These would be Doyle (Fused Teacher/Gunkata, “disgraceful street poet”), Leonie (Focused Wardancer, “lithe lioness”), and Hans Horthy (Focused Cavalry, “getaway driver”), as I, Helma, and Hampus played them in Panic at the Dojo. Milo introduced us to the game and tried his hand at GMing for the first time.

It’s a super fighty battle-map game, full of movement and attack options, fun especially in light of playing Melee and Wizard a lot (see Laser focus); every imaginable trope is at hand for whatever dramedy you want; and if you’re interested in math talk, I see a certain affinity with the board-and-tiles game Azul.

… but hold on. Play is certainly all about battling adversity, but it is not at all competitive as purpose. I can’t point to some remarkable present-or-absent feature to prove this to you; it just “is.” Maybe if I say there are no scoring metrics, and significantly, nothing you can turn into a scoring metric, which is actually a pretty high design bar to achieve. There are textual indicators if you want, but in my case, I blew past them at first. Blink and you’ll miss the soft rules for the interstitial play between fights, which seem like nothing when you read them, but become the core.

Non-trivial point: there is nothing you really learn from reading a game text, or rather, only from reading it. In this one, you see all the pages of archetypes and styles, plus the fusing and wild versions of archetypes and the multitude of options within each style … with everything obviously tactically balanced among every imaginable digital option for fighty-fight combos. You got your control, your buff, your debuff, your armor-up, your reverser, your blaster, et cetera, et cetera.

Also, the basic actions sheet:

The reader’s conclusion is obvious: why bother going to the effort of role-playing any of this when you can get it all, and animated by pros to boot, in a thing you can buy and play, with your own damn reflexes, for what it is?

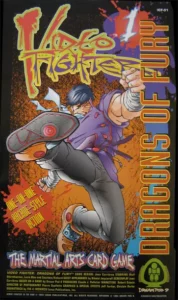

That was and still is exactly my response to Dream Pod 9’s Video Fighter: Dragons of Fury, in 1994, especially after playing it: you simulate the thing with these cards for no imaginable reason, because you can just as freaking well do that thing. The simulation itself doesn’t provide or inspire or even allow for any expression beyond saying “ooh, these designers were so clever, it’s just like a video fight game!”

You might get the same impression here, at first. Take a look at Leonie’s sheet.

- At the start of her turn, Helma gets two Speed Tokens

- If she chooses the Flash Dance stance (each character has three stances, built by the player), then she rolls 1d10, 1d8, and 1d6

- She may have an Inspiration Token from my character, Doyle, which she can spend to roll and add 1d8.

- She may now increase one of the results by 4 or all of them by 1.

- Each die gets used for a move of some kind, whether from the general sheet or the green entries inside the stance (Deadly Dance, Try and Keep Up). Its effectiveness is a function of the value showing on the die, or, in this case, as modified.

- In this stance, she gets more Speed Tokens by throwing foes around.

- Tactics are everything: this stance has no defenses, so use all that teleport + ordinary movement to get in, deliver damage and move foes around, and get out, especially to cover. [note the differences from the other stances, which are similar in general but not identical; note also that she may have Iron Tokens given to her by Hans, Hampus’ character]

And all that is true: you need to fight hard … but note again, characters don’t die, even being defeated in the moment during a given fight means you still play via inspiring your allies … and even losing the whole fight is, basically, “knocked down, come back soon” as far as characters are concerned.

In retrospect, I’m not surprised that Hampus led the way for us, because – I am guessing, so maybe – the fact that Hans got stomped in the first fight led him to consider what these fights were for Hans, i.e., why to be in them. Yes, “we won” that fight, in group terms, but why should he be involved? From that point, Hampus played his answer to that question and swept me up in it first, then Helma.

More than almost any game I’ve encountered, “playing your sheet” is quite fun but almost instantly insufficient, and expanding to playing who your sheet is about is easily accessible. Doing the latter is, however, still elective and won’t happen unless you do it. Specifically, if you play the characters, genuinely like their “way to be,” come to care about their opinions of one another, and understand their purposes without forcing anything, then you can make those purposes your own.

Also, our experience included the principle to play past the point when you’re pretty sure about a game. “Pretty sure” isn’t good enough, because it only means you’re getting a handle on the fighting options. It took one more session for Helma to go from lukewarm and barely tolerant – even after being “last one standing” and winning the first fight – to becoming a savagely enthusiastic and heroic participant.

What fights are about! is all. Because how we get into them and how they turn out potentially becomes plot of interest and consequence, about something besides our characters’ health and our players’ tactical egos. And glory be, it turns out that reading the rules means something after all. When you stop hyperventilating about apps and options, you’ll see the authors say this very thing, at every point when it’s called for, as the motive for play and its only purpose.

I spend a lot of time forgiving role-playing texts. I think in this case I’d ask the authors to forgive me, for not seeing how on-the-ball and inspiring their text is until after a couple of sessions of play.