This is a joint post for the fourth and upcoming fifth sessions of both Väsen and Godsend Agenda. The first is being played very much rules-as-written with a published scenario, and the second is very much the GM’s personal version of the game, somewhat different from Jerry’s (the author; the game is in development). The posts regarding previous sessions are, respectively, Skräck i gamla Sverige and When the going gets weird.

I’m putting them together in this post because the games-as-played in this case share a considerable, perhaps total baseline for what is role-playing, which I think we can address on its own terms – what is the value, how is it done, what does one do, what is different from other things. It’s also been a little eerie for me because the games have been played on consecutive days, with entirely different people aside from me, and each session has been almost exactly the same between the two games, for multiple components and events.

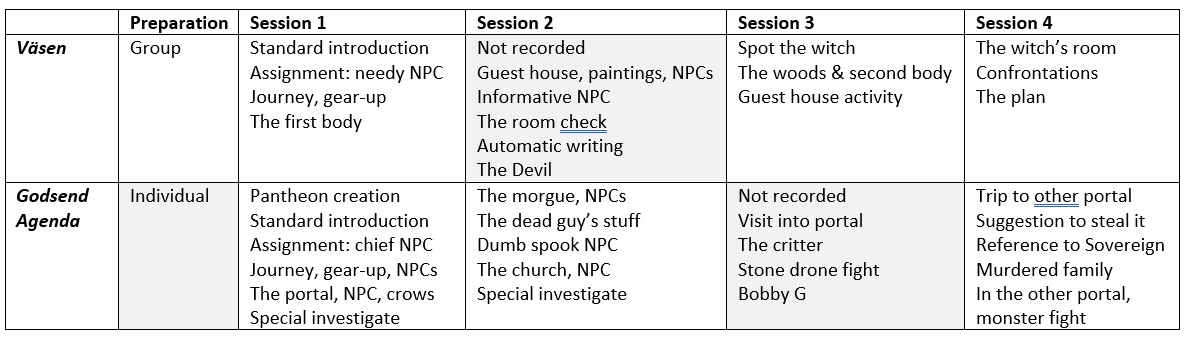

The recordings unfortunately ran into a screw-up (still not sure why the settings reverted to default on me), so one session is missing from each sequence. I’ve included a summary for the missing sessions but am very annoyed because that means both the second and the third sessions are lacking their direct evidence of being mirrors, one in each direction. Here, I’ll summarize (gray shading = no recording):

Issue #1 concerns what resolutions do, and even whether they do things at all. The most negative version is described in my Part 6 for Situation: case study, and in an effort to look at it more positively, I’d like to consider exactly how the “black arrows” and “green arrows” interact in each of these games.

Issue #2 is probably more accessible: the straight-up contradiction between “the players play their characters” and “the GM guides the story,” what I dubbed The Impossible Thing Before Breakfast some years ago. Each of these games – in Väsen, absolutely as written; in Godsend Agenda, meaning this particular application – features both of these:

- Very distinctive character creation, loaded with personal backstory, conflicting motivations, relationships, and potential for non-cooperative actions in any “team” sense.

- A specific and dangerous mystery, a complex historical origin for it, a variety of actors with their own agendas, a series of discovered clues and violent events, and a linchpin moment moving into a confrontation; as played events, all guided or maneuvered into by the GM and resulting in specific/known things.

Although the cognitive effort, even gymnastics, of “making it all fit” as an ongoing task can be considered a challenge, I think it’s insoluble as stated. Ultimately, one of these happens:

- Diminishing what the characters may actually do (as statements and resolutions; as actual effect on events) or even removing it, so that the characters do what’s needed to follow what’s planned, regardless of what the players say or do

- Constant re-casting and re-tooling and re-planning, per session and even per scene, of what must be retconned or invented to keep the plot in place; the plot is re-Legoed as needed so that whatever they do turns out to follow it

… which amount to the same thing. Here I’d prefer not merely to dismiss it but to acknowledge that person who is GMing, for this sort of play, is under extraordinary pressure. They are expected, not least by themselves, to conceive, present, and perform “the story” which makes everyone else feel good about participating in it and which also makes everyone happy as a story, as such. The perfect analogy is the chef: it is their responsibility to make it good, and yet they are subject to everyone else’s ungovernable needs and desires. Furthermore, the players have no responsibility even for their own tastes – if they don’t like it, then the GM did it wrong, and that’s that, or at least, that’s how this person is expected to feel.

I admit up-front that this is definitely not my preferred way to play, and to some extent sits outside of my framework of what play even is, but I can also say that it’s a viable topic here, to be treated courteously regarding the two games’ organizers – and given my position about it, if I’m saying we take it on its own terms, then you can do the same.

* The second picture in the lead image is from our very own Ola!

Direct link to session 4 for Väsen inside its playlist

Direct link to session 3 summary with session 4 following for Godsend Agenda, inside its playlist

11 responses to “Neck and neck”

The Tragedy of the Impossible Thing

I certainly know the pressure you're describing on the GM when running this kind of scenario. What's probably most frustrating is that it's easily resolvable in either direction. I don't mind and even enjoy running this style scenario when they are well-constructed (and a lof of them are not). The better ones don't have forced outcomes that are somehow supposed to magically happen with the PC's actually present. When done well, the result is a kind of navigated puzzle built up from challenging encounters linked together by information.

But the key to making that work really well is that you absolutely must not do this:

Even back when I was running Chill scenarios in pre-Forge days I was always a bit baffled how the various personal issues of the characters were suppsed to "fit" with the information driven scenario. The simplest solution is to accept that they don't.* It's far better to think of "the group" as a swiss army knife with multiple personality disorder. Different personalities "emerge" to handle different problems along the path in whatever colorful way makes them happy.

The fact that "mystery"/"monster hunting" games after game continue to build this contradiction into themselves is utterly confusing to me. I think it's out of some misguided notion of Drama. That somehow the PCs are supposed to have tension between each other. That there should be performative but non-distruptive tensiosn and conflicts between the PCs because that's ROLE-playing!

The real tragedy is that I think Vaesen in particular is ripe for resolving in the OTHER direction. The premise of "the industrial world is disrupting the old folk world" is just too good to abandon to a clue-chain hunt the wumpus scenario. I agree with the sentiment expessed over on the Patreon that the game deserves better situation prep and execution procedures that would allow the players to really truly grapple with the conflict at the core of the setting.

If I ever run Vaesen I'm pretty comitted to trying to do just that.

*A notable exception might be Graham Walmsley's Trail of Cthulhu and Cthulhu Dark scenarios which feature pre-gen characters whose personal issues are intimately tied with the dynamics of the scenario which are themselves written in a slightly "looser" manner that others of their kind. I litterally refer to them as a "magic tick" because they somehow pull off The Impossible Thing Before Breakfast in the same way a magician does the impossible thing of levitating. They rely on some serious psychological slight of hand I have yet to figure out despite having actually played them multiple times.

I completely, complete agree

I completely, completely agree with you regarding the potential power of playing Väsen "black arrow"-wise, to borrow my casual terminology from the recent presentations. All the other players have independently raised the same topic, having felt the barrier or disconnect between [who the characters are + the historical issues + the mythology] and the purported value of playing through the "purple arrow" adventure, which I maintain cannot even be called play.

Considering our fifth and final session (now being edited), I have found that the game's single really good rule is the critical injury mechanic. Played into this and through it, everything else changes, especially the relevance of the Conditions' rules, which are otherwise trivial. I know that if I were to repurpose the game as you're describing and as at least one player is informally writing right now, I'd consider critical injury to be the linchpin of the system, and that everything else is played in the context of its potential and its likely presence.

However … bluntly, I have been repairing published games in play in exactly this way for, let's see, forty years, almost continuously. I'm a bit worn out with it, especially butting up against the social resistance and doubling-down on "purple arrow" control … and the willful blindness to it. To cut a little close to the bone, for purpose of a relevant example, I'm especially tired of Burning Wheel, whose texts write checks that its ass does not cash. The game does not play anything but prepared skits unless someone like you fixes it.

Let's stop claiming games are fine or good because we bust our humps so hard to play a good version at the table. They need no favors; their authors and publishers gain far more hobby cred and financial gain through publishing this broken mess (and it's always been the same one, for forty-plus years) than you or I will ever see, and that's all they care about anyway. Let's look instead at the processes and contexts we have created in play, in doing so, and call those the good systems, unto themselves.

Structure vs Play

This is a really big topic for me, expecially when you allow it to branch into its ascending and descending relationships with genres and "types" of games.

I'm tempted to say that there's a relationship of inversed proportionality between how much input players have in creating the situation (vs GM prep) and how authorities are distributed in scene play.

I'll try to explain: the more a situation is character-centric, as in it's about these specific characters from the get-go, and keeps caring about their direction and wants and needs as it evolves, meaning that the situation changes and scenes are resolved when the characters do and decide to move on, the more "play" can handle a strong reliance on GM authority for everything else. This is how I feel a lot of the interesting heartbreakers that were played/discussed in the last couple years of Adept Play managed to function despite having GM-facing rules that invited the same type of behaviour described here: GM-prep and character creation gel really well into producing a starting situation that (with some care) will rely on everyone at the table playing (for real) to function.

If however we look at what I've been referring to as "goal-oriented" play (even if it's a terrible definition and should probably revolve around something mentioning pre-play or preparation) then I feel there's a significant external element to consider. Let's consider such games as The Hour Between Dog and Wolf, or even Cold Soldier (or My Life with Master), and on the apparent opposite side of the spectrum something like Torchbearer or AD&D – any game where either by rules prevision or because of ritualized playing habits there's one or more element that is external to both GM-prep and character creation/growth, and probably predates both.

A murder happened and finding the culprit or escaping capture will be a significant goal of play.

We will delve into dungeons and recover as much loot as we can.

One or more characters will confront their master or nemesis and we'll see what happens.

We will reach Lidinsfarne and burn the witch or let her go.

We have been paid to hunt the werewolf.

This element, this "goal" that is explicit before play (I'm ignoring for a second the potential for it being abandoned in play, ie "we came to hunt the werewolf but now we want to kill the duke instead") alters the way all prep and all the situations of play will come to be, in my opinion. And (going back to my original point), its "presence" requires that the rules of the game, the way authorities are distributed account for it, because it's going to eat into some of the agency of all the people at the table.

I think this goes past agendas or playing on purpose – simply agreeing that we're all fine with this premise and this is what we want to play won't remove the need for the game to provide the means to play successfully with these goals in place.

I think this issue is displayed across several, very different games. From being the core issue of failed play in the AD&D2/"paladins and pricesses" playstyle (where the goal is set by the DM, agreed upon by players and then asymetrically handled by the DM through the entire life of play) to a lot of modern storygame design (where the strenght of the premise/goal is so suffocating and so strongly enforced through play mechanics – to avoid the risk that play can fail by not meeting the goal itself) where the entire experience is performance.

I think this is valuable mind

I think this is valuable mind-work but, due to some persistent assumptions, still kind of a mess. Let me see if I can break out the separate things to consider.

Here’s what I’m seeing: #3 is overwhelming you, based on past experience, and I think you’re blaming it for something it doesn’t deserve.

Let’s consider one little part first: situation as such, as a played thing. Consider any concept for player-characters that a game may require or offer as a list, as they are very common. These requirements are themselves situational, because they are in it and part of the definition of “situation” as a played phenomenon. Therefore “you must play a trollbabe” is conceptually the same design feature as “you are minions of a terrible master” – it’s fixed content, again, in order to play at all, no matter who makes up the details or who has the primary authority over it during play.

I think you’re assigning some baleful influence for non-specific requirements, as you write here:

Clearly, I agree with your observation. However, I suggest that any distribution of authorities, so long as it’s consistent with and mutually reinforces other rules in play, has exactly the same property. What’s striking you – I think – is demolishing the myth that “a strong GM,” e.g., backstory authority + substantial situational authority means decreased player agency. This is indeed the historical case, but that case is not actually a property of play but the result of bad design, specifically for outcome authority, and a broken/shitty hobby context which instills loyalty to the subculture, and its commerce, over assessing design, or, bluntly, over even enjoying play.

I suggest instead that a game which does in fact include content which must be accepted and embraced in order to play at all … is not a big deal in principle. As with everything else, its local application for a given game matters very greatly. But it doesn’t necessarily or generally mean anything regarding the other variables.

(continued in next comment)

This element, this “goal”

I think you are wrong, about any such thing interfering with agency. Maybe we should review that concept. It is not “freedom.” It is not “make up what you want.” It is not “do whatever you want next.” It is not “power” in terms of defining or stating something that is, or something that happens. All of those things are broken design for the various authorities, and they have broken many of us as people, ruining our enjoyment and our hope that any such enjoyment is possible. I need you to get out of that, which fortunately is almost accomplished; play has done the real work, but now it’s about thought.

So, what is agency? It is the observable effect that who you are, as a person, matters as an effect upon the events of play. That’s why “you get to narrate!!” is not enough. The bigger issue is when you say something, within the constraints of what is possible to say, subject to what has been bounced … when what you have said, and its effects, are constraints upon subsequent play. If someone else playing that very same character in that very same moment could have and might well have said something entirely different.

Contrary to all the rhetoric, it is most apparent at the points when you have the least situational options and the most instrumental constraints on your outcome authority, i.e., super not-free in mechanics terms. Examples are available upon request, but I suggest considering anything from your own play experience first.

You are right that there is an issue to consider, for what you’re describing in this paragraph. However, it has nothing to do with the fixed/embraced concept of play content being present or absent. It has instead to do with the expectation that any character played by any player must perform and respond precisely as pre-conceived, as far as any activity which constrains and affects later play is concerned.

In everything you’re mentioning here, there is no agency at all: all “role-playing” is pro forma, because it really doesn’t affect outcomes at all. It consists of the single and assigned thing to do for you, on your turn: blither something colorful and irrelevant, roll for observation, for investigation, roll to attack, spend points of various sorts. You can throw in accents and hats and quips too. The next person to speak, however, whether the same every time or distributed widely, doesn’t have to listen to you or care, as there is no constraint or conseqence of interest.

Regarding authorities, this is about separating situation’s fixed content from outcome which utilizes hard constraints. It’s particularly relevant for My Life with Master, for those who are confused about why the Master is guaranteed to die, and why strategizing toward the final epilogues never seems to work. The game’s solidly-central, non-negotiable situational content does not permit either pre-determination or opportunistic control about how the things that matter turn out, nor does it distract with a false boss-fight resolution.

The presence or absence of

I think this warrants a few clarifications, expecially considering that the observation you made is on point about the crux of my mental contortions.

First, I think I've framed my argument too much toward the idea of this being a problem while, in fact, I don't disagree at all with the idea that all of these things are perfectly functional and don't come in the way of play or agency.

Secondly, considering that all of what we're describing is perfectly functional, I would consider that for the sake of this discussions things as "you need to play a Trollbabe" or "we're playing Undiscovered using only these races" or similar situation-based requirement are one thing, and not difficult at all. I'm focusing on elements of the situation that strongly imply some pivotal event that is supposed to take place or at least be confronted (avoided, thwarted, refused) some way in future play. I've called this "goal" even if it's probably a terrible term as it implies that the timing and placement of this event is central and climatic, while I would say it isn't.

Examples of games with this element of situation would be the already cited The Mountain Witch, exploration-based D&D ("we're going to the dungeon/we need to kill the dragon"), a large part of investigative fiction (I'd say Call of Cthulhu and I do so knowing that a large part of its applications are not-play of the highest magnitude) and others already cited. Perhaps paradoxically, I would say TMW applies more than My Life With Master, because while in TMW facing the witch in a climatic showdown isn't necessarily happening (or at least not for every player), the presence of this looming event informs play on a deeper level than the certainity that the master dies in MLWM honestly, I can't remember a single instance of play with that game where the knowledge that the master was 100% going to die influenced us as, like you say, the game is incredibly rooted in its situations and never lets you build expectations or anticipate events.

I think it's highly possible that these two games are precisely what I should look at, because while there's no expectaction for the players to accellerate or force these events, the mechanics of play do take care of making sure that consequences build from scene to scene and lead to players creating and facing outcomes.

Maybe this is a focal point: if the situation introduces or implies some sort of climatic or goal-oriented event, it can become problematic when its introduction and resolution is left at the discretion of a single player with little to no bounce from the others or the system.

No disagreement of any kind here. I'm sorry I framed my post so poorly – I would go as far as saying that instead of being problematic, the latter part of the statement may be a requirement for play. "Let's run Forgotten Realms" is, in itself, an unplayable premise.

As for the former statement, I think it adds to this:

I think you would find some strong resistance on both statements across different roleplaying subcultures. Not from me, but saying "a strong GM isn't necessarily problematic" or "agency doesn't equal to being able to say things with no resistance or restraint" will send a lot of people I know spiraling.

I like the way you described agency; for both this and the statement above, I feel outcome is a crucial topic and I'd like to discuss it more. It feels like many of the things we've discussed here or recently – the potential for a strong DM to be not problematic, the importance of situations, outcomes and consequences, the importance of restraint and bounce – emerge once again as central to this topic too. The more I think and discuss about it, for example, the more I think preparation is crucial for this type of play, on all sides of the table.

And going back to the above mentioned resistance, I think adding up those elements could be considered downright heretical in some circles. Not an issue for me, but it's what I would expect.

Agreed, and I feel very similarly towards TMW. This is a place where I feel design is crucial and I hold both games in very high regard in this light – because they do "the thing" I've been wondering about extremely well.

I have my own selfish reasons for exploring this subject but I think it can be extremely relevant for many people playing many different games. I also have a strong bias toward those pesky "boss fights" but I understand that the way they're used as climatic, inevitable moments is absolutely problematic because having a necessary landing point not only kills all the game's momentum (and here is irrelevant if you can later avoid the fight/climax, if all that means is resetting things with a new boss fight in tow), but makes whatever happens sooner irrelevant.

It's about designing games in a way that you can tell people "this is a game about killing dragons" and in practical terms not making it about the act of killing dragons, but about people who are tasked of killing dragons. If that makes any sense – a bit as if I was saying that TMW is a game about the characters' dark secrets, with a witch-antagonist acting as a catalist for the story. At least this is where my mind is at the moment.

I think you would find some

I bathe in their outrage and spit in it when I'm done.

Finishing both games

We played our final sessions: Väsen session 5 and Godsend Agenda session 5, both linked into their respective playlists. They were similar, much as the initial sessions were: in this case, a final-fight + insight-twist, strongly focused on providing a "now it all makes sense" moment as well as identifying/providing a specific task or action which solved the immediate problem.

I give Peter a lot of credit for reflecting about the game, especially his own sense of being trapped in the procedures and content of the scenario. He shared the text with the rest of us so we could all process what kind of instructions he was working with. If you're not familiar with Väsen, you will probably not believe the extent to which the core rules and the published scenario template script out play. It takes the 1990s Shadowrun/Vampire model into new territory of pure, guaranteed, beat-per-time-unit delivery.

A single glance at my diagrams from the Situation: primal and primary post was sufficient: Peter pointed "here, here, and here" on them to exactly what he'd felt compelled to do, and – again to his credit in saying this – had been encouraged to do, and found hard to break even when he wanted to. I sketched this as we talked:

The idea here is that the game provides fantastic backdrop and character creation consistent with it. You get excellent late 19th-century Scandinavian characters, very much of their culture and its contemporary issues. They very likely represent a range of social classes and outlooks, a range of genders and orientations, a range of ages, and significantly, personal histories of occult experiences and PTSD. They even include baseline opinions and emotions directed at each of the other characters. They are bursting with play-potential for idiosyncratic and personal activity during play, and furthermore, with potential for changes and growth that can only be produced by the events of play.

Certain aspects of the system are well-suited to such play. Characters gain Conditions all the time, in various states of mental and physical distress. The penalties applied due to Conditions make critical injuries more likely, both mental and physical, if the characters face dire straits enough. And critical injuries, far from being disastrous (well, to the characters they are!), unlock awesome, awesome things – at the least, disabilities or effects which serve as dramatic consequences and springboards; but also, occult and metaphysical abilities, opening play into new realms of interacting with the väsener. Anyone with any desire to play an RPG will slaver at this chance.

Then you put these very characters into a situation not of their making or volition, you trap them effectively in a dinner theater LARP, and you take them through the scripted beats of what they see, learn, know, and even do. Conditions clear as fast as they're gained. Player-determined activities which grant rolls are and aren't effective as dictated by the state of the scenario. The necessary "so that's what is happening" and the mcguffin to solve/stop the problem are provided at the designated 4/5 mark. None of what I just described happens.

There is more to say about the content of this scenario which I'll leave for further discussion. I'm talking here about the general nature of these publications. It's not a "style." It's not a way to play. It is a full betrayal of the activity and anyone who tries to do it, and it is an outright disgrace.

Yup! I was super sad when you

Yup! I was super sad when you mentioned early on that you were playing a published adventure because… well, everything you posted. It's like two different people wrote each half of the game and then they just glued them together in the most lazy way imaginable.

I'm glad your observations line up with mine. I'm pretty confident, you can just develop/play situations differently and the rest will play fine. I remember thinking, "Why don't you just prep this like Dogs in the Vineyard or something…" Although, you mentioned that Conditions recover quickly which might be a problem on its own. I had not consideerd that.

If I do play it scrapping the adveture design assumptions, I'll post about it.

Scrubbing an enormous amount

Scrubbing an enormous amount of the text in the second half of Vasen is likely the best way to handle the situation. It seems like it takes all of its play elements from the scripts of Murder She Wrote, where no matter how the NPCs suffer or what evidence there is, JB Fletcher gonna remember that small fact and find the killer. But in this case, Vasen characters are those long suffering NPCs surrounding Jessica who are more a part of the background than the actual play.

But you should not have to pull out your red pen to this extent to play a game. I am learning, slowly, that I need to be more critical of a game that does things like this, even if I feel capable of making changes to it. I have a lot of experience running Year-0 Engine games and so I do, but that does not mean that Vasen does not have major issues. It does. I have a few ideas on how I would run it, but going to leave them for now.

Modules (Adventures) At Play

This is tricky to talk about and I think it deserves a larger discussion than we might have here. But modules are a set of weird constraints and opportunities that may have very little to actually do with the system they are designed to provide a situation for. It sounds like this "adventure" does reinforce how the game is supposed to be played, for better or worse. Ron, you got to see some of it, was there any place where the adventure mentions or encourages going off-script?

After a while, over the years

After a while, over the years, I realized that revising RPG texts' preparation and presumptions for play had become standard for me, to an absurd extent. These days I set myself a high standard: if the text seems off a little, or not quite what I'd prefer, or (as is often the case) struggling a bit with itself over things I find high-potential, then I can do it. There has to be something in there which really excites me about playing, i.e., not presenting, but seeing what comes of it in play. Some games like The Whispering Vault and Zero are favorites for me because the effort may be real but it's so minimal I feel like I'm clarifying rather than revising. Khaotic and Undiscovered are excellent examples of more directed revisionary or focusing effort that turned out more than well; my version of Mutant Chronicles might be another, as I presented in a Patreon video. Just "ronning" the already-present content a little for preparation and interpretation is enough. Sometimes it's more about a procedure I'd like to enjoy or some aesthetic I'd want to celebrate, e.g., Lace & Steel for both of those, for which I'm willing effectively to write my own "GM and play" section from scratch if I can find some people who are excited about those things too.

But so, so many games are below that bar to me now. I can't imagine caring enough about anything in SLA Industries to revise content, preparation, and presumptions to the necessary extent in order to play … or in Tribe 8, Feng Shui, Bureau 13, Everway, Nephilim, Conspiracy X, Earthdawn, Space: 1889, Reign, and those are just off the top of my head and don't include at least 50 small-press, generally unknown games. Väsen is tragic to me because the "A" of its A+B is so good but the "B" is so, so void that I feel justified in asking for money from the publisher if I went to the effort of making it playable rather than controllable.

Sean, the adventure we played is called "The Night Sow," one of four unconnected scenarios in the supplement A Wicked Secret. The answer to your question is a flat no. These are scripted, read-out-loud, directed episodes with multiple ways to redirect characters and punish players who stray off track or push too hard. For example, in "The Night Sow," if anyone further questions the adventure-initiating NPC Linnea after she has delivered her scripted clue (the letter from Olga) and given the players their direct instructions to go to the guest house, she is supposed to melt down and have a seizure.

… which in addition to its role in scripting the events, frankly grosses me out, assigning the role of abusers to the players and utilizing the character in a fashion I consider exploitative and dehumanizing.

Anyway, if the instructions you're seeing here seem familiar to you from Call of Cthulhu and Chill, you're right, but allow me to assure you that the degree of control of events, management of outcomes, imagery, the player-characters' perceptions and sensations, and even their very thoughts, operates at heights never achieved by those games even at their most controlled.