We started a Worlds Without Number (WWN) game, playing in-person.

WWN is built on the chassis of various editions, rememberings, and reconfigurations of the pre-3rd edition non-Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. It turns the dial up on Vancianisms, mostly through spell names and spell powers (spells are more versatile and powerful than spells in, say, Moldvay Basic, but spellcasters get fewer of them). It also gives non-spell powers to Mages, which are able to be used by Committing a resource called Effort for a certain duration: a turn, a scene, or all day. Squint (or don’t, even) and it looks like At-Wills, Encounters, and Dailies from 4e or Short-Rest/Long-Rest abilities from 5e.

There are four classes in the game: Warrior, Expert, Mage, and Adventurer. The latter allows you to take two partial classes, splitting up the previous three into various combinations. The game has some nifty healing rules that I like, too, and oh, I don’t need to detail it all here, but you know: it’s one of those games: it gets called OSR. Its most salient feature is really not about procedures or mechanics that turn the gears during play itself, but about how it supports prep: there are a lot of good tools for creating dynamic places pregnant with crisis for all sorts of reasons.

I have a bunch of awesome modules laying around, some favorite rules tweaks, and ideas and excitement about a far far future dying earth; and I knew some people who were interested in the game. So I decided to run it.

I knew for a game like this I’d want to take some time to really get prepared; I wanted to make sure I felt comfortable with the rules and with the starting situation. So I declared in June that I’d begin running the game in August, and started my prep. That sounds like a long time, and I suppose it is, but I enjoyed not having any pressure to prep. I read the rulebook twice, I followed the preparation procedures, and I let myself noodle and dream and steal ideas from all sorts of places. And I drew two maps! I’ve never done that before. It was fun and the visuals really drew potential players in, I think.

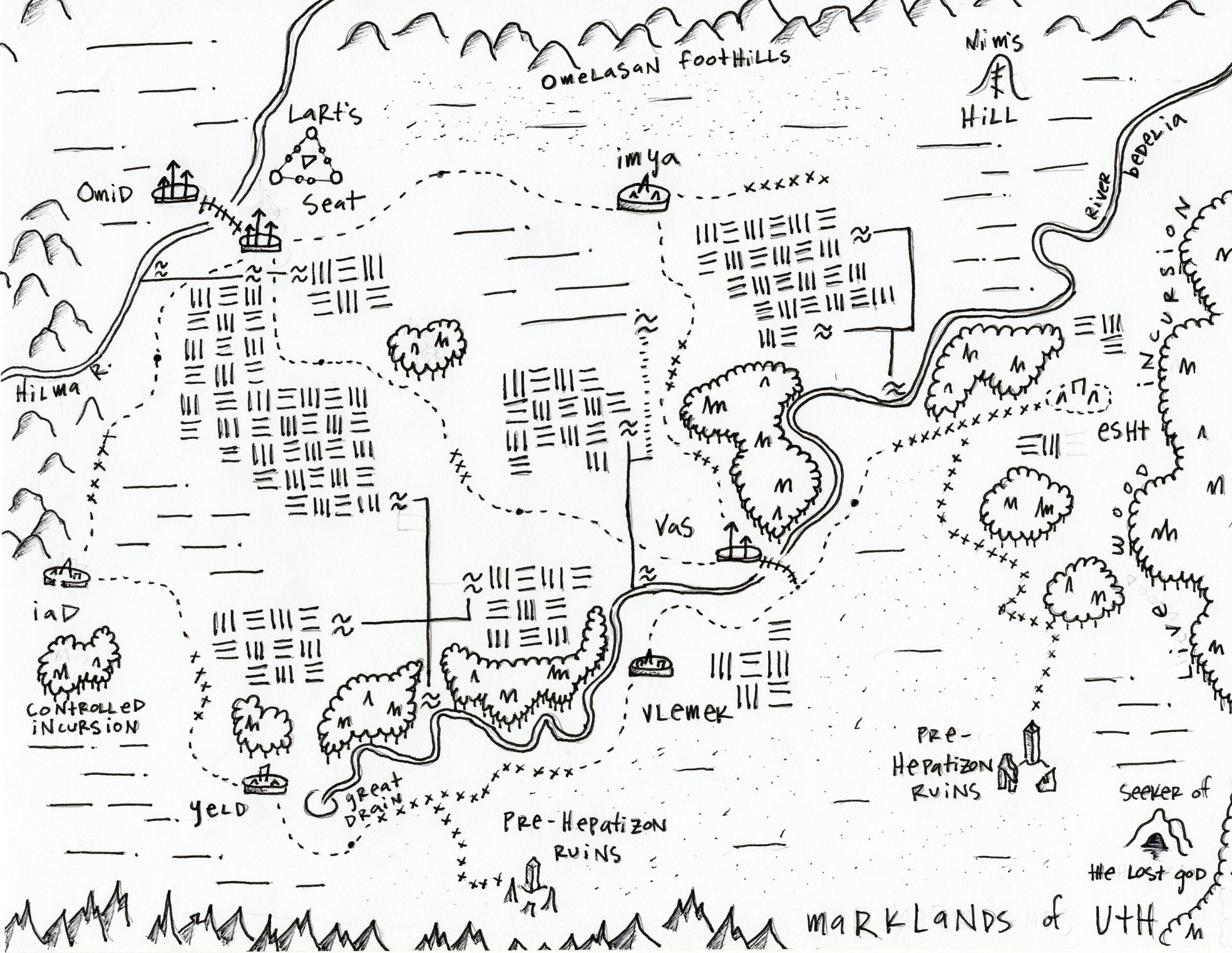

The header image is the larger region of play, with each of those icons essentially fleshed out in a large sense: who lives there, what their society and/or religion is like, what they think about the other groups in the area, what they want from the other groups in the area, noodlings from me about possible areas of interest and danger, etc. Around a hundred years ago, the Immortal Reaping King, who conquered this whole peninsula, mysteriously disappeared (he lived up at the top, where it says “Folding Palace”)

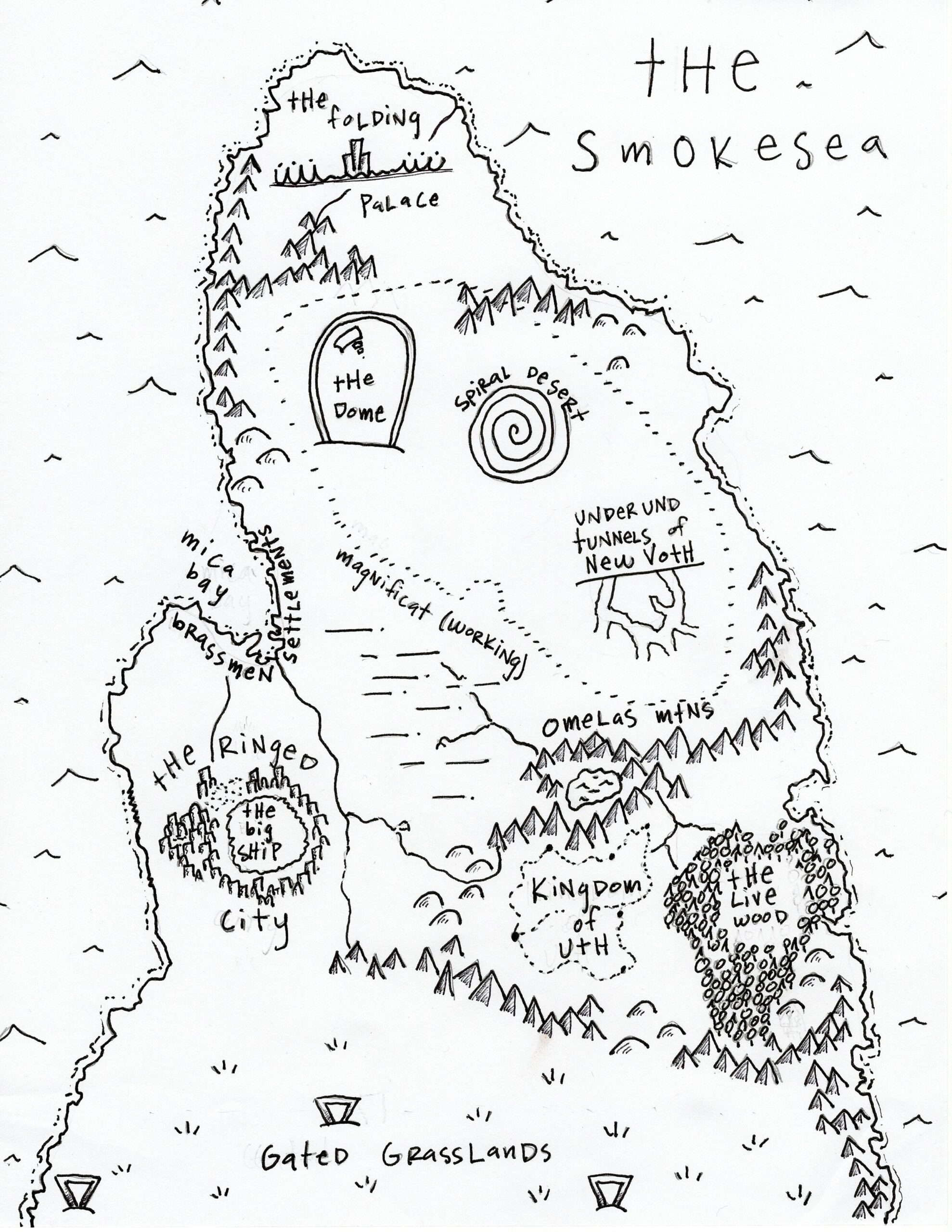

This is the map of the starting section of the region. This used to be a place of squabbling petty warlords, but around fifty years ago, two things converged that have made it the place it is today (a largely thriving feudal land that is just beginning to recognize its own statehood, and what that might mean): The nobles who lived around the Folding Palace, no longer getting any tribute from anywhere in the region after the Reaping King left, began to filter throughout the region, and many settled here: it’s temperate, and Uth the Lart (his title) allowed them to buy nobility, making his burgeoning state flush with cash. And also, around this time, Uth procured (somehow, from somewhere; rumors abound) what are known as the Calibres: ten incredibly powerful, frightening hand-held weapons that allow one to kill a man just by moving their finger. With these he was able to consolidate and hold power over what are now known as the Marklands, after his nobility, known as “Marks”.

This is the map of the starting section of the region. This used to be a place of squabbling petty warlords, but around fifty years ago, two things converged that have made it the place it is today (a largely thriving feudal land that is just beginning to recognize its own statehood, and what that might mean): The nobles who lived around the Folding Palace, no longer getting any tribute from anywhere in the region after the Reaping King left, began to filter throughout the region, and many settled here: it’s temperate, and Uth the Lart (his title) allowed them to buy nobility, making his burgeoning state flush with cash. And also, around this time, Uth procured (somehow, from somewhere; rumors abound) what are known as the Calibres: ten incredibly powerful, frightening hand-held weapons that allow one to kill a man just by moving their finger. With these he was able to consolidate and hold power over what are now known as the Marklands, after his nobility, known as “Marks”.

He has nine Valiants that attend him at all times, except when he sends them off, singly or in groups, on business. They are the highest authorities in the land below him, but are outside of the Mark hierarchy. They hold office due to wielding one of the Calibres. It is the station of office and the right to it. If you possess the Calibre, you own it. If you own it, you own the office of Valiant, along with its attendant ceremonial (and very practical) armor, as well as the right to ride a Courser for a mount, a lion-like, horse-sized creature that is incredibly expensive and dangerous to break, train, and maintain.

That’s a lot of backstory-dump, but it was essentially what I described to the players as they made characters and formed the group, so it provides context for anyone following along. We have three characters, all from the town of Imya, which is where the military (really just semi-organized groups of men-at-arms) is headquartered:

Demetri, a Warrior, who got into a street altercation as a kid and accidentally killed a person; his fists are deadly, and this was his first lesson. He had a choice: get shipped off to the dungeon-prison beneath Omid, or serve for two years as a man-at-arms. He did, and now his term is up.

Background: Soldier.

Ambition: Prove to people that I can be a hero, so that they’ll see me for who I really am, not for what I’ve done.

Torix, a Warrior/Expert, who knows a thing or two about how to keep books and how to recognize quality goods. He dealt goods and arms to the burgeoning military, skimming off the top quite successfully for a while, until someone caught him and gave him an ultimatum: find a MacGuffin (“something you can put in a dungeon somewhere” is a paraphrase of what his player said”) for me, or I’ll rat you out.

Background: Criminal.

Ambition: find the MacGuffin.

Fincules, a Mage/Expert, who is a bit of a man-about-town, a gregarious face who knows how to sell, and oversell, his goods. He may provide you something magical, or he may just say it’s magical — not to grift you, but just because he wants you to know how impressive he is.

Background: Merchant.

Ambition: Fame.

Fincules is the linchpin of the character group, keeping an eye on Demetri and using him for odd jobs and bodyguarding. Both he and Torix know a thing or two about shady business deals, and in that world you can’t help but cross paths. As play starts they all find themselves broke, wondering what is next in life, and in the middle of a couple rumors.

As the Marklands becomes more stable, and wealthy, there are increasing incursions into the Omelas Mountains, which is crawling with toughened mountain people and warlords, but is also home to untold lost magical civilizations carved out under those mountains. Having some magical knowledge, Fincules has heard a rumor about a mage who used to come around here nigh fifty years ago, doing research into the Live Wood (a dangerous feature of the landscape that seems to secrete monsters and has to constantly be chopped down, only to grow back very quickly). He hasn’t been heard of since then, but he does (did?) have a tower in the Omelasan Foothills, often surrounded by lightning, which can be seen on extremely clear days.

The other thing they heard was that one of the Valiants was on his way to Imya (it had been announced in advance, and everyone was very much looking forward to it/fearing it) when he veered south off the road into a section of the Live Wood. That night, the report of his weapon was heard for miles around. Then he wasn’t seen again.

The players opted to go check out the Mage’s tower, with Fincules being the primary instigator in this regard: it’s gotta have treasure, right? And treasure = fame, right? So off they go, but not before we pause a bit for them to ensure they have food and water.

At this point I tent a 3×5 card and put it on the table and write the following on it: “Find out what’s interesting/valuable in the Tower — 3xp, 1 renown.”

WWN doesn’t define how XP is earned, but instead throws out options: XP for Gold, XP for showing up (blegh), XP for completing Goals, etc. I went with a modified version of the latter option, defining Goals as group goals — any option for adventuring I might give the group will get an XP value attached to it, and they can pursue it or not. Or any particular goal they define for themselves will get an XP value attached to it. And then whatever they pursue is what they pursue. Also, each character has a broad Ambition, and if they can reasonably be said to be aiming in its direction during a session of play, they get 1XP.

I realize now that I forgot to assign and communicate an XP value to the second option for what to pursue today, finding the Valiant. So I should do that at the beginning of next session, just so they are aware of the options and what’s at stake.

3xp is enough to get to 2nd level, and Renown is a sub-system that lets players spend their fame and social capital to undertake major projects (establish an educational institution, a religious order, turn a town into a trading hub, etc). I’ve opted to attach Renown to the group Goals, as well, with the caveat that while XP will always be what is written (i.e., as a judgement of difficulty it may be off, but whether the Goal is easier or harder than expected, you’ll get the XP written), Renown may fluctuate from what is written depending on what is actually done and then communicated in civilization, with it being far likelier that the group will acquire more Renown than what is written than less.

After they got their food and water, Torix wanted to look through old piles of surveying documents and see if he could find some sort of clear path to this tower, or any information about it. He failed his skill roll, and I botched the description of his failure, stating that he found a little bit of old information about a trail, but it may or may not be useful these days. It dead-ended that inquiry instead of opening it up. In retrospect, it would have been better to say that no, he didn’t find anything useful, but someone found out that he was poking around and was willing to sell him access to some useful documents. Or something. Anything more useful for play than simply, “no”. I established before play that the “intent and task” rules from Burning Wheel are in effect in this game, as I find that separating intent and task when it comes to skill rolls in task-based d&d-likes heads a lot of problems off at the pass and tends to ground skill action in the fiction better. But in this case, it didn’t save me from my own creative failure (I’m belaboring this, but I don’t mean to make it a big deal: the ball got tossed to me and I flubbed it a little bit, that’s all–but I wanted to pull that interaction apart).

In the middle of high summer they headed off through grasslands and scrub, toward the tower. They had four days of pleasant journeying, with Fincules eating far too much of his share of the food and Torix running out of water (Usage Dice from the Black Hack are in effect here, replacing consumable items with a die that gets rolled on each use and steps down the die chain on a 1 or 2, until eventually you’re out).

They had gotten into the hills now, bare scrub hills that look like bald brown heads, and had to spend half of each day foraging for water. They see the top of the tower way off, a glint of metal, and lightning flashing down to it every so often. No one had chosen Survive as a skill, so they were rolling at a heavy disadvantage to find food or water, and were only able to scrape together a little bit of water for the rest of the trip. They haven’t suffered any System Strain yet, but they are low on everything.

Finally, as the end of the sixth day comes, they scale a small hill and see a large stone tower, capped with a bulb half made of the stone and part of the rest of the tower, with the top half made of interlocking metal plates with spikes sticking up off the plates. Lightning is hitting these spikes often, and hitting four large spikes in the ground around the tower. The rest of the ground around the tower has been pulverized into fine moonlike dust over the years.

Okay, so, then, it’s time to end the session. We’ve actually gone a bit over time; it’s clear that we’re all digging this.

One of the players turns to me and says, “Is this Tower of the Stargazer?” That’s a Lamentations of the Flame Princess module, and it’s indeed the module I’m using as the basis for this particular tower, with a few small tweaks. I hesitated; I didn’t know what to say. Bizarrely, I considered lying for a second. Then I said that yeah, it was. He said that he had run that before.

I felt instantly deflated. I kind of felt accused, though not by the player (he clearly was doing nothing other than being honest and trying to help head off a bad play situation waiting for all of us in our near future); it was as if I had failed, somehow, in my prep, though of course I hadn’t. It took me a couple hours after that to really get over it, poring through some things on my shelves, googling other Wizard’s Tower adventures that could fit the fiction we had established and that I was interested in presenting. I’m all good now; I have something that I’m excited about, and it was merely a hiccup (other than a couple hours of prep time that I can’t use). But in emotional terms my reaction to that moment was quite strong.

To make what I’m running next time fit, I will have to change one detail about the Tower as previously established–it had no windows, but it will have to have some next time–but that’s relatively minor.

11 responses to “Beginnings of a Bricolage”

Ooh, maps!

What great maps, and what evocative prep — I love the Valiants and the Calibres (and the implications of someone aspiring to get a hold of one). I'm curious if you can say a little more about how the game supports this kind of prep — for instance, are you rolling on random tables to develop a region, like you would make a Subsector in Traveller? How much of the weird, evocative fantasy feel do you think comes out of the encounter with the game's procedures, and how much is your own personal bug juice (to borrow a phrase from Ron)?

Yes, let’s talk about prep!

Yes, let's talk about prep!

There are a lot of random tables, guided by procedure. For "building a campaign", you start at the region level, following procedures like Choose about six major geographical features and Create six nations or groups of importance and Assign two important historal events to each group or nation.

Each of these procedural points has corresponding tables and further advice and/or procedures. I did start with quite a bit of "bug juice", for example, I had a lot of nations/groups of importance already swirling about my brain, so I didn't need to roll on the "nation theme" table to create them, but I did take my initial juice and roll on that table to develop them, then roll on tables to create the aforementioned historical events, which helped me develop the ties between the groups. The geographical features table certainly shaped the physical space all this is happening in.

After the region level, you move to the "kingdom level", or where the campaign is going to start. You Flesh out its history by rolling on more tables to develop the historical events already rolled in the previous step, Identify the rulers and their enemies, Choose one or more problems or goals the kingdom is facing, etc. I already knew the ruler: Uth the Lart and his Valiants and the Calibres and all that was pure bug juice, but the tables helped me identify enemies, pulling in stuff generated at the regional level (that bit about the Reaping King's nobles coming in and buying their way to power in Uth's nascent society) and making it more concrete, creating inter- and intra-faction squabbling.

I had a lot of material at this point, but not a lot that would focus the first session of play, so I drilled down to the level of a town and rolled rolled on the Community Tags table — you roll twice and mash two tags together to create the character of this community. Tags are things like Dueling Lords, Fallen Prosperity, Magical Academy, Toxic Economy. Each tag then has five further elements to it that can be used as inspiration: Enemies, Friends, Complications, Things, and Places. And each of those five elements has three options. So the Place section for Toxic Economy says: "Pesthouse full of the cripppled, Splendid mansion built off the product's profits, Factory full of lethal fumes and effects."

I can't remember which tags I rolled for Imya, but rolling those established that this is the seat of the nation's military (such as it is) and also a hotbed for feuding between the native Lartans of the area and those Reaping King nobles who are increasingly influential. The military bit definitely influenced the character and group creation; the latter didn't, as I didn't mention it (there were a lot of things going on and it didn't seem relevant to interject with that at any point; if they spend any time in the city it'll be apparent).

There are tables for creating ruins and places of interest, tables for creating Combat, Exploration, Investigation, and Social Challenges. I didn't use any of these, because I had two modules ready to go as options for play, as described in the post.

To answer your last question more directly, I think a lot of the weird, evocative fantasy feel is bug juice, with some of that juice pilfered from the setting as described in the book and mixed into my own particular cocktail (there's no "canon", but the book does detail a region, presumably as an example of what the procedures have created). But the procedures help form what spark I've brought to the book and focus it on playable stuff (or at least that's how it seems to me so far).

Been There

So I felt this a bit too

It is one of the issues we run into running adventures that have been around a while or have a wide audience. As a player I try to be honest if I haev played something before, but make it clear I am happy to "play dumb" for the session. I mean I'd happily run through any number of Basic or Expert modules folks want to run and never utter a word.

But as a GM I do think about it, though less about content and more about "are they judging me on how I run this?" Which is unfair; who doesn't think about how they would run content different than it is being run for them? It can be hard enough not to feel self-conscious at times, so I try to not worry about it too much.

WWN is on my watch list and this has been a great rundown. Thanks for sharing it.

There also is this whole

There also is this whole content-machine on the internet about showing and reviewing the newest coolest module, so I think a lot of people are also consuming these, in whole or in part, in review or in actual (reading), because they are following the OSR scene and are planning to maybe one day run X or cobble something together from Y and Z, so there's a familiarity that comes even if people haven't run things themselves.

And, of course, there are modules that are widely popular and get run a lot; in these latter days running Tower is not too far from running something like Keep on the Borderlands–if I had thought about it, I might have thought twice. I'm trying not to worry about it too much, though. The player who said he recognized Tower also looked at my shelf of Lamentations adventures and Hot Springs Island and a few other things and said that he had read or run all of those, too. Some of which I had half-planned to stick somewhere. So that was an additional bummer in the moment, but I have other things, and I am interested in also doing my own prep/development for locations. I hadn't considered your response of just running it anyway and maybe kinda dealing with how they are thinking and responding. That's of course reasonable, too, when it comes to the real-world concerns of play.

I want to get deeper into

I want to get deeper into this issue. I think topics like "what to do when your players know the module," or the emotional issue of betrayal or disappointment in full knowledge that the player isn't doing anything bad, or similar, are not trivial, but they all overlook the basic operating concern.

Which is: non-uniform starting information is a critical variable of play. I guess I should clarify that I'm referring to information known to real persons, never mind the characters, as that is a different issue.

By "variable," I mean it can be organized in many different ways. The range includes total uniformity at one end and total non-uniformity at the other, which are both imaginable at least for certain moments of play. In between is a wild spectrum or even constellation of possible starting, developing, and transitional arrangements of who knows what.

By "critical," I mean that however information is distributed around the real people at the outset, or for some later point in play, or for this game in general, its conformation is integrated with any and all of the game's other procedures. Without it, one of the core features of playable content at all – uncertainty – is gone, or at the very least thrown into a different conformation which doesn't go well with everything else we're doing. Different games or groups arrive at uncertainty about what differently, but it has to be there.

That's why I can put intentions and feelings aside and say that yes, it really is a "thing" or problem when one person is supposed to know X and Y and Z, and the others aren't supposed to, and it turns out that someone does. Basically: play won't work. Something does indeed have to be done – not because anyone did a bad thing, not because of egos and emotions and social contracts – but because the threat to play is totally and practically true.

[Side point: it may be surprising to encounter a group or a game in which information is distributed differently from how you expect, and for which it still works. I've played lots of map-based combat or exploration with the map open on the table, because for those games, uncertainty about things the characters couldn't see wasn't a critical issue. It's a bit startling to people who have only encountered maps of this sort as a specific kind of uncertainty. My point, however, is that these people are not generally wrong or naive, because there are definitely games for which that would not be functional. And no roleplaying operates without uncertainty of some kind.]

The big wrinkle is publication, and perhaps, the very idea that a published scenario or situation for play is modular – geez, the more I think about it, the more alarming that word becomes. Modularity means you slot it in, as is, and I think as used in the hobby, it also implies or expects that the whole experience of play will be provided by this … lozenge, or ammunition clip, or, well, module.

If we believe that, collectively, then I could easily understand having the exact same emotional response that you describe, Hans, experienced as guilt, and I would also understand never, ever venturing into GM-only tagged textual material except when taking on that role. However, that expectation is flatly nuts. Play isn't modular in that fashion, and most of the ills of this activity, historically and today, arise from expecting it to be.

When I've provided content for "scenarios" for other publishers' games, I've always run into trouble from the editors and publishers. They always perceive the work as incomplete because it has no provisions for what will happen "halfway through." Even providing Bangs which may occur during play isn't good enough, because they want to be certain about what will happen due to those Bangs. Multiple outcomes are fine but they have to be fixed and known, not merely example of could-be's.

In my own work, if you have the annotated Sorcerer, you can see my thoughts on how badly the "starting scenario" backfired over the years, as people read it as a standard Call of Cthulhu module. I can see why they did that. The same problem applies to the detailed scenarios in The Sorcerer's Soul, for which nothing I could say could break the reader's identification of detailed/deep backstory with controlled/managed outcomes of play. Sorcerer & Sword, Sex & Sorcery, and Trollbabe represent different steps in breaking it more effectively.

Perhaps that leads to a practical point: that any published adventure, scenario, whatever-we-call-it material cannot be reasonably considered actually to be modular. Lots of possible discussions proceed from here.

Ron, I think we had a chat on

Ron, I think we had a chat on this subject on Discord, but I don't remember if it was recorded or not.

I think it started with me asking "Can there ever be a published module or adventure that is good for play? If so, what features should it have?". I'm not particularly optimistic, but I had a number of positive experiences using published materials, and I'm still very interested in understanding if this is just a manifestation of the well known "unplayable stuff becomes playable because players fix it" phenomenon or if there is an actually discernible list of features that are positive and usable on their own merits in these products.

I have an example that may be precisely the kind of thing you're talking about: 4 or 5 years ago a ran a fairly long game of Warhammer Fantasy. We were using 3rd edition, which is an "odd" edition for the game because it radically changes the rules and procedures. When we started play I was in fairly busy time of my life and I decided to rely heavily on the few (and extremely expensive) published modules. Several of them set out to do exactly what you're describing here: be "modular" and even playable more than once or with people who already know the product – obviously according to the people selling you the books.

One of these modules is particularly explicit (and dare I say proud) about the solution: called "The Enemy Within" (referencing the much more famous and well loved 2nd edition mega-adventure), it's a giant whodunnit about an high profile imperial personality being secretly a chaos cultist.

How do you keep a conspiracy fresh if someone already read or played the adventure? The authors choose this approach: you have four major NPCs, and the DM picks which one is the cultist at the beginning of the game. You have small boxes telling you "If XXX is the villain, modify this and this" across the book but let's say the script for the adventure encourages the players to suspect any of them, with reason. The authors seem to acknowledge this by saying that having more than one of the suspects be into the conspiracy works even better.

Obviously this is cute and all and also completely unplayable. Played as written, the module expects you to drag along the players across a set of events that need to happen no matter what. Their only agency is figuring out who the bad guy is – and not matter when they do, they can only really stop the conspiracy in one big climax happening in the capital. They can't really stop it from happening, or steer the story in any way.

So it's terrible, right?

Not completely, because all of what I'm sure the authors considered "distractions" or red herrings turned out to be playable for my group and useful to me as a DM.

The game opens with a series of murders – quite literally the players witness the rise of a serial killer in their local community. WFRPG 3rd edition hinges on "professions" rather than "classes", meaning that a character's social role (merchant, magistrate, town champion, rat catcher or whatnot) is always identified and ready for use. The book asks you to insert the players in the context of the starting town as people who lived and worked there for a number of years, and by the second day my players had absolutely ignored the first murders and focused on setting up a print shop, buying real estate, reinforcing their smuggling business and trying to seduce a local noble. The book is smart enough to invite and encourage that players focus on their own personal and daily matters, and it took us 3 sessions before the 4th murder happened and someone they grew close to was the victim. At this point, they cared enough to go and somewhat follow the threads of the "plot" while still caring mostly about the things they had set in motion.

Over time, we ended up loosely following the thread of some conspiracy happening in the background, but group had their own nascent gang of religiously righteous criminals led by a sigmarite priest and a disgraced town magistrate to tend to. Fighting the conspiracy was a way to preserve their business and only happened when the things that happened in the background (something that in other games would be "tripwires" or "clocks for fronts") got in their way. I easily managed to insert the other modules – a few are legitimately great, expecially one called The Gathering Storm, involving a town with its own troubles that is going under the weather (literally) because a few unrelated actors have stolen pieces of an ancient eleven stone nearby. It's an "adventure" where there's no big bad, no mystery to solve, nothing to do – the plot goes nowhere, just a few events going on in the background (one piece ended in a graveyard and now you have undeads, one was taken by goblins whose leader is now developing psychic powers from keeping the stone in his crown, etc). Players may or may not engage, they may solve whatever they feel interested into however they want, and will eventually leave the place with no end-of-the-world plot forcing them to do anything.

I suspect my players don't remember anything about the "plot" there, but they remember the trollslayer almost killing a kid who was the only survivor of a farm overtaken by the goblins ("Something small moves between the two buildings" "I rush and attack" "… do you want to try and see what it is?" "I RUSH AND ATTACK") or the other dwarf going stealth and dropping into the unsuspicious, unguarded stable with a hole in the roof – only to be eaten by the troll chained there.

Or in another adventure (Season of the Witch), it was interesting how they completely abandoned the witch plot and got entangled with the high elf ambassador. That one was interesting and it was a case of "bounce" forced by the published material.

One of the players was a noble elven offspring sent away from his family to live among humans due to his "lecherousness" (ie he consorted with humans and was considered scandalous). So, I acquire the adventure and briefly read what it is about. The elven ambassador is a minor character, that serves as foreshadowing for the reveal that the "witch" is a dark elf and dark elves are planning an invasion. The ambassador is a dark elf in magical disguise, meant to drop a few sentences and perform some ominous actions and then play a role in the scripted climax.

Except all the details we get on her scream "his character would know about her!". They come from the same town, both are ambassadors, she claims to have arrived from the town the group was in some weeks before. My player immediately attempts to bond with her, as he's been an outsider until now and finally can talk with someone who shares the same culture and experience… except they don't, and so the plot is unveiled fairly early. Which in turn makes the clash between the sigmarite priest player and the witch hunter that arrives in town even better, because the menace is clearly over and the guy still wants a purge. He needs to see some people burn, and the priest will have none of that, so you get two religious fanatics fighting over morals to great effect.

I guess the main takeaway for me is that I don't really see this type of content working when one or more players have read or experienced it. Having 4 interchangeable villains does nothing to this end – running the adventure straight would barely qualify as play the first time through. Running it again with another villain would be pure performance.

At the same time I like using these modules as a GM because they offer a type of constraint that fully GM-generated prep or content improvised at the table don't – I really feel like I'm playing, as a GM, because the content will constantly throw things at me that I don't want or have no idea how to use and I love reacting to that.

In several roleplaying texts you will find sentences such as "the DM runs the world". Ideally a setting and with greater focus a published module should create a situation where the game/module runs the world, and the GM and players all play some characters within it, with the same level of constraint. The GM will still have some extra responsabilities, but he won't be running something he made up or can continue making up during play.

Ron, I appreciate the clean

Ron, I appreciate the clean hacking through the emotional/social issues at hand to get to the real threat to play that is going on in situations like this. Often the emotional/social issues are what creates the barriers to play, so it's helpful to see that getting hung up on that stuff here would be missing it.

When I use a module, I certainly don't think about it as something to slot in as it is — it's got to be integrated into the previous fiction and constraints established at the table, same as any prep. I agree that the idea that it is a kind of pre-packaged play experience that provides everything you need is a problematic one, and I've seen it seep into play, my own and others'–the sense that instead of bringing our real concerns for play to the table that we are playing "through" this thing to get the experience of "it". So that's a concern to be aware of when using modules, for sure. Ditto the idea of a module providing pre-set outcomes.

What do you mean by this? Certainly modules can't be considered to be fully modular, that is, usable by any group playing the game(s) they are designed for (because not every group is going to have the constraints that provide a fruitful space for the module, or the interest in what content the module brings to the table), but certainly they are usable by more than one GM as a part of prep in more than one game group in more than one instance of play. Am I missing what you see when you read "modular"?

Lorenzo, when I read this,

I get very curious. Do you really strongly suspect that published modules (as a concept, a designed thing, a way a GM preps for a particular game) are inherently bad for play? Certainly we can point to any number of shitty modules that provide expected outcomes and encourage the GM to abusive arm-twisting behavior, or to the scorching toxicity of the Dragonlance modules and what they and their ilk do for play, but to say that modules in general are probably bad for play seems way too broad to me. I want to prep, say, a dangerous magical location that for various reasons will be of interest to the players and their characters. I can prep that by creating it from some inspiration, or I can prep that by creating it from a module that inspires me. I don't see much difference between these two, other than that one takes a lot less time.

I enjoyed your write-up of the WFRP 3 module & play, and it seems like it worked well for the group because you were not interested in forcing them down any particular path, but only used the module as prep to create situations, constraints, and connections. And very good point about modules providing constraints for the GM, both in prep and directly in play.

Oh, and yeah, the whole "any of these 4 people could be the bad guy — you can play this module again and again" is total BS on the face of it.

@Hans, considering that this

@Hans, considering that this exchange is buried in Sean's comment, and also that a file is already open on my screen that is painfully turning into a reply to your previous comment, I think we need to break out into a one-on-one dialogue. It should even be a real conversation if possible, recorded and made into its own comment stream here. I'll get in touch.

Links to larger versions of the maps.

The images in the post were originally larger, so here they are at a more readable scale:

Hep-Lazar (Region) Map

Marklands of Uth (Kingdom) Map

If you don't mind dropping these links in at the end of my post, Ron, that would be great.

Both images are still full

Both images are still full-sized if you click on them, using whatever your device or browser does for that purpose.

To make big images or other bulky information more distinctively available, attach them as files. I've done that with your images now, rather than adding links.

I really prefer communications like this to go through the Contact function here or a direct message at Discord.

déjà vu

This looks and sounds like a wonderful game to me. I really enjoyed reading your descriptions and looking at your maps.

That said, I recognized the moment when your player told you that they knew the tower they were looking at. It reminded me of the moment I figured out that the "Gamma World" game I played in was set in Norrköping. I did not know if I was supposed to know this fact, should let the other players know, forget or use what I know about the place and what not. For a couple of sessions I was constantly grinning inside because I had so much fun with figuring out and recognizing things but sad at the same time because I thought I couldn't share that fun. That I wasn't meant to use my local knowledge in character was the easy thing to figure out. The rest was a little more difficult. For example, when playing online I always try (with a widely varying level of success) to concentrate on playing the game, not chatting about other things. The reason why is that time is so precious, I barely can manage to concentrate for 1.5-2 hours at a time and I think it is similar for a lot of us.

Why I didn't simply dm the gm when I figured out where our characters were is beyond me today, but sometimes I'm still stuck because I suspect unspoken rules of conduct all around me.

The situation got resolved when the ball dropped for the next person at the table. Actually it led to a lot of socializing and sharing information about the places we all live at in a really nice way.

In general as a player I don't have a problem with pretending I don't know a place I know. What will happen there will be different from any previous time anyway because a place is only a little part of the whole picture. Any person taking the time to prepare a game for others to enjoy should not feel like you let people down if you use things from your bookshelf or the internet to make the worlds our characters live in. After you described it to us we are there together to make it our own. The thing that is difficult is to figure out is whether it is more polite to tell you that I know where you send us or to keep it for myself.