Introduction in English

So Ron and I had a great conversation which he just published here about this experimental play group that I started and which has been going for quite some time now. Since we have been doing this for some time, we have a bunch of play reports, and we talked about publishing them here as well, since this is a big collection of how we play. Do look at the conversation for the context of what this is all about. Republishing a play report like this raises the question of what can be said that hasn’t already been said about it, and perhaps these posts (I intend to publish more play reports on Adept Play) will not be much more than repositories for the texts, bnut on the other hand, each report does talk about a specific theme regarding play, so if there are people here who are interested in discussing these things as I post these play reports, I’d be delighted to discuss them here.

This report is for our first session, which was all about testing the concept in itself, and not on any specific theme, which means I welcome any discussion about this thing we’re doing, about how it went, the skills required, or about GM-less freeform roleplaying. Looking at it now, it seems it was almost a year ago already! If anyone is interested in doing this, Swedish speakers are welcome to join the Discord server and plat with us, and for speakers of other languages I’d love to talk about the process or to play with you, if you are interested (I feel comfortable playing in Swedish, English and French, and probably in Portuguese, too, though I haven’t actually done it yet).

The play report below will be in Swedish, and Ron has said that he might run it through Google Translate and fix it up into Proper English. [done! – RE]

Without further ado, here is our play report for the first session:

Igår var första spelsessionen med “Hantverksgruppen” via Discord. Tanken med Hantverksgruppen är att öva på rollspelens “hantverk”, på själva färdigheterna vi har som rollspelare. Saker som beskrivningar, scensättning, rollgestaltande, dramaturgi, och så vidare. Gruppen är öppen och vem som helst är välkommen att delta. PM:a mig eller någon annan i gruppen om att få en inbjudan till HemCons Discord-server, där spelandet sker. Planen är att spela en gång varannan vecka, på lördagen klockan 19, så nästa tillfälle är lördag den 11:e.

Första sessionens syfte var inte att öva på något speciellt, utan att testa spelstilen. Denna spelstil utgår ifrån tre ingnar:

- Ingen spelledare

- Ingen mekanik

- Inga förberedelser

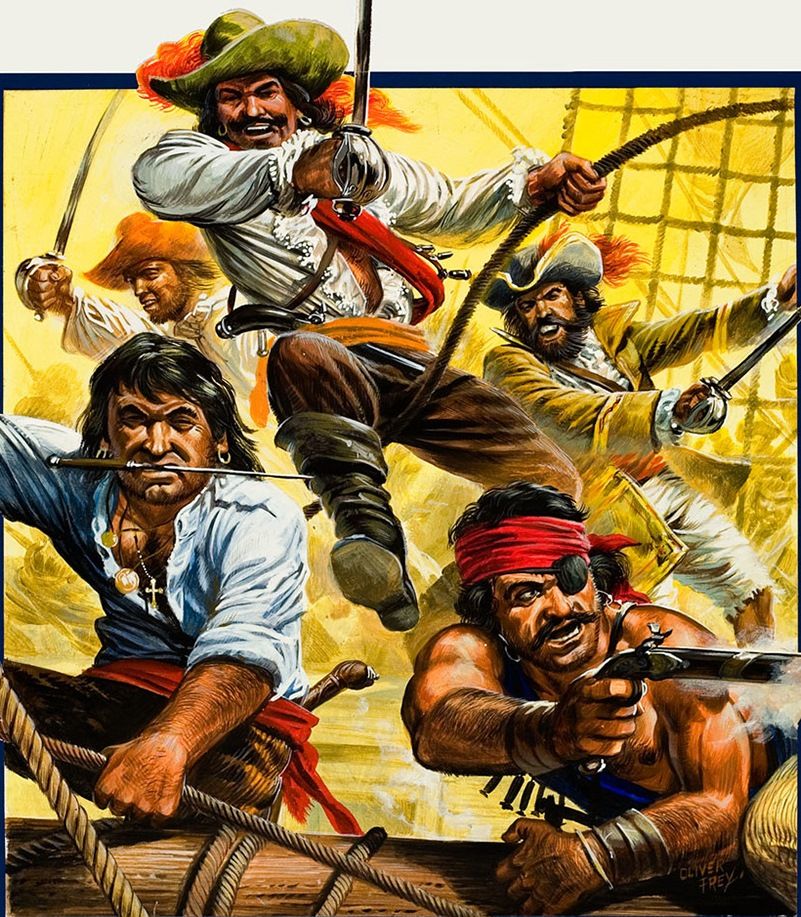

Jag, Lukas, Zonk och Kim deltog i första spelmötet. Efter lite försnack och skitsnack satte vi igång. Den enda förberedelsen vi tillät oss var en diskussion om “linjer och slöjor” samt en genre. Vi sade att vi skulle spela pirater. Det var allt. Inga rollpersoner gjordes, inga relationskartor drogs upp, inget sades om spelvärlden. Zonk satte första scenen: Fyra personer i en liten roddbåt mitt på havet. Med utgångspunkt från detta improviserade vi fram en berättelse om svek och lojalitet, om hämnd, om att sälja sin själ och att betala för sina synder. Här är baksidestexten på romanen:

LaFayette, Montague, LeRoy och Pierre är de enda överlevande piraterna från en kidnappningsoperation som gick fruktansvärt fel. Tio år senare dyker den ansvariga kvinnan, nu en fruktad piratdrottning kallad Den röda markessan, upp i piratstaden Port Royal där de fyra piraterna nu lever skilda liv. Deras öden vävs samman igen i en plan för hämnd som kommer att få konsekvenser inte bara för dem själva, utan för hela Port Royal och för deras odödliga själar …

Det var skitkul! Spelstilen fungerade jättebra och alla visade upp imponerande improvisationsfärdigheter. Vi hade en del eftersnack efter sessionen. Här är några av mina reflektioner:

- Spelstilen tillåter ordentliga, dramatiska och komplicerade historier på kort tid. Vi hade ungefär två timmar speltid, och vi avslutade inte för att vi fick slut på tid utan för att historien kändes klar. Jämför man detta med de spel vi ofta spelar i Indierummet är det riktigt bra, med tanke på att dessa kräver tid till förberedelser och regelförklaringar, som lätt kan ta över en timme. Här är man igång och spelar på en gång, och 100% av tiden går åt till spel. Man behöver inte ens sakta ned för att använda mekaniken, då det inte finns någon mekanik.

- Vi sade i försnacket att något som ofta ställer till problem för den här typen av improvisation är en ovilja att trampa på andras tår. Att man inte vill ta beslut som rör andras rollpersoner. Vi var duktiga på att undvika detta och etablerade saker om varandras rollpersoner som inkorporerades på ett snyggt sätt.

- Det gick förvånansvärt snabbt att komma igång och få till drama och relationer. Jag kände aldrig att jag saknade ett förberett relationsschema att falla tillbaka på.

- Den här spelstilen är säkert möjlig tack vare att tre av oss redan spelat många drama/hippe/improspel och har vant oss vid många av principerna. Det känns troligt att fyra nybörjare som skulle försöka sig på samma sak hade haft mycket mer problem. Men detta är också poängen med Hantverksgruppen: att fokusera på att bygga skicklighet som rollspelare och improviserande historieberättare. Det är inte ett problem att det är svårt: Det är en feature!

Så, Hantverksgruppen kommer att fortsätta. Från och med nästa gång kommer vi att ha ett ämne varje gång som vi vill öva på. Vi har en lista på Discord över ämnen. Reglerna är att vem som helst kan lägga till ett ämne på listan, vi betar av dem i kronologisk ordning, men vi jobbar inte med ett ämne om inte den som föreslog det deltar den kvällen. Ämnet nästa gång kommer att vara “Beskrivningar”, om inte Zonk får förhinder, i vilket fall det kommer att vara “Scensättning”.

8 responses to “Hantverksklubben first play report”

Interrogation

Hi Simon! What strikes me about this first Hantwerks session is how minimal the preparation was, compared to your description of the sessions that followed, or at least a lot of them, as they evolved.

In this case, you laid out the principles, said "Pirates," and play proceeded – I don't know how much elapsed time (not counting the gossip + bullshit), but apparently, not much.

Now … at the risk of spoiling the romance about "no mechanics! no GM!", when I think about my play experiences of this sort, that they included a lot of "mechanics" and things a GM does. The former are non-representional, e.g., how much numerical damage is done by this axe as determined by rolling dice, but they are nevertheless present as procedure which makes the fiction "go." The latter, perhaps less compromised by terminology, are conducted opportunistically per person rather than by a single person.

Since your first session included people who'd played together a lot before this, I'd like to know more about what you all did during play, when fictional event X happened and then Y happened because of it, and then Z was the result.

I'm definitely not refuting or devaluing what you're describing, either as its own single experience or as part of the Hantwerks activity. I hope what I'm saying can be understood as the opposite: that we do have powerful and fun procedures at our fingertips, and we do organize the principles and procedures of play, without relying on the historical "shapes" these things happen to have taken.

The reason I'm harping on this so hard is that I saw a similar and very sincere endeavor go horribly awry with a famous experimental play group in the mid-1990s, most of which was published by Hogshead Publishing. In that case, however fun or positive their actual play may have been, the resulting procedures as published were exercises in competitive control and griefing (e.g., The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Pantheon). One of the exceptions, Puppetland, solves the problem but goes all the way to the endpoint of pure single-person dictatorial control, and the one attempt to reconcile non-consensual and proactive play with rising action, Once Upon a Time, ran straight into purpose-confusion that cannot be resolved.

Understanding the rules your first session used – arrived at, discovered, invented, however we want to say it – is critical so that people learning from Hantverks can appreciate what you're achieving.

Ok, so I’m definitely not

Ok, so I'm definitely not saying we didn't have procedures; I'm using the word "mechanics" here do differentiate a KIND of rules, as opposed to other kinds of rules. By your definition, I'm sure we do have mechanics. I just find that in my vocabulary, this is a good term to describe the "dice, attributes and conflict resolution" kind of rules.

I talk a bit about this in my book. I think the key to making this work is "play to lose". I'm not sure of the origin of this phrase, or if it's common in the anglosphere, but it's quite common in my corner of the Swedish RPG world. Basically, nobody is advocating for their character. Nobody is trying to get the best result for their character. Rather, we're all trying to get a good story going, and that often includes sabotaging for our characters. There is a bit of nuance here, which might be hard to get across, but I'll make an attempt: We're all sympathetic to our characters, we all care about what happens to them, and we never abandon them. We let them make their choices, even knowing they are bad ones, we walk beside them and when they suffer the consequences of their actions, we suffer with them. However, we don't make decisions based on what's in the character's interests.

I have an example in my book. There's a door in front of your character, and you say "I open the door and go inside". No roll necessary, right? In any normal circumstances, no GM would tell you to roll DEX to see if you stumble on the threshold. So, does this mean that characters in RPGs never stumble on thresholds? No! You may very well describe your character stumbling, getting really embarrased by her clumsiness. Maybe there's a hot guy and you're devastated that you stumbled. This can absolutely happen in a game, right? And that's interesting! If that happens, you, the player, with no constraint from the game or the other players, voluntarily sabotaged for your character. She didn't want to stumble, but you MADE her. Just like in your example with the player who hobbled their character after taking a big hit in a combat. This attitude is what I call "play to lose". You're not actually trying to lose, but you're explicitly NOT trying to win.

The attitude I generally have, and that most of my games aim to foster, is one of play to lose. This doesn't mean there's no challenge. On the contrary! There's a challenge all the time. The challenge is to tell a dramatic story, and there's absolutely player skill involved here. But instead of deciding wether to your Magic Missile or to save it to the next encounter, you are tactically choosing wether or not you want to win this fight. What would make for a more interesting story? That's absolutely a question of skill.

This view refocuses play in a way that puts all players on the same side. We're ALL trying to make a compelling story, so if it's more interesting for me to lose, we BOTH want me to lose. So no mechanics of arbitration are necessary. We just play it out.

So then what if we have different opinions on what would make a better story? Well, in that case, probably both outcomes make for a compelling story, since there is one player on each side. So any outcome would be fine. No problem! If there really is a heated disagreement here (in 19 sessions there never has been), we would talk about it. I don't think using dice to solve such differences would be productive, just like using dice to decide whether Frank can play a zombie in our Western game would be productive.

So an example, from this very session. Kim's character has swallowed the black pearl and he is driven to madness by it, as it gives him great powers. But at the same time it is consuming him. He and the Red Marquesse are fighting on a burning ship (of course it's burning!). Thus, Kim and I think Lukas are narrating their combat. Swords flashing, yells and insults. Then I narrate how my character is climbing on to the ship. We talk, but then the Red Marquesse attacks again, and as Kim attacks her, I stab him in the back. (Details may be a bit off by memory, since this was a year ago, but the point stands.)

So how did we do this? Well, I just described how I killed Kim's character. We didn't even have a roster of characters here, this was his only character. I go "Ok if I kill you?" and he goes "Hell yeah!". That's all. We've had several combats like this during our games, and since we're all playing to lose, there's just no disagreement. The procedure is generally "Whoever says they win, wins". Or sometimes someone will say they lose. Occationally I've thought it would have been cooler if the other outcome had happened, but that's fine, and it would have happened with a dice roll, too.

Does that answer the question? That's pretty much the procedure for handling conflicts. Someone says who wins and then we keep playing. I think crucial for this is that the game is fragile. It's easy to ruin this game. I can say "I kill everyone and become king of the world" and that's it. Because there's no challenge, there's no temptation to do that. What would you win by it? Give people a game that's hard to break and that's a challenge. Give them a fragile game and there's no challenge, so nobody is really tempted to break it. What would be the point?

I find this discussion

I find this discussion fascinating, because one of my tentative conclusions about roleplaying has been that trying to play with an eye towards creating a good story doesn't work, or at least it gets in the way. To be more specific, if while I'm GMing I start thinking about story structure ("this part needs more rising action, so I'd better throw in a bad guy attack now" or "I need to address this part of that character's inner wound somehow") then I get stressed and stop having fun, and I tend to start doing intuitive continuity, which interferes with the autonomy of my players.

Now Simon, based on your description everyone's having fun, so you may have proved me wrong on this point. I understand there's no explicit GM in your games, which means the standard GM duties/authorities are shared by all. I'm very curious to know more about how the goal of creating a good story guides your play. Does everyone agree on what a good story is? Do you have some implied rules or procedures that guide your play towards that?

I’m not sure if I have

I'm not sure if I have grasped how comment hierarchy works on this site. Let's see if this comment ends up where I hope.

So the autonomy part is obviously less of a problem when doing GM-less play. In fact, the way we're doing it now (but not in that Pirate session) where we have no character ownership, we sometimes do completely railroaded scenes, or even monologue scenes where only one person gets to talk and it's fine, because no player can control the narrative, even if you take full control of that one scene.

When it comes to focusing on story structure, I don't think we think about it very explicitly. I can't speak for the others, but I rely more on "story feel" than on any Hero's Journey or Egrian Premise. An understanding of these things is quite helpful, but mostly to develop a feel for good stories. In the moment, I rarely think about structure, though I do think a bit about things like addressing something that was established earlier, making a nice reference, and so on. If I or someone else manages to get some of these things, it's a real "Yes!" moment. Like, in the last session we played, Björn introduced in the very first scene that the main character picked up a broken watch and stared at it. This is something we call "The Jeopardy Trick", i.e. starting with the answer and coming up with the question later. Björn loves to do these things and he's quite good at it. So he introduces this pocket watch, but he has no idea what it means. Later in the game, he sets a flashback scene. In this scene, I start describing a bunch of mexican soldiers (it's a western game) who are firing at our hero from an ambush. Björn then describes how he falls from a bullet in the chest. Then later, of course, he picks up the broken pocketwatch again and looks at the back of it, which has a bullet embedded in it.

So that part is all improvised, and the skill of making a connection like this on the fly is part of the fun, right? So rather than stressing about it, it becomes part of what makes play interesting, and getting these things to click is a real feeling of skill and accomplishment as a player, sort of like executing a clever tactic in a combat game.

No, we have no implied rules or procedures that guide us towards that, and I really don't think it's necessary. Something that has continually astounded me when playing these "samberättande" games (a Swedish RPG term litterally meaning "together-telling", where players have a lot of authority to shape the story beyond just the actions of their characters, for example by setting scenes) is how a story structure evolves quite naturally when players are left with the freedom to shape the fiction. I have seen again and again how halfway through the game, there are a bunch of loose threads and I'm really not sure how all of this is going to come together, but then as if by magic, we tie it up and get a really satisfying finish to the game, without any endgame mechanics or other rules to guide it. In fact, I think the absence of such rules is a plus, since they will often fail to take into account all the subtleties of the fiction. The only implied procedures are that we keep an eye on the fiction as well as the clock, so when doing a oneshot we know that we need to stop introducing new stuff at a certain point. The fact that we play oneshots may be an advantage, actually.

I think the underlying structure that we're all working with is that of uncertainty. In the beginning, we introduce uncertainty. We raise questions, trigger our curiosity. In the middle, we answer some questions and pose new ones. Then at the end, we stop raising questions and focus on answering the ones that are unresolved. I have an explicit mechanic for this in my game Nerver av stål (available in English translation for free here, if you're interested), where you write down all the unresolved questions as you play the game. It's a really good mechanic for improvising a mystery and then resolving it, but I think the basic logic behind it is fundamental to how stories work and it's the thing we do naturally when playing. I'm not sure how much of it is "natural story instinct" and how much is skill acquired over years of story-focused gaming, though. A bit of both, surely.

Now, some of the stories we've played in Hantverksklubben have been more "traditionally" structured than others. Part of the stuff is experimentation, and some of the stories have been quite experimental, but then, some really good non-RPG stories are, too. Sometimes the thing that engages us is more the form than the structure (like when we're focusing on the language we are using), which is fun, too. But there's always an element of trying to get the best experience out of the game, and relying on our skills to do that, whatever we are focusing on for this session.

Then later, of course, he

It was even better, actually, now that I think about it. Our hero was on the run from his past sins, and the story was about how his past came after him and in the end it got him killed, and of course Björn had him note, as he picked up the broken watch, how it was a reminder that he was "living on borrowed time". That solid reference was an instance of storytelling skill that really made us go "YASS! Nice one!".

I finally chose a small part to think about

I want to investigate or reflect at second hand about characters and players.

I struggled a little bit with this. I think it means that the group of you did play in ways that concerned one another's characters, so that each person did not play in a bubble of one character and their little personal situation, per player. Or to state it without all the negatives, each person played attentively toward and into the situations of other people's characters. Do I have that right?

It also raises the question of whether character ownership … more accurately, a specific kind of authority per character per player (not "total authority" at all) … evolved at the table.

I think it means that the

In this first session, we actually had fixed characters. We didn't develop the "no character monogamy" style until a few sessions in. What the part you quoted was about was the way that without any resolution mechanic or any apportioned authority, we run the risk of hesitating to invent things that affect others' characters. One obvious way is conflict. If we have a combat scene, the risk is that nobody will want to decide which side wins, because they want to avoid stepping on the toes of the other. "Maybe X really wants to win (or lose!) this fight, so I'll let them decide". It could also appear in other situations where you want to improvise something that concerns another player's character, like a piece of backstory "I'll never forgive you for betraying me and leaving me for dead in Bermuda!"

So that's the part we were worried about. In practice, we handled it quite well, and it has become even easier to handle when playing without character ownership, since it's easier to make up stuff about a character that doesn't "belong" to another player. Again, the rule for contributing to the fiction is basically "If you say it it's true, unless someone objects" (and as of yet I can't remember that we've had any objections).

As for developing ownership/authority over time, that has happened in some games and not in others. Like I said, in this specific session, we had fixed characters from the start. In the sword and planet game I mentioned in the interview (theme was "scene setting"), we developed a "more or less" character ownership during play. I think some characters became more of "player characters" and others didn't. In a different game, of wagnerian mythic age (theme was "aggressive scene framing"), a sort of hybrid situation arose, where we had some four or five main characters, and a sort of overlapping ownership, where for example I often played two of the characters, but never the others, but I wasn't the only player who played them.

I'd say there are a few things that influence how this turns out. If we have only one or a couple of protagonists in the story, we will all play them, since any kind of character ownership would leave some players completely without characters to play. And if we give the same role to the same player twice ("You played her so well, you get to do that again"), then you create this kind of association that tends to stick. I'd say an important part is exatly that – if you play a character in a very specific way, with a strong personality, speech pattern or other characteristic, you sort of set your mark on that character, and it becomes more difficult for others to play them. This became more clear in our "characterization" session, where we explicitly practiced conveying a character's quirks and personality through playing. We explicitly wanted to share these characters, and we did, but we did tend to give them most often to whomever played them first.

I find both styles interesting and fun. This is one thing that would be interesting to see in longer play of some 5-10 sessions.

Excellent clarification,

Excellent clarification, thanks!