Metatopia 2020 was an online event held on Nov. 5-8. This is an annual conference that focuses on small press and independent game designers. Panels covered a wide variety of topics, and the quality, as is to be expected, was varied.

Metatopia 2020 was an online event held on Nov. 5-8. This is an annual conference that focuses on small press and independent game designers. Panels covered a wide variety of topics, and the quality, as is to be expected, was varied.

Two panels in my mind stood out. They touched on issues of interest to people here at Adept Play, though they sometimes came at those topics from different angles. Here, I’ve tried to boil down those panels into their salient points. Both of these topics would be worthy of further discussion, either in the commentary thread here, on Discord, or in Monday Labs. These notes are mostly in the order of the ideas as they were expressed and they reflect the comments of the panelists involved.

Panel: Games, Gamefeel, Vocabulary, and Umami

James Wallis was the moderator and here is his elevator pitch for the session:

In the early 20th century, a Japanese chef introduced umami as a term to describe the 5th basic taste, and this enriched the way that people talked about food and drew attention to another dimension of taste. The language we have to describe games is in need of a similar linguistic enrichment: we need to focus on the experiences and the emotional impact of games, and we encounter situations where we seem at a loss for words and would benefit from some new vocabulary. Often we are left borrowing words from other realms, but we would be better served with a more robust arsenal of specifically game-oriented words.

Kieron Gillen referenced a manifesto he wrote in 2004 advocating for a “New Games Journalism.” Note that Gillen was referring to video games in that manifesto, and he set as the goal of this new approach the description of “What it felt like to be there when it happened”. He goes on to write “In videogames there is no ‘there.’ You’re either sitting in front of your PC or slumped in your front-room, controller in your hand. It’s all happening inside your head, induced by how the sound and light you’re bombarded with alters depending upon your whim and inclination. You’re experiencing something that simply doesn’t exist. This is the games-form’s own peculiar magic, and what we have to explain.”

Cat Tobin brought in her experience with the Nordic larp scene as well as her work with Pelgrane Press. The larp scene has thought about the emotional dimension of gaming and has reflected extensively on experience such as “bleed” which describes the way in which a character’s experiences in the game can transfer or bleed into the player’s own emotions. She argued that we need to have a more refined way of talking about the lived experience of inhabiting experiences because so much of that experience is happening in your head and can’t be adequately recorded–it can only be subjectively described, and we lack the necessary vocabulary fully to capture this phenomenon.

Jacob Jaskov is a philosopher, political scientist, and futurist. He has worked on a long term project in the Danish library system aimed to help people be more engaged in reading. That project aimed at enhancing the language to talk about books, and it was built on a three-year study of how people experience books, and how they intuitively locate new books to read. All fiction in Denmark is now being categorized using this new system. Notably, the approach is moving away from the sometimes confining limitations of traditional genres (plus it helps readers discover new books and be more engaged in them). He is proposing that we might start to do the same type of thing with games. Wallis pointed out that we usually talk about games in terms of mechanics or subject matter, and this often leads us to games that prove to be disappointing–because what we need are categories and definitions that would more closely hit on the feelings that we are looking for when we play.

Wallis gave a nod to the rich work that has been done on games mechanics and systems, but he argues that we should consider more fully how such things make players feel at the table. Kieron chimed in and said that we should talk about games in a more anecdotal way and think about such discussions as a kind of “travel journalism to imaginary places.” Such an approach, he says, is more natural and leaves more room for engaged writing. He also endorses borrowing from other fields of criticism when it is effective and interesting to do so. Kieron made a point late in the panel that we need to also focus on a vocabulary to more fully describe gamers/players in terms of the types of experiences they are seeking.

Panel: The Devil in the Details: Designing Microsettings in Tabletop RPGs

Panel moderator Richard Ruane opened by asking “What is a microsetting?” According to the panelist Brian Yaksha, microsettings fill in all those details you don’t get in a larger product; it is modular content tailored to a tone that has enough utility that you can strip away the elements that you don’t want to use. It is a toolkit designed for a specificity of purpose that celebrates the material its talking about than more generic products or larger settings will allow.

A microsetting is filled with an intrinsically subjective set of details. It is not trying to be encyclopedic, but it is trying to give a buffet of details that can be usable for gameplay and which are flexible, allowing the play group to pick and choose. They create a “gameable lore” that is both useful and personal.

Microsettings also create experiences that seem real and concrete. A number of panelists also felt that microsettings are able to draw upon the personal experience of the writer more effectively. They designers felt like larger epic settings don’t sufficiently capture lived experience in a way that is compelling and vibrant.

The advantage of microsettings (again according to Yaksha): Microsettings have a clarity of purpose; they celebrate the material because they drill more fully into the emotional core; and they capture an organic experience that seems to have integrity.

Microsettings often go after the important details that the larger setting objectifies, glosses over, or devalues. Microsettigs can spark alternative narratives that exist in reaction to the dominant narrative of the larger setting.

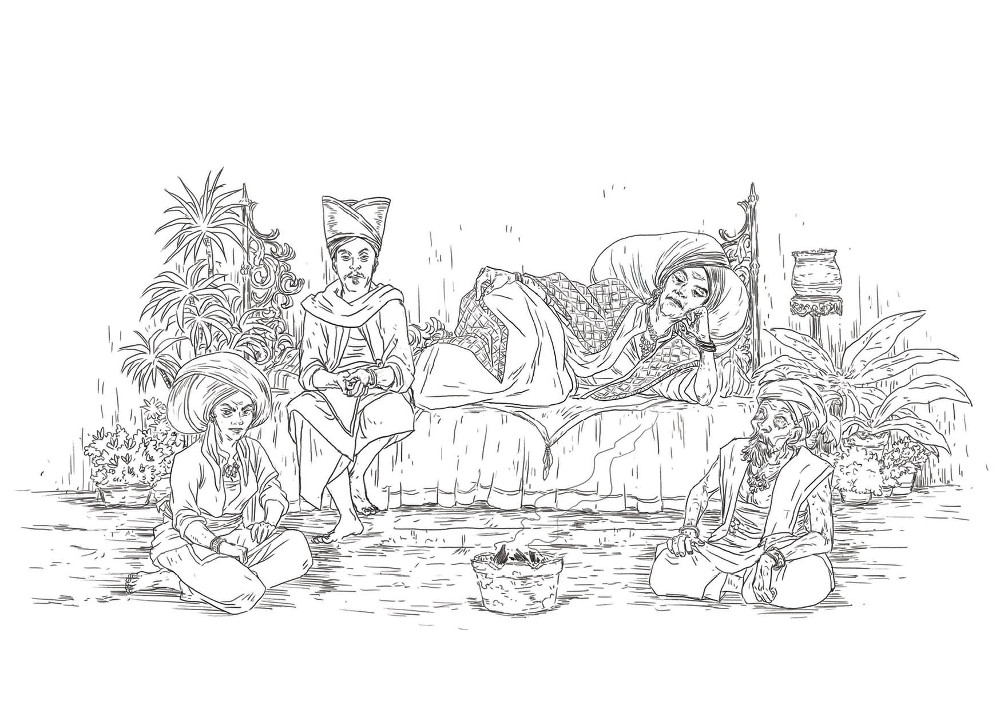

Zedek Siew also talked about the way that it is very possible to create microsettings in a world for which there is no larger campaign setting. His project of The Thousand Thousand Islands is conceived of as being only a series of small zines without any epic setting background. It is microsetting all the way down.

Writers from marginalized groups often find microsettings more appealing to work within: Diversity and the experience of marginalization can often come out in a microsetting in a more powerful way. Macrosettings can have a way of diminishing or eliding the voices of those living on the margins. The microsetting requires us to think more about who and where the characters are in a focused and intense way.