to their individual versions of false general terms like "immersion," and "exploration," then we could use those local versions accurately by seeing what they meant in play for those people.

As a point specific to this forum, I am claiming that we can find access to one another's enjoyment of play via sharing our experiences, as well as learn about our differences in a non-hostile way, a concept which is no doubt familiar to you in social, psychological, and emotional context. Once that access is established, then ideas of interest may be raised and addressed if and when people want.