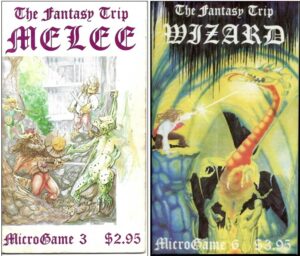

I have always found it fun and useful to have The Fantasy Trip: Melee open on the table with its sister game Wizard nearby. Lately, I’ve done so at several public events, including Spelens Hus, a mall games demonstration, and the city library, as well as a couple of fill-in play sessions when the whole group couldn’t get together. It’s an attractive draw, easy to jump into, and its value for current role-players is revelatory.

I have a long history with these games, or rather modules, discussed throughout many texts and online pieces, and I make sure to maintain play-contact with them and try to raise awareness about them, if that’s the right phrase. Melee is one of my opening exercises in the Action in Your Action course, in which it’s juxtaposed with Tunnels & Trolls 5th edition and RuneQuest “2” – once you’ve done this, only then may one compare the contemporary variants of D&D (1974, 1975 Eldritch Wizardry, 1977 Holmes, 1980 Moldvay), and understand the remarkable differences represented by Traveller and V&V. Speaking directly rather than comparatively, these two little pamphlets are the unambiguous progenitors for combat in Champions, GURPS, and all versions of D&D from 2000 forward.

Very briefly, it’s the first system which genuinely shrinks classic wargaming action-ordering to the individual’s character level.

- The full sequence applies to every round, including initiative.

- Initiative for sides is a flat d6/d6 comparison, and the winner says which side does the next thing first.

- This thing is to state a chosen option for every character on your side and carry out each one’s movement components including facing at its end; then the other side does the same. No actions are completed for anyone.

- The options are very specific regarding how many hexes one may or may not move and what sort of dice and modifiers will apply; they range across full defensive moves, specific tactics in face-to-face or missile combat, charging to attack, and longer movement. It’s all done on hexes with strict facing, and each character has their own movement allowance based on armor.

- Finally all the actions are completed in order of individual Dexterity, irrespective of which side you’re on.

To summarize and to compare with the version of AD&D I’m playing now, this is sides-oriented initiative constantly zoomed in to segment level, abandoning the one-minute unit. It is not, however, fully one by one shooter’s eye view action, as sides-based initiative is shrunk down to the segment scale. This is a serious variable, especially since often one does well to force the other side to choose options and move first, and that’s up to you when you win the roll.

Throughout all these events, the experiences with Melee were familiar to me. Since the builds are an exactly even trade-off among Strength, Dexterity weapon types, and armor type, at first, it’s very exciting in terms of elegance and logic … then it makes for rather boring play in a one-on-one fight because, unless someone makes a big mistake, it’s straightforwardly about who rolls better. Everyone playing spotted this fast and also correctly predicted that it’s more fun with multiple characters, so the decision-making is not merely a simple dichotomy between optimal vs. dumb.

Wizard adds a lot of sophistication, including significant incomplete information per side and fast-burning resources. It doesn’t work well at beginning point totals, as you burn out too fast, but at the 36-40 point total range, it’s very sweet.

For example, using 36-point wizards, Filip’s character summoned two bears, sacrificing huge amounts of Strength, then faked protective spells; and Theo’s character summoned an illusory gargoyle to delay the bears, then went invisible to stalk Filip’s character with missile spells. It was a nail-biter for guesses, rolls, and resources.

Don’t mistake this for an idealistic apex. The system does not solve or do everything, nor are its claims to special realism worth discussing. I can nitpick it into little pieces better than anyone, not only the order/action content I’m talking about here, but also the point-build structure, the probabilities, and aspects of long-term play. The point is what it teaches you if you’re paying atttention.

Perfect parity and strategic consequence is exciting at first, but it’s not enough, as play is merely a race between optima, and the race is merely a dice-off. The search for “balance” as the key to functional play is doomed and foolish.

Whereas situational contingencies and motivational differences are necessary and sufficient, such that the combat procedures are good or bad by definition insofar as they are affected by those things in any way. In this, the brief color text in both booklets is the saving grace, and it’s no surprise that anyone reading them and playing a little remembers Flavius vs. Wulf and Yzor vs. Krait for life.

It’s also why mixing warriors and wizards in some complicated monster or weird NPCs fight is Immediately irresistible … but not because it’s more tactically complex, which is merely playing longer, but because play as such would be addressing other things which the fights resolve, more contingency based on momentary outcomes, and the emotions the combatants have about that.

- If you’re interested, the course Numeracy breaks this down using the interesting, non-equilibrial part of game theory + set theory, which is rarely taught and generally invisible to popular culture.

- The course Action in Your Action addresses the bigger picture of defeat rather than death, in addition to the IIEE topics.

In such a situational context, and only from within it, the variables are so distinct, so clear, that one may properly ask “How does system operate as a component of a more general state called play?” and arrive at a real answer. These original booklets allow dialogue about it which is neither circular nor repeatedly diverted.

It’s why there is no contradiction between playing the most sound strategy as you can manage and playing your character doing what they want – it’s not a negative compromise or trade-off. It’s also why a quick “run through a combat to test the system” is a broken concept.

One response to “Laser focus”

Melee and Wizard are tactical skirmish wargames.

Like all such, they gain extra meaning in the context of a campaign. Defeat and success have consequences, and tactical situations vary beyond the range of arena duels.

An odd thing, though, is that there is a degree of separation between “campaign” and “tactical” levels of play. It’s possible to use any old system at either of these levels, or vary them over time, as long as their interaction is coherent.

For an example, Dave Arneson used various tactical systems in his Blackmoor campaign. While he used Chainmail for some purposes at some times, he also used variants of the Strategos Kriegsspiel (favoured by his group for a range of purposes). Meanwhile, his campaign systems were steadily evolving, with things being tried, abandoned, replaced or adapted on a regular basis.

Having name dropped Arneson, it is redundant to point out that wargames campaigns and RPGs share a common border.

Melee and Wizard are ideal examples for studying this border, and generally examining RPGs with as few cultural assumptions as possible. So hooray for Melee and Wizard!