I’ve been avoiding writing up the AP report on the last two sessions of our Runequest: Roleplaying in Glorantha duet.

I’ve been avoiding writing up the AP report on the last two sessions of our Runequest: Roleplaying in Glorantha duet.

My buddy and I took a break from RQG to play a couple of sessions of Emet (from Doikayt: A Jewish TTRPG Anthology). With the two of us trading places and me no longer in the GM seat for RQG, I decided to avoid anything that looked like prep until we started playing in earnest. I am slavering to see what my friend dreams or nightmares up in Glorantha, and I didn’t want to step on his toes. However, if I still had the AP report to write, it meant this chapter hadn’t yet closed.

Cut to now and my buddy is GM and my brand-new shaman’s apprentice is almost ready for play (minus a few small details, like a first name). Time to bring it home.

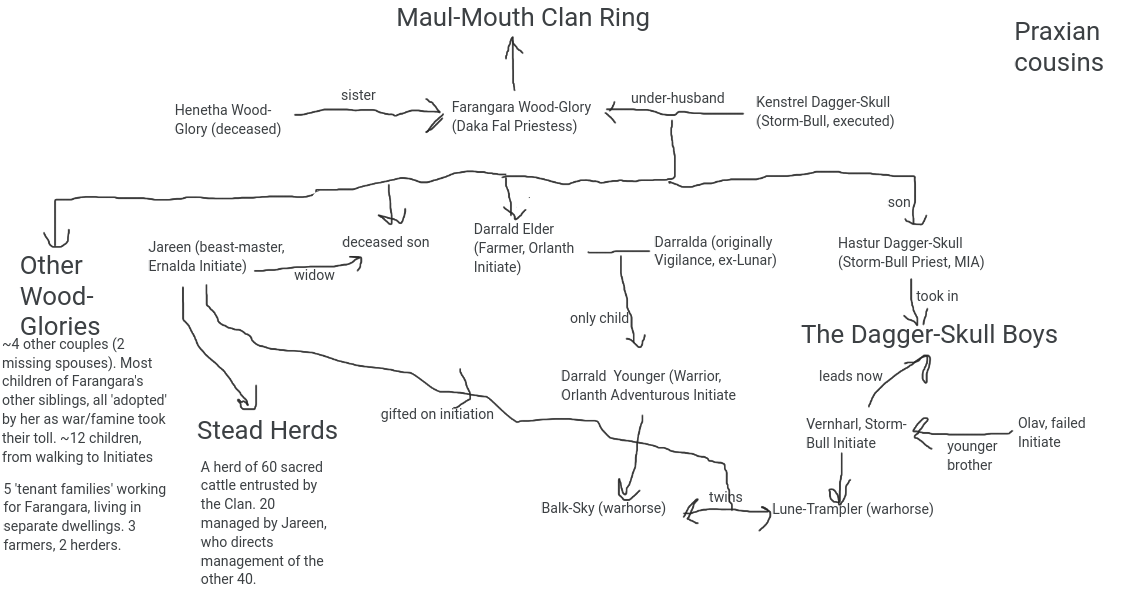

The R-Map as it appeared in session 1.

The Flight

Session 12 opened with Narmeed rejoining Marlesta’s Storm-Bulls and his companions after the miniature apocalypse at the Dragonrise. The Resistance rolls and Skill checks of last session had meant: A delay in getting on the road, meaning the band’s pursuers were closing in, the capture or possible death of Darrald, the (ever more improbable!) survival of Willandring, and the death of Soran, Vernharl’s lover from Lhankor Mhy. We the players knew of Soran’s death, but Vernharl did not.

My prep was fairly simple: determine who was on the road out of the Dragonrise, how far Lismelder’s Hammer-and-Bellows Men fled before they regrouped and returned for revenge, and who exactly (stat blocks included) would be part of that pursuit.

The reunion was rushed. This was when the full consequences of last session’s events came crashing in on us.

Narmeed and Vernharl had no way of locating Darrald. If they went westward to return to Olontongi territory by road, news of Lismelder’s death would precede them, and every Orlanthi and Lunar-hater in Sartar would descend on them. If they took the Troll-paths back to the stead (and outwitted the machinations of Pebbles and his troll-brothers), they would only delay the same outcome, while also bringing armed and vengeful Rune-Lords down on their loved ones.

With no choices left to them, Narmeed and his band turned their faces east, to Prax. Narmeed’s Storm-Bull companions quickly divided the loot. Narmeed said tearful farewells to Willandring, and Narmeed gifted her a hefty sum of Lunars and entrusted her with Farrangara’s Trollish Darkness amulet to carry back to the stead.

Vernharl asked Willandring to tell his brother Olav that he loved him, that Olav could never disappoint him, that he was sorry if he ever made him feel differently, and to give him the traditional Praxian farewell: “Tell him this is no good-bye: I will see him again next season.”

Willandring’s grief over Petrada’s death had been an invisible thread running through the last four sessions. We hadn’t seen it on-screen. I had been ‘checking in’ with Willandring between each session (thanks to Champions Now for this approach), occasionally using Passion rolls to determine her disposition. There were moments when she was close to suicide, but the knowledge that she was needed alive to purge the Chaos-curse from the stead stayed her hand.

The necessity of burying Petrada, the mad flight from the Dragonrise, this new responsibility of carrying resources back to the stead—I think duty to her kin carried Willandring through those darkest moments. I am also now realizing that Vernharl’s request must have pierced her “Where the Meanings, are –”, a chance to give Olav the farewell she would never be able to give Petrada.

The last time we saw Willandring she was a small, solitary figure on the wide King’s Road, determined at last to accept the hospitality of her kin, even if that meant having to fight them for her autonomy.

In the few hours left of daylight, Narmeed led his band along the King’s Road. They passed the white-wafting tents of the Lhankor Mhy, encamped near the eruption to better observe and record the Dragonrise. Narmeed reluctantly agreed to Vernharl’s request that he be allowed to return there in the morning and say a hasty farewell to Soran (an opposed Passion check meant Vernharl did not sneak off to the Lhankor Mhy during the night).

The band set off, away from the road, and found a hidden spot in the wilderness to wait out the dark. An opposed Survival vs. Scan (Visual) check between Narmeed and the Hammer-and-Bellows Men pursuing meant their camp was not as concealed as they believed. A Listen check resulted in Narmeed, on watch, hearing the creak of leather and the soft clank of armor in the middle of the night.

The Fight

He had just enough time to swing into the saddle and rouse his companions (I decided the Storm-Bulls leaped up and were ready to fight straight out of sleep, as this seemed entirely in line with what we knew of their lifestyle), when a line of Hammer-and-Bellows Men and a rider on a mysterious steed descended upon them. An arrow loosed by Narmeed brought the rider down, and then their enemies were upon them.

Marlesta cast Light (the horns of her Storm-Bull helmet blazing), and in the bright shock of the Spirit Magic Narmeed and Vernharl found themselves face-to-face with Hastur Dagger-Skull, a brutal, brutalized hulk of a man bearing the faded tattoos of Storm-Bull and the fresh tattoos of the Dragonrise Cult, his hands grey with forge-ash. His left ear had been torn off, and Narmeed remembered the Divination Ceremony in session 11, when Storm-Bull had told him that, if he abandoned the cult, “One-Ear will tear you like he tore Hastur.”

A bit of background: Hastur had been captured by the Lunars and imprisoned for months, his bound spirits killed, his cries to Storm-Bull unanswered. He had joined the Hammer-and-Bellows Men who rescued him out of his hatred for Lunars, and suffered Storm-Bull’s Spirit of Reprisal as a result. He’d been within shouting distance of Vernharl and Narmeed since session 11, when he’d arrived at the Dragonrise Temple as part of the escort of Lunar sacrificial victims. Multiple failed Scan (Visual) checks meant they never picked him out from the uniformed lines of Dragonrise warriors, and his ceremonial duties kept him from approaching them.

Hastur was also one of the group that captured Darrald. They’d left him prisoner at the Lhankor Mhy tent. Across this session and the last one, two Opposed Passion checks of Love (Wood-Glories) vs Hate (Lismelder’s Murderers) meant Hastur had refrained from torturing or maiming his kin. Darrald was battered and ill-treated, but Hastur surprisingly kept his sadistic inclinations in check, unable to harm this young man he’d watched grow up.

Now, he shouted his anger at Vernharl for abandoning him for Narmeed, his hatred of Narmeed for killing Lismelder and stealing his surrogate son, and launched into combat.

I’m not going to describe everything here. I handled the battle between the Storm-Bulls and the Hammer-and-Bellows Men using abstracted opposed combat checks at the end of each melee round. We focused on the area of the battle where Hastur and a companion fought Narmeed and Vernharl.

Narmeed cast Fanaticism on Vernharl, who, still stained blue by last night’s Woad, attacked Hastur mercilessly.

At my buddy’s suggestion (a pivotal, oh-shit moment), Vernharl called upon his Love (Olav) Passion to augment his combat abilities, remembering how Olav’s failed Initiation at Hastur’s hands had left him physically disabled. A successful Love (Wood-Glory) Passion roll meant Hastur could not bring himself to strike his young ex-follower. Instead, he parried Vernharl’s attacks while blasting Narmeed with Orlanth’s Lightning.

Since he didn’t have his sword drawn, Narmeed suffered a bad wound from the other Hammer-and-Bellows man and took the Lightning full-force. He dropped to the ground, temporarily out of combat, and while sword-play raged between Hastur and Vernharl, he desperately cast Healing to get back on his feet.

Vernharl wounded Hastur’s left arm, while Hastur continued to refuse to strike back. When Narmeed got back up, Hastur scripted another Lightning blast that could have taken Narmeed’s General HP to 0. Instead, in a fantastic confluence of choreography mechanics and characterization, Vernharl scored a Special Success on his attack roll and struck Hastur’s arm again, severing it one Strike Rank before the Lightning left it: Hastur’s lopped limb hit the ground, still sputtering with divine power, and Vernharl, still under the grip of Fanaticism, finished him off mercilessly.

Aftermath

The first cold light of morning found a hollowed-out Vernharl trying to process that he had killed his own mentor. Narmeed spoke to him kindly, did his best to comfort him, but a Loyalty (Hastur Dagger-Skull) v Loyalty (Narmeed Wood-Glory) meant that Narmeed’s words did not reach him. Vernharl will leave this chapter still haunted by the man who raised him, the abuser he killed.

Session 13 opened with Narmeed having to face a new problem in the mysterious rider he’d brought down during the battle. This was a Dragonewt, badly injured, who was still guarded by the dinosaur he rode.

We’d been planning on a full session. But halfway through the week we were texting and it hit us that we’d answered all the thematic questions that had driven play. This was surprising, as seemingly essential events, particularly who had been lost to the Chaos disease back on the stead, were still unresolved. And yet there it was, staring us in the face: for Narmeed’s story to continue, we would have to create his new situation. It reminded me of people talking about Kickers in Sorcerer resolving themselves almost spontaneously.

We decided to treat this session as an epilogue, wrapping up a few loose ends and considering some long-term consequences.

Narmeed used Intimidate, augmented by his Ride skill, to ride Hearse and chase off the dinosaur. Because no one in the band had Xenohealing, Marlesta had to (just barely) make a First Aid check to bring the Dragonewt back to consciousness.

This was Sarna Ya’Qal, a Dragonewt heretic who’d abandoned his people to help Lismelder Trueline delve into forbidden draconic lore. (I’d lifted his name and stat block from a Dragonewt in the Game Master’s Screen Pack). He and Narmeed spoke with great honesty, Narmeed questioning him about the mysteries of Dragonewt incarnation, Sarna Ya’Qal informing Narmeed of the ransom he could get for returning him to the Hammer-and-Bellows Men, or even his fellow Dragonewts. I very much enjoyed playing such an alien being, with an inhuman perspective on time and consequence.

Narmeed decided he could not allow Sarna to go free, lest he reveal secrets that would allow the Hammer-and-Bellows Men to continue courting Chaos. He told Sarna he would send him back into the cycle of reincarnation as painlessly as he could. Sarna’s final request was that Narmeed return his ancestral weapons to the dragonewts. He promised Narmeed they would meet again, perhaps on opposite sides of a blade.

Narmeed’s last roll was a failed Peaceful Cut. Sarna was not mercy-killed. He was murdered. This felt like an appropriate coda to our rather brutal story. Here’s hoping we get the chance to see Narmeed make something gentler of his life in the future.

We wrapped this game of RQG by establishing that the Wood-Glory stead did not have the resources to pay Lismelder’s weregild, and no warriors to protect themselves from avenging Orlanthi. They had no choice but to declare Darrald, Vernharl and Narmeed outlaw, no longer kin. It was that or annihilation.

And now I’ve passed those open situation questions—Darrald’s fate, the fate of the stead, Willandring’s journey back—into my fellow-player’s hands. “This is no good-bye. We will see you again next season.”

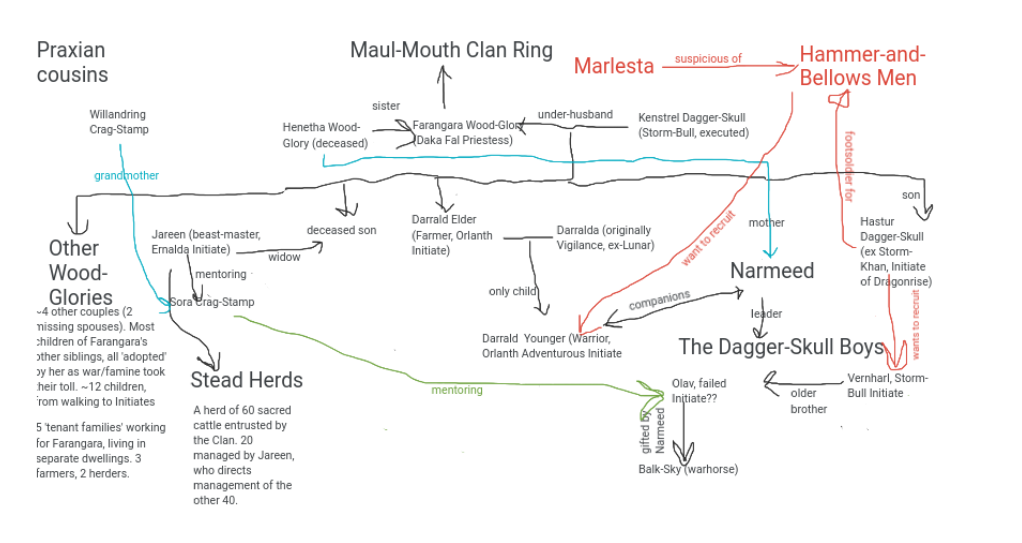

The R-map as of session 8

9 responses to “Bringing It Home: RQG Sessions 12 – 13”

A quick question first

There are lots of things to learn from regarding the game, but your first paragraph was like a distracting sign on the way to get there. Why have you been avoiding or delaying writing about it?

I suppose I could be overreacting because you meant nothing more important than, for instance, not having the time until now. But just in case some other meaning or content is involved, if so, what is it?

Thanks for pointing out the

Thanks for pointing out the murk there, Ron. Consider this the rewrite of the intro.

I've been avoiding writing this AP report for two reasons:

Morality

I really tried, but I have not succeeded in liking Narmeed. Yet that’s not a bad thing, and it leads to thinking about the distinctive features of this particular RuneQuest. In mechanics, clearly the Passions are the standout, but there’s a thematic component to that. That technique is ‘ported over directly from Pendragon, which is based on Le Morte d’Arthur, so the behavioral and plot effect is similar to the knights in that story – they have terrible impulse control, to the point of several of the protagonists being outright deranged (*cough* Lancelot). Nearly every story in that source is summarized by “How I lost my shit that day and everything went higgledy-piggledy.”

It does fit, though, because one of the big influences on the early RuneQuest was the Nordic sagas (Njal’s Saga, Egil’s Saga, et cetera), which are pretty similar: big meltdowns and violent swerves, with consequences rapidly spreading across communities and down through generations.

The difference concerns player decision-making and statement of actions. It’s pretty much night and day: in the other versions of RuneQuest, the character does and says nothing except what you say; in this one, the character’s behavior is often triggered into wild forms at the drop of a die, leaving you gasping in the wake of, e.g., a murderous attack on this guy you thought you were just talking to. Or abandoning your dearest friend. Or arresting your attack on your hated kinsman, resulting in getting fatally impaled.

Both work. Both work rather fabulously, in fact, depending on how other aspects of play get invoked and used, especially social stuff. But they aren’t the same. In earlier RuneQuest and I submit accentuated in HeroQuest, the player’s morality is expressed directly (perhaps filtered, distorted, or even subverted) via the character’s actions and their consequences. If you take it to the degree encouraged in some RuneQuest texts and made explicit in HeroQuest, you literally create new moralities and metaphysics, as far as the setting is concerned. If you don’t get that far, it’s still quite possible to cast judgments upon the NPCs and cultures you encounter and belong to; the hero, if you will, is “free to judge” and the player is sort of that hero’s Anima or whatever other non-linear relationship you’d like to propose between author and often surprising character. Intent in IIEE is all your intuition and imposition; Bounce is largely an effect of what you say they do, upon other things.

Whereas in Runequest: Playing in Glorantha, one is rather at the mercy of powerful surges of emotions and decisions, because Bounce comes in hard upon the Intent in the first place, quite often. The character presents “I do this” to the player, and therefore the morality is rather … reactive, or two-layered: doing that was entirely heartfelt, but now, having done it, was it right or not, so what do I do now? I am really interested in those next decisions during play, the ones based on reacting to what one just did, as the sphere for commentary or, especially, actions which serve as commentary.

In earlier RuneQuest and I

This is a great point Ron. I've been unraveling it to myself for a few days now, and I look forward to bringing it as a lens to the next RQG chapter. I think it’s worth emphasizing that this two-layered moral reactivity applies to all characters, PCs and GMPCs alike.

I encountered it playing Vernharl and Hastur especially, Hastur in the pivotal Passion checks that resulted in his decision not to harm Darrald and not to strike at Vernharl in the climactic melee. Unfortunately, he didn’t get much of a chance to develop in response to those decisions, but the Bounce as applied to Intent forced me to reevaluate his entire makeup: I was left wondering “Who the fuck is this guy?” in the best possible way.

Vernharl’s Passion checks led to such rich fictional content, and the effects of Fanaticism, cast on him by Narmeed, were key to the results of the final melee. (It’s worth noting that additional Bounce can be added to Intent when Spirit Magic comes into play. Once Demoralizes and Fanaticisms are zinging back and forth, a character might not have a say in whether she pursues or abandons a combat.)

The Bounce added by Passions was a constant delight in playing the GMPCs, and I am overall very happy with how I played Vernharl. I must admit I am disappointed in myself for deciding to leave his final feelings toward Hastur up to the Passion dice. In retrospect, this feels like a copout to avoid tough thematic questions, for the exact reasons you outline above. The character had presented “I do this,” to me, and I think my responsibility was to ask “having done it, was it right or not, so what do you do now?”

There’s one other variable here I should probably mention: Narmeed’s lack of Lore skills. I bring it up because Cult Lore (Storm Bull) would probably have been Narmeed’s primary interface with the beliefs of his cult, considering he was the most senior Storm Bull in the situation. It would have been used to delve into Storm Bull secrets and reinterpret existing understandings. Without it, Narmeed had to do his best with the knowledge available.

I bring it up because I felt similarly constrained (in both the everyday and the Adept-Play senses of the word) while playing sweet, dull and dangerous Theoxxa Ag in Whimsical Ways. I had to manage a new, wildly weird and wonderful setting while seeing that setting through the green cat-eyes of a PC who missed a lot of what was happening around her.

In that position, I personally found myself playing more reactively, being a bit more cautious, and reserving judgments and stances on characters, even as I tried to play my character true to her volatile nature. I left Whimsical Ways feeling that I have a lot to learn about riding comets!

To return to Narmeed, the Divination ceremony in Session 11 seems to me one of the most pivotal scenes in the game in this regard, and Narmeed’s failed Divination checks within it some of the most important rolls of our game. My buddy got to bring his moral stance on Storm Bull into play, and those failures solidified that his character wouldn’t arrive at a deeper understanding of his own ethics or his cult’s morality.

The player presented “What about this?” to the character and the character came back with “No, I don’t get it, so what do I do now?”

I must admit I am

This is discussable. If one plays roll to roll to roll, effectively taking stage directions submissively (“professionally” perhaps), then you’re not playing. You’re acting.

It's a good time to review the concept of agency. If someone else were playing the character as summarized on the sheet, and if all the rolls went exactly the same way, then how would play be any different? Does it matter that you are the person playing this character (or playing anything; this concept applies to anyone with any authorities at all), as opposed to anyone else? Or do you have the same “one job” that anyone else would have, to roll to hit or do-this-do-that when directed to do so, either by GM’s signal or, in this case, by the dice?

What happens in play between Passion-dependent and Trait-dependent moments? What do you do (or does anyone do) which sets up a given behavior-affecting roll, as opposed to some other Passion or some other Trait pair? And, how much activity does a given outcomeof this kind determine: just for the next roll, after which there is some non-dice-directed latitude, or the character’s attitude and understanding throughout play until another roll comes along?

Trait rules

This is an extensive footnote to our conversation above, in two parts.

Part 1

Pendragon, which provided this aspect of RQG’s design, leans far into “players play as directed,” with rolls providing the important forks and moments of the eventual plot. The published adventures are so programmed that all the potential eventual plots can be laid out in lovely mind-maps, easily drawn upon a single reading. The game text also states outright how the GM, backdrop, and players are configured, with the players in a decidedly subordinate, “this happens, feeeeel it, now this happens” position.

Now, I have not played Pendragon to any extent that I can trust about this issue. So I don’t know whether, and how, and with who as actual players, it does not play as a canned & planned “choose your own adventure” with rolls at the choices. I do know that it would depend on whether those personal actions and behaviors between behavior-affecting rolls interplay with the rolls (so both are good, but only as they interrelate). If that interplay is consequential, then the rolled-behavior outcomes act as powerful surges and swerves – fuel for who the knights are, or for realizations of their real range of action compared to their ideals. If it isn’t, then, well, you’re here to act out what you’ve been directed to do.

Brief clarification: I hope you can see that I am not talking about so-called free play, where resolutions occur without rolls for a while, then we shift into some mode of play when we do all our resolutions with rolls, in a switchback fashion.

Savage swerve (one paragraph only): Bluntly, at least some of the early Chaosium designers did strongly favor nearly-automatic play, in the interest of plug-and-play, out-of-the-box, one-shot-demo fun. Based on my conversations with them, this general dismissal of the players as individuals tracked what was apparently complete ignorance among the players they’d encountered regarding actual mythology, classical or fantasy literature, or playing a character as anything but a goofy avatar. They accepted that most, nigh-all players were illiterate, could participate only as audience, and might learn at least a little bit about Malory, Lovecraft, or non-Christian myth via playing, with an RPG session as their first contact with these things.

Part 2

I’d like to know whether a particular feature of the Traits in Pendragon has or has not been expressed in RGQ. They come into play in either of two ways, which differ greatly from one another.

The trouble is that I have rarely encountered anyone who seems to understand this, so I am bravely forging ahead with this part of the footnote although I know it may cause cries of “you don’t understand” and “actually” originating from either of the two ways.

If the Trait is 16 or over, then you have to use Way #2 in any relevant situation, i.e., you can only behave off-preference if the dice let you. That said, Way #2 is a little less deterministic than I described above insofar as the roll might put you at “failure” for either option (I won’t go into the procedural details), in which case it’s thrown into the player’s hands, i.e., the dice said “you decide.” So there’s some Way #1 buried in Way #2, sometimes.

The text acknowledges that part of Way #2 includes the player being “hit” by the GM with involuntary behavior and encourages not getting into situations which would result in that, if you don’t want it. However, I think it’s clear to anyone that avoiding such situations successfully is pretty much a non-starter for this game. The only ways to avoid getting “hit” like that (again, assuming you don’t want it) is to use Way #1 assertively enough to pre-empt the GM from doing Way #2 on you, or not to play this game.

So here’s my question: do the Trait (Rune) rules in RQG include Way #1 at all? From your account of play, clearly you and your play partner utilized Way #2 about as hard and often as anyone could be expected to do. (See Wuthering Heights as a similar play-experience, albeit for comedy.) If Way #1 is present in the rules, did you or your partner know about it?

This is discussable. If one

My whole response should be read in light of my growing understanding of how wide-open a single roll in RQG can be.

Yes, it absolutely matters who is playing the character.

Just as with Traits in Pendragon: “if the Passion/Rune is 80% (16*5) or over, then you have to use Way #2 in any relevant situation, i.e., you can only behave off-preference if the dice let you.” The obverse of this is that the events that trigger under-80% Passion rolls are entirely up to the player. Someone else playing Vernharl would have seen different opportunities to trigger the mechanics, or used different Runes/Passions. I decided to go to the Passion dice to find out Vernharl’s feelings regarding his actions toward Hastur; someone else may have said “It’s clear to me that Vernharl isn’t too broken up/is really fucked up over it” and played accordingly.

In the absence of pre-scripted triggers and railroaded events, it’s hard for me to imagine the Passion rolls being so deterministic that they lead to “acting, not playing.”

However, I want to go one step further here and say that even if the same Passion rolls were triggered by the same events at the same points in the fiction, different players at the helm would mean very different outcomes (with the proviso that we are playing, not acting).

This is because “how and why they triggered/didn’t trigger the Passion, what a triggered/untriggered roll makes possible or impossible, and exactly how long a particular Passion/Rune roll holds true are all wide-open questions.” I decided that Vernharl’s final Passion roll would apply long-term, reflecting whether or not Vernharl could shake off Hastur’s ghost. Someone else may have given this roll a narrower scope (giving Narmeed a chance to address Vernharl’s feelings later, for instance).

Again, so long as Passion rolls are made in the context of real play, I don’t see a way that they could be used to merely “act” the character instead of playing them.

This is actually enormously helpful in clarifying the rules to myself! The role occupied by Traits in Pendragon seems to have been taken up by Power and Form Runes in RQG: Instead of Lustful::Chaste, characters have Fertility::Death (the Elemental Runes work a bit differently and are not in opposed pairs). On a failed Inspiration, Rune Magic or Rune check roll, you roll on the opposite Rune, possibly creating constraints on the character’s action and racking up an opposing check.

(If memory of reading Pendragon serves, RQG’s concept of a “Magical Test”—where, for instance, “a sword might only be wielded by someone strong in the Death Rune”—is a Gloranthan application of Pendragon Traits.)

Yes, way #1 is present in the rules. The “Runes” chapter states that “The gamemaster may decide that an action performed by an adventurer deserves an experience check for a Rune. It may not always be because of a roll against a Rune.”

We leveraged this option for Runes; also (I’m now realizing this isn’t RAW) for Passions. When Narmeed took a season to train the Dagger-Skull Boys, they got checks in their weapons skills and their Loyalty (Narmeed) passion. We did see Narmeed’s Runes “creeping to values and stabilizing pretty much with how he was behaving.”

As I noted above, once a character’s Passion hits 80% or more, they are open to more intrusive calls from that Passion (the dice are required, as in Pendragon). They can straight-up refuse to roll against a Passion, but at the cost of reducing the Passion to any number below 80% at the GM’s discretion. Many cults have 80%+ requirements for Rune-level status, so this decision could result in the temporary loss of Rune-level benefits.

(One thing I only just noticed is that you can also oppose a Rune with a relevant Passion…if a conflict comes down to your loyalty to your temple or a loved one, I guess you better have a high Love (Individual) passion to give you a bit more control over your character.)

And this is interesting, in light of your observations regarding “nearly-automatic play.” The “Passions” chapter clearly states that “Runes and Passions with a rating of 80% or higher can place your adventurer at the mercy of the gamemaster.” The “Runes” chapter only says that “A test of conflicting Runes may be imposed by the gamemaster.”

The chapter only uses Runes over 80% in the examples. However, it does not explicitly state that only Runes over 80% can be invoked to determine behavior, and the examples are a lot murkier about whether it’s the player or the GM calling on the PC’s Runes. There’s an additional option given for Runes too. As well as just reducing it to a number below 80%, the GM can knock off 1d10% when a player decides to ignore an imposed Rune conflict.

At first I thought this was a lack of clarity, and figured mandatory Rune checks should be made using the same procedures as Passions, i.e., only at 80% or more. Now, I think it’s likely a deliberate ambiguity that leaves the door open for ‘’’’play’’’’ (imagine dozens more quotation marks around that term) where every character is basically a Rune-automaton. The players get to program their little LEGO Mindstorms constructs, then set them ‘free’ on the GM’s course to bump against the obstacles and each other.

One could imagine the -1d10% option as presented to the exhausted GM, put-upon by rebellious players determined to play their characters their way, as a time-saving device so they don’t have to evaluate how much % a given action warrants subtracting from the Rune. They can give the player's knuckles a sharp rap and get everyone back on course to the Story. Oof, it’s a particularly dispiriting realization because of how powerful these mechanics can be in the context of real play.

Had to include this: I see exactly what you are saying. That “switchback” conception makes as little sense as believing that ‘roleplaying’ (the creative medium we work in) gets boxed and packed away once we break out the conflict resolution procedures, and that ‘lite’ conflict resolution systems will therefore lead to deeper roleplaying than was possible in the “bad old games.”

I can’t tell whether you’re

I can't tell whether you're agreeing, disagreeing, or combining bits of each. There are some clear parts and unclear parts as well.

Just to back it up so I can understand what happened in play, and not to frame this in any way about whether you were doing "real play" or not (that is not in dispute), here are some questions about what I don't know. They are applied specifically about Narmeed, for a few reasons, one of which is simplicity.

Quick fairness check: I think these are probably unanswerable in this venue, and I don't expect answers or even really want them. As public statements they are too close to certain kinds of self-criticism that I don't want anyone to do. My goal is to model the kinds of questions I bring to this or any similar system.

When was Rune (Trait) relevant behavior conducted as Way #1? Well, rather than comb 12 sessions, let me put this way, how often was Way #1 used relative to Way #2, when eligible?

Shoot, I even have questions about my own question. I don't know Narmeed's scores, so I don't even know if he had Runes less extreme than 80/20. So my question only applies if he did, i.e., 75/25 and middling from there, and if circumstances of play ever saw him behaving relevant to those pairs. I think your account means that in those cases, your play partner did not roll but rather just said what Narmeed did and took a relevant check for it, but I'm not sure.

How did your play partner typically apply the results of Way #2, in terms of intensity and duration of the emotional or thematic direction indicated by the dice, as opposed to Way #1 (when and if it was used)? My implication here is that one might tend to apply dice-y-directed effects harder and longer than "I say what he does" effects, even though the rules treat them equivalently.

Again, offered as system thoughts rather than an interrogation. We can take some of it to voice some time, for some questions that help me understand the sheet and events of play better.

Just to back it up so I can

Love this. In the interest of clarifying my orientation toward your thoughts in the previous comments, I am going to dip my left big toe, no more, into the dark waters of “I meant…I understood you to say…”

<orienting>

I am in total agreement with your observations regarding the system. Before reading your comment, I hadn’t considered the possibility of using Passions and Runes as tools of “nearly-automatic play.” So my thoughts above are tracing the way we used the rules (in the context of genuine play), and also contrasting that with (how I imagine one would) use the Runes in the other, “nearly-automatic” context.

I emphasized the instances of “I decided” in order to address your question “If someone else were playing the character as summarized on the sheet, and if all the rolls went exactly the same way, then how would play be any different?” Those (and similar statements) were intended to focus in on how me being in control of Vernharl made a significant difference to what happened, not be defensive gestures. I know and trust you enough to interpet your statements with a maximum of good will, and I’m well aware you weren’t calling our play into question. Any comment from me that comes off as self-critical should be read in light of how successful the game was for us and that we had so much fun we’re doing the whole thing again.

</orienting>

These answers are fairly easy.

Narmeed pretty much used Way #1 exclusively, with me and my fellow player suggesting checks where it became relevant. His only Rune over 80% was Death. As you can well imagine, most opportunities for mandatory Personality Conflict checks on the Rune were rendered moot by my fellow player playing Narmeed in a scary, Deathly fashion. Mostly, he played Narmeed as he saw fit and accumulated checks as he went

I used Way #2 all over the place for Vernharl, Hastur and Willandring. All of these instances were technically “non-mandatory” as none of these characters had Passions or Runes over 80%.

I'd love to discuss the nuances of these rules over voice if you want to go into more detail. My attention has been pretty evenly divided between actually answering your questions and making sense, to myself, of the various ways we used these rules.