A few months ago, I asked participants at the Patreon to focus some play-time toward Cold Soldier, preferably played in person. I’d hoped to see more posting about it here as well.

I think I may still see that hope fulfilled, because I know there was a lot of play. In fact, Noah asked me if I’d like to play it with him, and I said, “But I’d prefer you to play it in person, not by screen,” and he said, “I’ve done that three times already,” meaning, since my request at the Patreon. All right then, so we did.

I wanted to play the Soldier for once (and I’ll probably do so for the foreseeable future, because I really liked it), and Noah chose The past and Vengeful god, specifying pretty far-ancient Greece. Or rather, Hellás, with an acknowledged strong influence from Gene Wolf’s Soldier books.

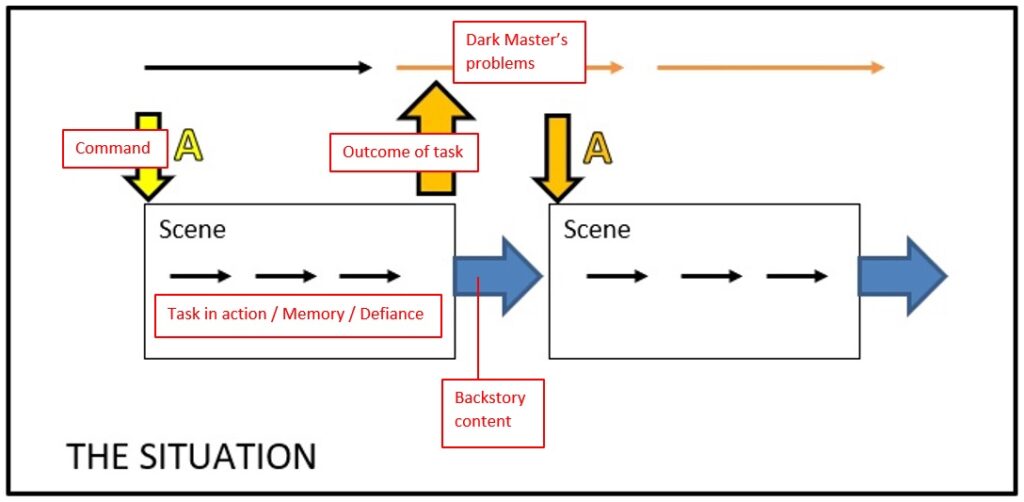

A lot of you are probably wearily familiar with this diagram by now, but perhaps its utility can be illustrated by mapping this game’s concentrated procedures into place.

If you review the rules for each of those red labels and perhaps your own experiences of play, I think you’ll see that playing the Dark Master is in no way “GMing” in the sense of the more secure person presenting a story or a series of challenges to the on-the-spot other (like a pitcher vs. a batter). If anyone’s being hit hard in terms of gearing up into major character play in the face of changing and probably traumatic circumstances, it’s the Dark Master player.

I draw your attention as well to the “inside the scene” box, to focus on the interacting authorities when we are not pulling out the cards and moving into resolution. … i.e., the “blanks” between the little black arrows, and what one of these arrows is like when it doesn’t require the cards. Since this diagram doesn’t deal with fine-grained interactions of this kind, I suggest making your own summary or schematic for (1) what each person is supposed to say without being asked and (2) what each person is supposed to ask in order to be able to say something.

Here are some thoughts which arose from our game, as we discussed later:

- Noah veered into starting to sympathize with his maddened nymph, in the sense that maybe she had been wronged – which is understandable because if one’s Dark Master is merely crazy, they’re no fun to play – but also to be avoided past a certain point, as the mandate to order the Soldier to do things that you personally think are vile is critical. One shoul seek to play, not a “good bad guy,” but a bad guy well.

- I definitely got a bit confused about who was who, and what had or had not been established, so made an effort to get oriented about halfway through.

- Related to that, I also found myself becoming too invested in making the Soldier’s backstory, above and beyond focusing on the established memories and finding new ones. In other words, dreaming up what has happened in order to establish details as memories later. Fortunately I spotted it as a danger; you can see me literally stop and clear my mind from doing it in the last few scenes of play.

To patrons or anybody who’s recently played Cold Soldier, please post about it! I’d like to develop some content and activities here based on substantial and various communal experiences.

In fact, let’s make sure everyone’s invited. The attached file is the game rules, exactly as designed by Bret, but with the text of the 2011 publication revised/re-organized by me, with his permission. Play & post please!

5 responses to “Death and blasphemy in ancient Hellás”

This playthrough sold me on Cold Soldier in a way previous ones I have been exposed to have not. I was surprised, a bit, by how little angst Ron’s soldier had, until the conversation at the end.

I am a believer that if a character has background elements, they are not and should not be treated as prophecy or even as concrete history. Characters are unreliable narrators. And having holes in the background allows the GM to fill them in…

BUT I come away with a different feeling or thought after the play. I think it can be best summed up as: the game or the procedures can fill in details about a character or characters through play. Small revelations as opposed to giant prophecy.

Maybe I read too much into that last part, but its given me something to mull over.

I’m trying to understand your contrasted concepts better. Do I have this right?

There are gaps or possibilities in a character’s backstory, and someone (probably a GM) fills them in and weaves them together with everything else that’s happening. This is done prior to play, for the most part, as a vision of how play will go and what will be discovered.

There are gaps or possibilities in a character’s backstory, which may or may not be filled or completely understood, and the extent to which this occurs is a matter for disconnected events during play, including their content.

I have designed games and played many games which feature both, or combinations between them. The question to me isn’t “can this work” at all, nor to contrast them as significantly different; but merely, “how does it work this time.”

But let me me know if I’m even at the starting gate for what you’re reflecting upon.

Yes I think those summations work for me. In particular the second part where the character can come more fully into view through or is fleshed out from play. But more than merely experiencing or hearing about a piece of content and incorporating it because its “cool”.

OK. I’m still feeling my way through your point, or maybe you’re still working it out so it’s not in place yet.

Given that summation … these are, surely, not utterly opposed concepts, correct? Certain things may be fixed in place, at the most extreme, from the start; certain things may be open/unknown (and known to be available for filling by the person who has that job); certain things may be open/unknown and subject to discovery or even creation as part of in-play procedures. A given game presents its own profile for them.

Another issue is a matter of who does it (any of these). Your phrasing suggests a very strong swerve toward a GM taking on that job.

OK, rather than mix up the concepts, let’s take a very solid and simple case, with Sorcerer. It fits the first phrasing above, with unknowns to be filled in as part of preparation, and also, that this is a GM job. Very much not like Cold Soldier, the other end of that spectrum. The player conceives of a great deal: the concept for the starting demon, and the Kicker, to name a couple of things which are usually the GM’s job in other games. However, then, it is definitely the GM’s authority to play those things, including further content for each, any part of which may or may not be known to the player. Once created and handed over, i.e., in play, the player doesn’t “say” anything about what they’re like or what they do.

What I want to know is, do you associate this profile for a given game to indicate as well a particular sequence of play, a particular planned reveal, a particular conflict which play drives toward? Does it imply, to you, the sense that play is supposed to “go this way” and would be messed up or even ruined if it did not? Does preparation seem to you to be the same thing as maintaining direction and control, or at the very least, monitoring how much fun everyone is having and nudging content as needed?

I ask this because I have been battling for a long time – perhaps 15 years – against the misconception that a rather solid, extensive profile of fixed information, known to someone, if not everyone, is the same thing as story-control by that same someone.

I just wanted to note a couple of things about this game: Ron’s notes about backstory are spot-on. Our after-play reflection opened up new avenues in my thoughts about this game, and I highly recommend watching them if you haven’t yet.

I’ve played Cold Soldier quite a bit, but this was one of my best sessions with it. In the past, my play of the Dark Master has been very algorithmic: “Issue command. Narrate adversity. Issue next command. Repeat.” This will produce thematically focused fiction, and it will (potentially) provide a context for the Soldier to do something interesting. But it is perilously widget-y. This session, I brought what I’ve learned about successful play over the past year and made two creative decisions that were very effective: (1) I brought the Dark Master’s social context into play as much as possible (her relationships with Hades, her emergent rivalry with Athena, etc.) (2) I hammered the negative blowback of her actions as hard as possible, up to the point of burning her immortality. Taken together, these choices made the Nymph a rich, situated character to play.

Finally, on the of sympathy for the Dark Master, I’ll note that in this game I drew on what I know of spousal abuse, particularly abuse perpetrated by women against men, from loved ones who have survived it and survived its aftermath. Drawing on this highly vulnerable material made playing the Dark Master a very meaningful experience for me. I’m still processing this.