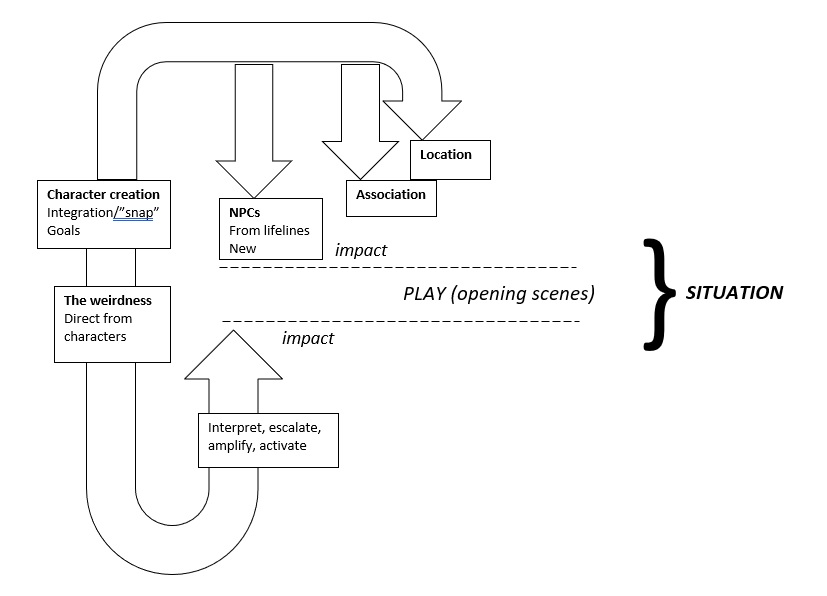

Working from the presentation and discussion at Situation: primary and primal, and drawing upon the game shared in Here comes trouble, now I want to show you exactly what I mean by scene framing, resolution (both successes and failures), and those weird black arrows in that circle diagram. I’m using our short game of “Whimsical Ways,” which is my hack of Legendary Lives, played by me, Helma, and Noah for four sessions.

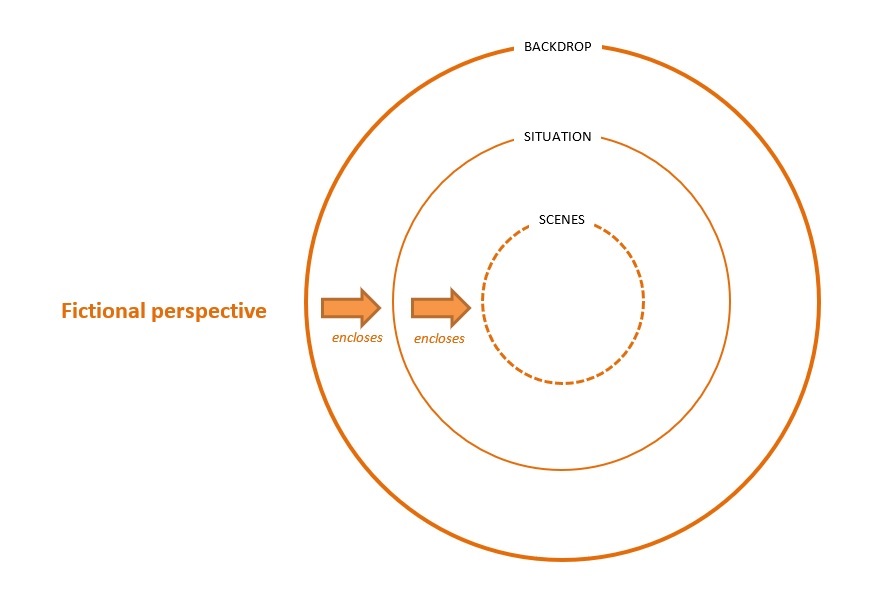

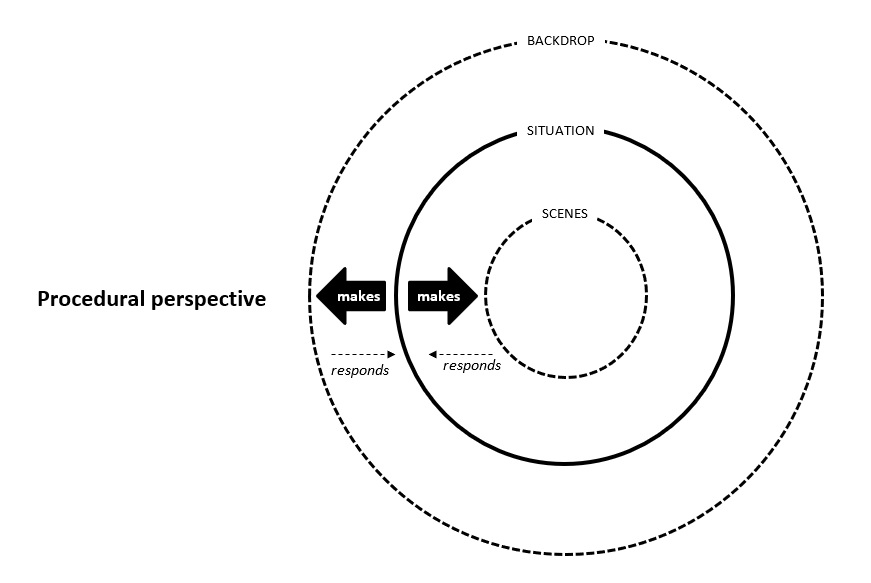

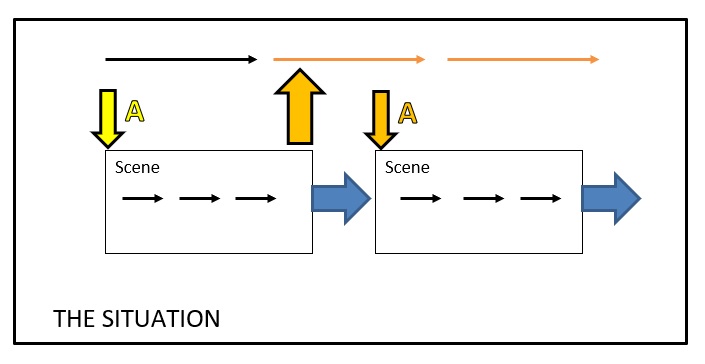

I’ve included the orange and black diagrams I used before, the new “box” diagrams I describe in the starting video here, and a funny-looking thing I drew to summarize preparation for Whimsical Ways. This is a very visual-aid type presentation so just listening isn’t going to be enough, and you’ll need these images because they might not be ideally visible on your screen.

Here is the point: I am talking about play in which the outcomes, situational effects, and purposes of scenes (i.e., events during play) are not canned and programmed. The mystery may or may not be solved. The adventurers may or may not survive. The relationship may or may not reconcile. The very point, genre, mood, “story,” and experience are all non-guaranteed, whether in some specific form or in general.

I stress as I have so often done that this idea has nothing to do with whether and how the authorities of play are concentrated or how they may or may not shift about among persons. It also has nothing to do with when a given event or feature of play is invented, i.e., during play or beforehand. To be especially clear, I hope, I am talking about play which does produce fiction (sequential events, blah blah blah) but is not either pre-written or reliant upon intuitive continuity (for which, see Monday Lab: intuitive continuity continued, and if you do, please review the videos linked in the text of that post).

As of this writing, I have only finished the introductory video and I’m still working on the sequential account through our four sessions. The latter is where the real examples and proof-of-concept are, so I know some of you will be yearning for it before long; I’m working on it right now. But I want it to be good, which means doing a shoot, then watching it all the way through, then doing another one, and other tricky stuff.

33 responses to “Situation: case study”

Part 2! concerning session #1

Here's the direct link, and I've altered the original link to go to the beginning of the (now existing) playlist.

There are a couple of little bits that I missed mentioning, so I'll list them here and follow up with a bit more about them in the next video.

Part 3! concerning session 2

For this part, I focus hard on the little black arrows inside the scene box. What are they? How do they "go?" Is there a "where" they go to? What do dice have to do with it, for this game?

Here's the direct link into the playtest, if you've caught up with the previous ones.

Also some reflections about playful play as a method, or rather, the method, for game design.

Evolving situations.

I've been wondering about something watching these videos and trying to understand the procedure that leads to the creation of the situation, particularly focusing on the discussion of the diagram in the first video (from 12.00 onwards more or less).

It's particularly evident here because of how character creation headstarts the situation, but I think all discussions about Legendary Lives and our own Discovering Dusters game may be relevant too.

It is my impression that this type of process leads to a situation that is strictly tied to a location, not only because there's enough detail in the characters' past and present to require a context (a profession, a family, enemies, loved ones), but because it leads to the creation of a cast of relevant non-player characters and background conflicts and whatnot. In our Duster game the process was probably reversed (situation came first) but I think the result was similar.

It's clear that the situations created are solid and ripe for interactions. My question is: what happens when characters move over? We go over the same process again? We keep playing in the same area and context? We use play procedures that take everything that happened and the fallout of the players' actions to start a new situation-creating context? We start over with new characters?

Don't take this as criticism, I'm just expression some of the questions I have about my own attempts at this.

Nope! No way am I letting you

Nope! No way am I letting you escape up into the high-level large-scale what-about land. You stay down here with me inside a scene inside a situation, and we aren't leaving until all the processes and methods are exposed and discussed.

In fact, this whole presentation is about only two of the circles in the black diagram: situation and scenes. It happened not to interact with backdrop particularly, even at one point when it might have. So after this, we will find another game to examine in which backdrop is much more engaged via its arrows with situation, or rather, situation's arrows with it.

Therefore I'm not going from situation to another situation until everything about that black diagram has been demonstrated and understood via looking at play.

I’ll say one thing so it’s

I'll say one thing so it's clear that I do take your question seriously. There are many, many ways – arguably fractal-style infinite – to arrive at situation, "big situation," for purposes of role-playing.

Let's take the subset that relies on text, i.e., the book, the canonical setting. Even there it can occur in completely opposite ways: to provide backdrop and say, "hey, figure out any situation you think works in some spot in this backdrop," or to to provide a highly specific and detailed situation and say, "play this."

Or we can look at it in terms of expected change. Some ways presuppose characters who by definition can and will travel from situation to situation. Others presuppose a context in which the starting situation will necessarily become situation-prime, then situation double-prime, et cetera, through the course of play. Other ways presuppose a developmental process, for characters, which necessarily means the way they interact with any circumstances will differ in the future, therefore creating new situations.

Or we can look at it in terms of characters and preparation process. Here, in Whimsical Ways, it's admittedly solipsistic: just because we have these player-characters, this is the starting situation, and here's a method to use toward that end. That method will be somewhat altered for later situations, and I do have a method for that too, but the principle is still in place. It's similar to any serial fiction that purports to be "about" these characters; somehow, whatever situation they're in, it's relevant to them in some way, minor or major, direct or indirect. Whereas in some other games, the situation, as a created fictional thing, is deeply uninterested in these characters, and the juxtaposition between what is happening there and what they bring or who they are, yields a primary (productive) uncertainty for play.

Do you see what I mean? Our discussion of scenes, situation, and backdrop may occur for any of these, and whichever one it is (and my summary above is a pitifully tiny fraction of the possibilities), it will necessitate its own ways and means of arriving at "the next" situation, including the possibility of explicitly saying there isn't one.

All of the above assumes a working system for arriving at a situation in or for play, whether textual or personally-derived doesn't matter. The frightening and – it must be said – overwhelmingly stupid, vast array of non-working practices, necessitating a great deal of compensation, denial, and reduced expectations in the experience, is not what I'm talking about.

Part 4! concerning session 3

This session contained the only distinctly hard scene cut in the game, so I talk a lot about momentum along the little black arrows inside the scenes, and how such cuts evolve, or however you want to describe their emergence, appearance, or application.

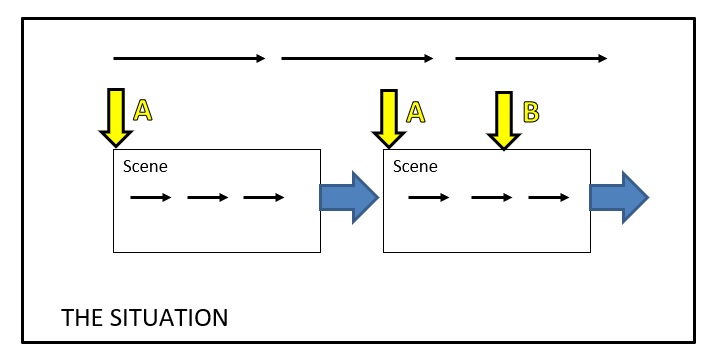

I would like you to note how I'm checking into the situation all along, or at least at any point in which I am not directly focused right between some character's ears. I definitely always have to do it for an A arrow, at the start of any scene, but here I'm talking about checking "up" in order to see if there's a B arrow heading in, i.e.,, during the scene we're playing rather than at its beginning.

Here's the direct link.

Is it different from a players point of view?

No, or at least, not in my experience. If you want to be picky, a players situational awareness is different from the Situation the GM knows, but it is a part of that and everything else, the little boxes and arrows, ia the same. I tried to mess with one of Ron's diagrams to illustrate my point.

Because of the above, I prepare for a session pretty much like I guess a GM would do. I check how the Situation may have changed (the part of it I'm aware of) because of what happened during previous Scenes (the thick golden arrows) . The I look at if and how that would influence my characters views and reactions to what is going on. This includes for example thinking about their relationship to and opinions about the PC and NPC they have encountered so far and why and how those may have changed. All of this makes it easier to know how the character would (re)act during the Scenes.

Please keep in mind that my situational awareness as a player differs from my characters which can lead to interesting situations at the table.

Especially if my character is in a Scene and I halfway into it realize I have lost my bearin but don't want to stop play for that. A good example for this is the whole scene when Shkazzak (the guy) shows Thirteen the meatfarm. In that moment I'm feeling somewhat fuzzy when it comes to the details of Thirteens religion (though sure about how they were feeling about it) in other words Thirteens situational awareness covered a “bigger area” than mine (the details of their religion, part of their backstory). In that case I felt comfortable to continue play because I knew what picture they had of Skazzak and that this would guide their reactions. This led to a (as far as I'm concerned) both memorable and fun to play dialog between Thirteen and Skazzak.

Normally though it would be the other way around, like illustrated in Thirteens encounters with Oggox, they were from a very simple premise, Theoxxa was in love with Oggox and Oggox loved Theoxxa too. Leading to them telling Oggox they hade the same goal: “happy Shkazza couple with robot gone” as well as to their later decision whom to kill and whom to let live. Sometimes though I can get a little bit stubborn, like when “arrow B” hits in our third session and I tell the GM: no, my character does not recognize that the sword in Fours hand (the robot-likeness of Theoxxa) isn't Theoxxas, since the brawl on the Temple-steps they had the distinct impression Theoxxa did put it some place and simply left it there. But that opens a whole different can of worms that I don't think should wiggle around here.

So, to conclude, during sessions I as a player have a good enough grip on the situation the scenes we are going to play are embedded in. Me deciding how to play my PC does not differ from how the GM will make decisions about playing the NPC. Even if we have “hard” scene transitions I can easily enough orientate myself to know what my character would do and say and I know that how the Scenes progress and what happens in them has the potential to change the Situation. Which makes me really happy.

You are entirely right! All

You are entirely right! All the arrows are experienced and utilized by real people in terms of each person’s particular instrumentation. Those terms GM and player make a lot of sense when considered as different arrangements of authorities toward the developing fiction, for which one’s presence as a person isn’t different from anyone else’s.

I suggest that all your excellent points about one’s necessarily limited knowledge of the situation applies to a GM as well, because they obviously cannot know what the player-characters will do, and those player-characters are as fundamental to the situation as anything else, and in many cases more so. That’s why, for example, I completely deferred to your judgment about Thirteen’s perception of the other robot’s sword.

Even better: you mentioned that internally, a person contrasts their own knowledge of the situation with the fictional knowledge held by the fictional player-character, which is a feature of play at all times – and I suggest that this applies to a GM as well, for everything and anything they may be responsible for playing. So I’m saying, not only “yes,” but double-yes and triple-yes.

I delayed responding to your comment because it makes most sense with the sixth part in mind, in which these terms are instead conceived as [guide, screenwriter, and director] versus [call-and-response audience]. When this happens, then the players are almost destined to interfere and disturb “the story,” in any aspect of its content, atmosphere, pacing, and intended emotional effect, even if they try not to. Therefore I chose the word versus very precisely, above. The relationship among persons at the table becomes intrinsically creatively antagonistic, thus, according to this view, it must either be firmly controlled – to the extent that who the players are literally does not matter even a tiny bit – or papered over with a compensations, e.g., fake cheerfulness, broad hints, and extravagant explicit agreements.

Part 5! concerning session 4

I tried to punch the point pretty hard for this one, which takes us through the end of our heroes' adventure in the shkazza mountain encampment. Here's the direct link.

One supporting topic which I thought about just after finishing the recording is the contingency during play regarding the "rogue doubles" characters. I don't think I had my thoughts together enough about them at the very beginning of play, but at any point from the start of the second session onwards, the player-characters might have run into them much more explicitly, or learned much more about their presence and activities.

This is a more extreme version of the point I made about the fourth session in isolation, in which some of the moments of the first half-hour of play could well have led to (any one of) very different set of confrontations in a very different micro-location of the situation. Given some different stated actions, some different dialogues, and some different outcomes, arguably our entire adventure would have been "about" something else entirely.

Hopping up?

Hi Ron, I very much appreciate these videos, they're exactly the kind of thing I was asking for in the situation: primal/primary comment. I've been trying to play this way for a while now, thanks to Adept Play, and this work gives me more vocabulary and a better conceptual model to understand what's going on.

Regarding your very last point made in part 5, where you mention what you want to talk about, I admit to not following it. I get the idea that planning decision points, encounters, etc. in advance is problematic and why, and that situation with various techniques and procedures is powerful and more than good enough.

But at the end you say, "Everyone keeps avoiding getting down there in the black arrows with me, playing through what is occurring in the context of the known – different people at the table having different knowns, and that is ok – and not hopping up. Certainly not hopping ahead. That's what we need to talk about." I'm confused about what you're getting at here. Can you explain further?

“Hopping up” here means

"Hopping up" here means examining what the situation is while playing a scene. One is checking an A arrow's content or whether a B arrow is incoming.

Or, from the next diagram, whether a big gold arrow is punching out of the scene to change the larger situation.

All of these are good things but they can be addictive either to do or to talk about, and in play they can slide into certain behaviors I'll be presenting in the final part of this series. I've also noticed that many of the people involved in this conversation want to talk about them very much.

Whereas I'm encouraging more attention to the black arrows inside the scene boxes, and the experience of playing them with enthusiasm and ongoing attention. Imagine with me, for a moment, playing characters and environmental features and any number of occurrences in a scene with all situational context and influences accounted for. Whoever has the job of bringing in or playing or confirming any of those things, one or more persons, is doing it. There is no difficulty; everyone is doing what they need to do so that interactions, movement, stated actions, and anything else actually occurs.

And we don't end the scene. We keep playing the next "little now" after every interaction or event. The point is that more black arrows proceed from where we are, inside this same scene. That's what I'd like to examine, because that seems to me to be in peril of becoming a lost art.

Hi, I was exactly wondering

Hi, I was exactly wondering about those black lines inside a scene. I would love to see more attention to that. I would have a tendancy to close a scene after a little black line – if I understand it well?

In Trollbabe for instance, is that what is happening (a scene is only one black line)?

Or, is more like Sorcerer, where you could have two bangs in the same scenes for unrelated reasons – because I don't know, an big golden arrow comes from the situation right now.

All of this would need an example, but I'm delighteted to see it's not finished!

?

?

Trollbabe's rules do not limit a scene to a single conflict. If there is one, there may be two, or five, or ten. A scene is not mandated to end simply because a conflict has been resolved. The diagram that demonstrates how scenes and conflicts relate to pivot points includes an example of a scene with more than one conflict.

Regarding black arrows doing

Regarding black arrows doing what they do, without much change to or from the overall situation as we know it at the moment, here's a good example from a few years ago. This link goes to a comment in one of the "Sorcerer Musik" game posts, which itself links to sessions 2 and 3. At that time I didn't understand YouTube playlists and was still figuring out all sorts of other infrastructure, so you'll have to use the links directly; they don't run sequentially via YouTube itself.

If you want, please watch the last twelve or fifteen minutes of session 2, which is a fairly intensive scene cut including lots of assertive situational content resulting from events earlier in play. You'll need to see that material in order to know what's going on, but the action I'm referencing, however, takes place in session 3.

OK so to get into the nitty

OK so to get into the nitty-gritty of scenes and their black arrows, I’d like to describe a situation from my last D&D campaign. This is the campaign I mentioned in a previous post on the site, *A Game of D&D* I think I called it. Anyway, the backdrop is the world is ruled by a cruel and decadent elven empire, where humans are enslaved, and evil creatures from beyond are trying to invade but the empire is too incompetent to recognize or deal with the problem. In this particular game session, an undead plague has been unleashed on a city where the player characters are trying to stage a rebellion. In the last session, one of the party members had been captured, and the rest of the party managed to rescue him from the dungeon below the autarch's citadel. As the group reaches the ground floor and races towards the exit, they see the guards at the main entrance to the tower quickly shutting and barring the doors, as a massive horde of undead rushes towards them.

Now, this particular session begins. The main doors shudder under the assault from outside. The guards look at the party, the party looks at the guards, and then they check the stairs leading to the next floor of the tower. A contingent of imperial guards and their commander is on the stairs, and they stop in their tracks, the elves and the party eyeing each other, waiting for someone to make a move. As they do, they hear the sound of wood splintering from the main doors, accompanied by the hungry howls of the undead.

Now from my point of view, I know that most imperial troops are lazy; they are used to beating up and capturing escaped slaves, and some of them even have experience putting down riots, but fighting undead is something new and frightening to all of them. On the one hand, their instinct is to descend upon the rebellious humans and put them in chains, but the presence of the howling undead has them confused and uncertain. The Elvish commander, because she is serving the autarch of the city, is going to be one of the most competent of her profession. She knows her primary duty is to keep the ruler safe, and to help her escape. In her mind, a few escaped humans is of little consequence compared to the danger of the undead to her liege. At the same time, she is sure to share the common prejudices most elves have towards humans, namely that they are unreliable, savage, and little better than non-sentient animals. So, she too is uncertain about what to do.

The same can be said of my players. They argue with each other, some of them wanting to just make for the main door, let the undead in, and then try to cut their way through while the undead take care of the elves. The other half of the party want to negotiate with the elves, seeing as the undead are a threat to them both. They decide to try to negotiate.

The sorcerer yells up at the Elvish commander, insisting that they let them through or he’ll burn them up with his magic. I call for an intimidate roll, which he flubs. I consider how the Elvish commander would react, and since she has spells of her own, including a crystal she can activate to create an anti-magic field, I have her laugh out loud at the upstart human. Chuckles ripple through her squad of troops. At this point, the human bard steps in. She basically makes an impassioned plea that despite their differences, at least they’re all still alive, while those outside are not. She offers to fight with the elves, reasoning that with their combined strength the commander will be better able to defend her liege lord; in return, the bard asks for a guarantee they will not be apprehended. Since this is exactly the kind of thing the Elvish commander wanted to hear, but because of her prejudices I'm not sure how she'll react, I ask the player to make a persuasion check but I give her advantage on the roll. She rolls well, and I have the Elvish commander agree, but says she can’t guarantee the actions of other elvish officers. An understanding having been reached, she orders her troops to make room for the party.

They’re just getting into place when the doors finally give way, and the undead stream in, moaning for flesh.

Now one question I have is, is this still the same scene? I haven’t had to check the backdrop or the overall situation at all yet, I’ve just been making use of the elements that were already present, such as the goals and desires of the elves and the undead. On the other hand, when the undead burst in, things change dramatically. Is this change sufficient to consider at a new scene?

Anyway, what happens next is the sorcerer puts up a wall of fire at the foot of the stairs, while everyone backs up, weapons ready. The Elvish commander sends runners up the stairs to keep everyone else in the tower apprised of the situation. The undead storm in, rushing through the wall of fire and reaching for the living characters. One of the players glances at the sorcerer player with a look of outrage, and says “first there were zombies coming for us. Now, there’s zombies on fire coming for us. Thanks a lot!" Now to be fair to the sorcerer, the wall of fire did vaporize a fair number of zombies, but it was still a funny line anyway. The flaming zombies team up, grappling Elvish troops and bringing them down, and getting a few munches on the PCs too. They have a running fight up the stairs, and although they destroy a fair number of zombies, the sheer number of the undead is very hard to deal with.

At the next floor landing, the party is looking around for a means of escape. They see an open room with a balcony, and so, waving goodbye to the elves, they run into the room, slam the door shut and bar it, as zombies pound on it from the outside. The players run to the balcony and look around, trying to determine if they can jump out or otherwise escape by that route.

Now at this point, I do have to look at the larger situation. The players are asking if there’s any undead on the street below, and to answer that I have to consult my knowledge of what’s happening in the city, and how many zombies have been attracted to this tower as opposed to other locations. When I do this, I tell the players there’s quite a few zombies on the street below, but a couple of blocks away the streets are much clearer. The players then hatch a plan to escape via dimension door to a nearby rooftop, and then climb down that building. From there, they will try to make it to the docks, where the rebels are commandeering ships and using them to evacuate the population.

As I think about this example, I’m wondering if there’s an objective way to tell where exactly a scene ends, or whether there is a lot of flexibility to it; maybe it’s a fuzzy concept. When the game session started, there were two main issues: a swarm of undead were trying to break in and eat everyone; Elvish troops were confronting the characters, and under normal circumstances would try to capture or kill them. I could see someone saying the negotiation with the Elvish commander was one scene; the fight up the stairs another scene; and trying to escape out the balcony yet another scene. In that case, I did not consult the overall situation until the third scene. On the other hand, there was a larger overall problem, namely the players wanted to escape from this tower, and all their actions were directed at this issue, so were they really separate scenes?

Regardless, as DM I had a lot of fun here, playing the elves being so out of their depth was cool, and the horde of flaming zombies was genuinely terrifying. I really had no idea what was going to happen, and it was suspenseful pretty much the entire time.

Anyway, I look forward to any thoughts or analysis you all have about this example.

I think I have good news

I think I have good news about the question you raised and returned to, about whether any given point of play is a new scene: that I have no way or interest in finding the single conceptual cut-off point which applies in all cases. If at least half a millennium of creative work and critique hasn't come up with one, I don't think it's my job to do it.

The value in your post for me is that your group's black arrows did continue through a series of played and resolved-when-necessary events. There were a lot of known and active elements, all sorts of characters with stuff to do and doing it, with multiple consequences that couldn't be taken back, and you all kept playing it through with little or no shift/break in the fictional events. You didn't do what I'm criticizing in that discussion, which is to dodge to a scene shift just because one thing happened, and often to abandon play of the ongoing fiction entirely. That's what the whole black-arrows concept is talking about and we should discuss that.

If there isn't a discontinuous "bit" in fictional time (in other media I'd say "presentation," which doesn't quite work here), then I don't think it matters much to nail down a precise yes/no. Big things can happen in the middle of a scene, much as you describe in terms of violence and breaking a barrier, or new information can change-up all the relationships, or whatever.

If something like that happens, then we could go all metaphysical and literary, asking, is that really just a black arrow, or is it a blue arrow with a minor new "A" arrow which does its job but doesn't change anything? But I say no to the rabbit hole. Without some solid signal otherwise, then I really do not think anything important resides in dissecting whether this is a "real" scene-shift or a big event inside one.

If there's some procedural need to call it a closed scene vs. an ongoing one, e.g., regarding game mechanics, and if there's any question about it, then whoever has authority over the transition applies that authority, which is, after all, their job. When that's me, I'm inclined to look for changes in kind, and in how we look at it, rather than in degree or the content of ongoing events. But that inclination is not a definition and I sense the rabbit hole beckoning us with ever-more tempting gestures. My last three paragraphs all started with "if" and I've deleted about four nuance-y footnotes of my own. Let's really say no to it.

P.S. Let’s take play-examples

P.S. Let's take play-examples into their own Actual Play posts. I almost asked you to re-post it there but decided not to, because it was continuous with your original comment. From now on, though, I think we should branch into dedicated discussions for applications and examples.

Part 6! how not actually to play

Here’s the final part of my planned series. More may be added depending on how this discussion proceeds. It concerns doing something which is, however harsh this may sound, not identifiable as play, as its primary feature is the negation and constant repurposing of what others are saying and doing. At one point I contrast it with "legitimate" play – and this is not a slip of the tongue or unconscious tell. I mean it.

Here are some things I planned to include but forgot, or didn’t emphasize enough with phrases I wanted to use. They won’t make any sense unless you watch the video.

Players have to “do,” providing basic kinetics with black arrows, but a backwards green arrow always reinterprets (directs, redirects, restates, ignores) them so that the actual events, “what happens” which affects the situation, are purple. Depending on how the green arrows are actually employed, the black-arrow activity turns into Brownian motion, meaning it does little or nothing; or it retroactively seems quite directed if you accept that the purple arrows are what they really or ultimately do.

A purple arrow is either super fixed and known ahead of time, or improvised “to be interesting” or “to be what they’re looking for.” However, the latter, once improvised, is equally super fixed and known as the former, in terms of how play relates to it. In other words, the only difference is how long “ahead of time” is, with no difference in kind or effect between a lot of time before play begins and a little bit of time during play.

The controlling person (or persons, if there are several, or everyone) swears they’re only guiding, letting the other people do what they want, indicating the black arrows. In many cases they seem to believe it, in which case the magical words atmosphere and tension are their perceived functions – this is related to the “radio voice” that I mentioned, which is effectively the ongoing expression of the purple arrows, i.e., “the story.”

When I point directly to overriding or ignoring what was believed to be genuine input or invocation of game mechanics, they claim they would never do such things if the players would only do the right things (genre-faithful, “obvious,” there are many adjectives to use here). The same applies to dice or other instruments – they wouldn’t override or distort what these instruments did if the damn things would only “roll right” or wouldn’t “ruin things.”

They also interpret play as I’ve described for Whimsical Ways as some sort of particular mastery at jimmying the purple arrows into place. For example, the destruction of the pyramid and the fates of Oggox and Shkazzak would be interpreted as conceived and known well ahead of many of the rolls and outcomes which in reality brought those things into resolved form. They interpret the interactions among the players and GM in a game like that one as a competitive Ouija Board manipulation, with everyone pretending they aren’t “doing anything” but actually green-arrowing everyone else.

I planned to include this

I planned to include this little fellow in the above comment, so here it is, from page 40 in Väsen, in the Skill Tests section.

This video is great,

This video is great, shockingly accurate etc. Well, I remember that about a year ago or so, I posted to the discord in a state of genuine shock and with feelings of despair after playing a session that your video described perfectly. My character was killed (without a roll) for going off the rails. And wow…your point about the forced naturalism rather than hard framing seems so specific that its hard to believe how broadly it applies. I've stated it already, but the feelings I felt were hard to come to terms with, and actually kept me up that night!

I need to write a funny story here now, that I just remembered today. My friend who ran that game I mentioned above (I like her a lot, will never play with her again) played in a little game of The Pool with me and two of my best friends about a month after that fiasco. While the other players were actively pursuing interesting goals of their own, she rode into a town and went to a tavern, in a desperate search for a mission. She actually asked me where the nearest tavern was, and when that didn't really offer up anything, she started asking random miners what was "going on" in town. She started pulling random pedestrians off the street and asking them "who was in charge". Meanwhile, some stuff was clearly happening in town, and indeed, in other nearby places. But I never told her what to do, so she was stuck desperately searching for a purple arrow!

Again, I point to podcast "play", in which what you are describing happens universally (as far as I can tell), as possibly the cause of this style of play in younger/new gamers. And I would like to point out that in the podcasting/entertainment environment it happens consensually–indeed, the players help the GM out because they need to guarantee a story that sells, above all, and they have no time to really play, because to do so would mean to risk everything. Real play is always practice, and you don't get redoes. Even though the not-playing is subtle and agreed upon, it is visible enough that the only players ever credited with being geniuses at playing are the GMs, and audience members who have never really played are just as aware of this as anyone else. Sure, that player might have a nice voice, and wow! they really sold that intimate scene of personal strife…but the GM is bringing together the Story.

The two players I have played with who were introduced to roleplaying through podcasts are the only two players I have ever observed this behavior in — specifically, the need for a purple arrow. I will note for a final time that many seemingly new players have listened to tens or hundreds of hours of this kind of play, and they are, unfortunately, learning by listening.

I recognize what you’re

I recognize what you're describing regarding playing characters as if they were commandos or ninjas on a black op, with bizarre results when the played situation is rather naturalistic and without stress. It showed up a lot during the development of Circle of Hands, in which someone would sneak along behind the barrels or take to the rooftops, or swerve to follow and shadow an incidental character which the GM had unwisely described with a bit too much detail, thus perceived as "this person is important." More recently, more than one person encountering Sorcerer via play presented at this website has struggled through a phase of seeking signals for what to do, and feeling blocked because they were not in fact blocked or directed.

I think it's good to recognize when a person is doing this out of pure training but is stating that they want to do something differently even if they don't have the words. In this case, since many role-players try to solve their own issues by GMing (i.e., control, as they see it), having them to play characters instead is the way to go, and to be ready for plenty of repetitions which will feel unsuccessful to them, except in retrospect. But it's equally important to recognize when a person has no desire to play differently and is merely frustrated by your presence, which they perceive as uncooperative, defiant, or even unskilled. Your example to remain friends but simply not to play with them is the only viable response that I can see – and I've tried many others, none of them good no matter how "nice."

The *gasp* X-card

I want to talk about the X-card here. I have been sitting on some thoughts on the X-card which are uncompromising and full of genuine wrath (related more to the fetishization of safety and the silencing of people/dehumanization of people for whom safety tools are quite important), and I think some of them relate surprisingly well to the final video in your series. I might be bad at getting this down in writing at first, but I don't have much time, so I'm going to give it my best shot (every one of my posts comes with a free apology, apparently…).

The use of the X-card to cut content, not because someone is crossing a line/a person wants to veils something, but because the player simply doesn't like it, seems to me like a technique for the distribution of backwards green arrow usage. I don't know if/where the purple arrow comes in in this context, but I do know that the use of the X-card in this way is often excused using ideas like maintaining the flow of the story, maintaining genre or tone, which lines up quite well with the reasons you described for their use in your video. If I'm understanding the different arrows and interactions incorrectly let me know.

I haven’t written or raised

I haven't written or raised the topic of the X-card very much because – for whatever reason – I've only rarely seen them. I think the only one I've seen, as in, a real physical item, is at play-tables set up at a con, i.e., mandated to be present, and although I played there all day, no one used it despite some pretty raw content in at least one session. I've played in online games where it's claimed to be present, for example at the Gauntlet, but again, there was no sign of it in play.

I don't regard it highly specifically as a safety instrument, as discussed in Conversation: Safe Spaces and as examined through several Italian games (Stonewall, Little Katy's Tea Party), so our views are likely to overlap about that.

But here, you've raised something I haven't considered, which is using the X-card in play-situations where emotional or psychological safety clearly isn't at risk. As you've described it, yes, that's clearly a green-arrow technique, but I'm surprised anyone would do it. That would be really obvious, and about forty years of role-playing text and training have provided (slightly) more subtle methods which preserve the elitist rhetoric of "the story" and the illusory agency granted by intuitive continuity. The text from Väsen is pretty direct about that.

For example, drawn from my dozens if not hundreds of relevant experiences: to "forget" the dice or any resolution-instrument for players who do things too unpredictably or too directly to the point or too "delay of game" in terms of the planned events. It’s simple: the GM doesn't call for rolls no matter what they do. It’s particularly pointed when the player’s character talks to other characters in an inspiring way, they ask good questions, they try to hit something – anything that calls for a roll then receives no roll. The player finds themself speaking into the empty air.

Since this and similar passive-aggressive techniques maintain a pleasant illusion of "the story" and "flow" (for everyone except the target), they are widely taught. So if people are using the comparatively pipe-wrench-like X-card for green-arrow purposes, then … geez. I want to know more about your or anyone's experiences in which someone was OK with being so crude.

H'm – moving as far into speculation as I care to go – I am thinking about the fact that a great deal of so-called storygaming play is not different from single-GM story control at all, but simply distributes exactly these same control techniques around the table. In other words, everyone green-arrows everyone and competes over which purple arrow will occur next. The one-on-one "fuck you, no" quality is touted as some kind of creative power or (somehow) story-ness, exerted by anyone upon anyone, all the time. In this case, the very abusiveness or blatant technique would be a display of power, and its alleged safety-ness or good-ness is the thin social cover for doing so.

Maybe I shouldn’t talk about

Maybe I shouldn't talk about things I haven't experienced firsthand, because I have also noticed that even when the X-card is present, it seems to never get used. My post was talking about online chatter I have seen in other places about how people (supposedly) use the X-card to maintain the feeling of the game by cutting content.

I'm now realizing that I'm having a hard time finding some of the original discussions, but I would point to the recommended techniques in every X-card related document I have seen, which is to use it very very often for trivial things, to use it all the time. I took this at face value when rereading the documents recently, and along with examples given in the original X-card document (about cutting content that is not fitting with the genre, rather than content that is crossing a line), I took this at face value as what real people were doing…

The thing is, your post is making me reflect a bit, and making me realize how different the actual usage of it at the average table is from the suggested/supposed uses people claim to be doing online. All that the presence of the X-card seems to really do is make people play timidly, because the only means of communication it allows is a complete stop. I'll stop speculating and go back to real experiences I have had!

Hunkering down

This video series is illuminating, particularly in the context of all the discussion that fed into it. Helma, your comment "Is it any different from a player's point of view" is the final puzzle-piece I needed to express exactly how a GM is "just another player." I directed my duet buddy to this series and that comment in particular (we play our first session of the NEW RQG game in a couple of days!), and he found it really helpful as he gears up to play.

Ron, in regards to staying with the black arrows, I thought about the last few paragraphs of this RQG actual play report. This was a somewhat new experience of play for me, because I so often find myself inspired by 'hopping up' and looking at the larger landscape of the fiction. In this moment, the characters, factions and locations, having been 'actualized' in scenes, were laid out in front of us. I knew there were some big golden arrows on the periphery that I'd have to worry about at some point, but even between sessions I was only interested in the black arrows.

I was also thinking about

I was also thinking about your RQG game, and how moment to moment, sometimes conversation to conversation play proceeded for a while within scenes.

But …

… the example you provided doesn't work for me, because it's about speculation or expectation for later play, not play that actually happened. I think there are several possible examples from the sessions you did play. Can you identify one which might be particularly suited to the concept of black arrows within a scene?

It’s a good point. To answer

It's a good point. To answer your question better, I'd point to Session 4 as an important pivot. It forced me to practice non-attachment to the golden arrows. Looking at it from this vantage point, I'd say we were learning to trust the black arrows, to let events unfold within scenes. Even the arrows that moved us between scenes were primarily black – the obvious consequences of actions, rolls and statements directly before.

Play seemed in the moment (but not in retrospect) less focused and obviously cohesive. And I think this is connected to the conversation you and I had in the comments then, about becoming comfortable with seeing what happens, even if on the surface what happens is not much:

Even though I was careful to honor my characters and avoid "sending in the ninjas" before session 4, I still reached for the golden arrows first when asking "OK, what's next?"

After this session, we shifted to a more hunkered-down posture of play. I did far less "glancing up" from that session through the end of the arc. There are a couple of black arrows that originated in this session and ran continuously to our final session of the game (for instance the CHA v CHA resistance roll that established Narmeed as a genuine representative of the Storm Bull to Willandring and Petrada).

To point to another example, I'd say that sessions 7-10 were like a marathon of black arrows. I 'hopped up' when I absolutely had to ("OK, the Hero Band has traveled this far into the Troll Woods – who/what is here?" or "The Wasp-Riders have spotted them! How do they appear to them? Who would they send?"). However, I ducked back down into scenes as quickly as I could, and we played these sessions very hunkered down, absorbed by the immediate events.

As far as play goes, that’s a

As far as play goes, that's a big yes. However, I'd like clarify my taxonomy because I can see it mutating, and I can foresee content vaporizing with one or two more replies across one or two more people.

A yellow/gold arrow is not necessarily "change." If a scene starts and whatever eyeblink of cognition it takes to remember that you are playing on a big spaceship, not just this cabin, and not suddenly across the galaxy, that's still an "A" gold arrow. It feels like nothing. You did do it, and believe me, you said it in some way even if it doesn't seem important and was instantly passed through.

Even a "B" gold arrow may not introduce as much change as one may suppose by looking at its big visual glory on the diagram; its only real definition is an increased or additional component of the situation which wasn't in the scene before.

A blue arrow is a scene transition: any discontinuity, however slight, in time or space; possibly a significant change-up in composition qualifies too. You will notice, I hope, that the transition in tracking time from "combat rounds" to "turns" or any other bigger unit often qualifies as a formal version. It's represented as an arrow forward to show that the previous scene is acknowledged to have happened as a fictional constraint, as opposed to a green backwards arrow which basically retcons what's been played into the new scene.

When you say a scene transition is "just more black arrows," I want you to say instead, "we played the blue arrow with little or no new input coming in with the gold A arrow, staying pretty much in the known context and highly constrained ['motivated' 'driven' whatever] by the previous black arrows' content."

Also, going back to older points, when I say "scene," it refers to the ordinary, usual, and universal phenomenon of any fiction, not the specifically theatrical specification, and not to verbal or procedures in role-playing. In other words, role-playing always has scenes, almost all of it more than one, and therefore almost all of it has scene transitions. There is no need to speak of these transitions as if they have to be formally acknowledged or to use any special ritual or instrument. Some rules-sets do that, that's not a big deal, and it's not relevant here.

Got it. I wanted to hold off

Got it. I wanted to hold off on replying until I'd had a chance to review the videos. I didn't come away with any glaring questions, and your note on accurate use of the terminology makes a lot of sense.

Reflections and comments

Let me preface this by saying that I feel like there is nothing to add or critique in terms of how you constructed the analysis, and the resulting vocabulary: as far as I can see, this works and feels like a perfectly functional foundation for all further discussions on the subject. I have nothing to add about the theoretical aspects.

Moving into real life examples and reflections on those, there's a few things I noticed.

The way the situations are described in the videos seems (enfasis mine) to imply that there are some rules to building "successfull" situations. I couldn't help but notice that there's a few recurring patterns in the situations we've been describing in the various seminars and discussions over the last couple years. These are deeply character-centric, with a strong focus on interpersonal relationships (working, sentimental, religious etc) expecially between player characters and npcs. There's also a strong focus on location and the cultural/sociopolitical/religious situation there.

The temptation to say that real play (contrasted to what is described in the 6th video as un-play) hinges on a similar set of factors is strong. I've seen it, and played it. It can be completely character-agnostic (at least at an immediate, ready-set-go level) with characters dropped in a situation that is ripe and ready to create this type of humane interactions and conflicts – who/what people loves, what they believe in, what they struggle with. Equally tempting would be to invoke genre – "drama" being an easy word to look for, "slice of life" a slightly more audacious one. I'm particularly focused on the GM as player on this, his preparation, his instrumentation.

It's people living (doesn't matter if just now or for an extended period of time) in a place with other people. You can't know what will happen. You will have to play to find out the interactions.

So naturally I wonder about other type of situations, particularly goal-oriented ones as they're those that should have all the "Danger: purple boxes ahead" warnings.

I'm fully persuaded that that type of premise is playable; I'm also well aware that through mistakes made trying to make that type of premise work a whole lot of irredimable but widespread practices were born.

So given that we have a working theory and grammar for this subject, and also an analysis of traps and how not-to, I'd like to discuss situations in detail, perhaps per-game, trying to find out if there's good practices for some specific, genre-related ones (from the dungeon crawling scenario to the spy story and whatnot).

I still have a good gob of

I still have a good gob of ideas-to-mention left in me, because the Backdrop circle of my black circles diagram is not involved in the Whimsical Ways example. I'll prepare a whole new series about some other game experience for that topic.

Your question about preparation and content is pretty dense. I can break it into several things at least for myself.

First, my distinction between un-play and real play doesn't appear, to me, to be a matter of what specific fictional content and preparation is involved. I think an extremely straightforward problem-and-action kind of adventure is perfectly viable for black-arrows-all-the-way, for example, even one in which relationships, cultural views and nuances, and character development are barely present. The temptation that you mention may be strong but I do not think it is true.

The critical features of preparation – meaning, of playable situation in the broadest possible sense – are:

The desire for "solidity" of any kind is understandable, as you need it in some things for any of the above to be the case. I am also presupposing an actual system to use, in which concepts of constraint and Bounce are operating.

Second, we should think about situation preparation for initial play vs. for later, continued play, especially when the intervals are session-based for a continuous fiction and the largest-scale situations may be fairly stated to end and new ones to begin. This is what you mentioned above, and I put you off for a while, because I think quite a bit of work still needs to be done here about entirely within-scene resolutions, effects, and responses. But for present purposes it's very plausible to say that these later situations necessarily require (or can make use of) a different bank of material and sometimes whole instruments than the first one did. I don't see this as a difficult or controversial issue.

Third, and integral to the design assignment that even now is irritating several luckless patrons, the processes of preparation, especially initial preparation, are in no way representative, in creative terms. I mean here that attention to such things as "Attributes range from 2 to 20, my guy has Strength 15, so he is quite strong," are phrased and conceived … well, not deceptively necessarily, but certainly incompletely. It may even wise to phrase them this way, who knows, but the procedural facts say otherwise. The procedural facts concern whether that number, 15, does anything in terms of authorities, constraint, IIEE, and whether the procedures include agency and bounce.

Given a "yes" to that quetion, then consider which such things are established during preparation, whether quantified as in the Strength example or not, whether big-category or tiny-detail, whether vague or precise … and how they are established, and in what order, and as assigned to whom. This exact profile of content and preparatory procedure tells us, or more than tells us, creates the potential initial situations – not because we represented (named, numbered, listed) an inventory of imagined "reality," but because we now understand what is not known and, to some extent, what sorts of things can be changed.

I expect more to come and I

I expect more to come and I didn't mean to jump the gun. It's just that these thoughts come to me rather organically and breaking them down is both useful and challenging for me. I'm looking back at several situations of recent play trying to focus on the black arrows moving into the scene, and there's constantly this big yellow neon arrow moving to the situation to distract me.

Yes, I guess my reflections were quite murky but I would say the point is pretty much that this can work for anything; I'm just observing that most of the content we created (as a community, I'm looking at the collective of AP posts) on this topic is fairly focused on a style or genre (not as in "fantasy" or "sci-fi" but what I described, lacking a better word, as "interpersonal drama") and I'm trying to see if I can apply all this to a mystery or goal-focused scenario. I suspect techniques and instrumentation would probably need to be different. There's a few recent posts about crawls that seem to do just that (even if Burning Wheel is frequently brought up and to me BW seem to be an example of an extremely character-centric fantasy game).

So what I was saying isn't "You've left out something" but rather "I'd like to talk more about those cases, eventually".

This is extremely useful, thanks.

I'm very interested in reading up whatever you can point me at about each point, or discussing it when you have the time.

I agree completely.

I think I understand what you're saying here, but the implications are instantly branching into a confusing amount of questions. For example when you mentioned "and how they are established, and in what order, and as assigned to whom", the train of thoughts following that led me to consider the risks of crystallizing the process of preparation (I'm creating locations and npcs but I'm mentally filling a form – I need a scenario for a showdown, I need a boss this strong for the character level, I need a character that holds information but can resist that character's Charm roll).

I think I need to kill the noise and reflect on it some more.

Regarding the profile of

Regarding the profile of starting information,

I certainly hope so. In the first design class I teach, which is the prerequisite for any of the others, working through comparisons for exactly this content is the first homework assignment. Your response is what I hope for most, with follow-ups that dissect the questions and find some answers, especially across different people in one another's view.