Nathaniel Duhring arrives in New Orleans, nineteen, broken, -hearted and otherwise. He has just fled the travelling circus that employed him as a freak act—the Puzzle-Pieced Paddy, surgically dismembered and reassembled time and again for the awed entertainment of cycling crowds. Nathaniel’s feelings toward the surgeon are hundredfold and conflicting—here is his mentor & tormentor, his ticket out of the small, bounded life of an immigrant’s son, out into worldly terror. Nathaniel’s agony feeds his four-year-old son, Nat Jr., but the circus is a novel prison. As the caravan shoved off westward from this sodden city, Nathaniel and the boy slinked away into the foreign bustle. Here, he is saved—not for the first time—by his faith.

Though Catholic by birth and upbringing, Nathaniel’s devout potential is gleaned by local Protestant minister, Reverend Cornelius Loftus. Loftus grants Nathaniel refuge in the church’s basement, while young Nat is gifted the security of upstanding adoptive parents, Timothy and Abigail Wyatt. In Abigail, Nathaniel glimpses echoes of his lost beloved, Jr.’s mother, dead of yellow fever and buried in the Duhrings’ distant hometown.

Inflated by Rev. Loftus’s outpouring of support, Nathaniel obsesses over the peculiar notion of his personal worthiness. At the docks, Nathaniel finds relief in menial grunt work. Despite the arduous labor and sweltering humidity, he dresses to conceal his ubiquitous scarring. For this, Nathaniel is made the subject of his coworkers’ ribbing. At shift’s end, he drinks—too much—alongside, but not with them.

What will Nathaniel make of this new life, he wonders, and sets out to pinpoint the crux of his importance, his selfless purpose to the not-yet-saved.

Introduction

I recently wrapped up a long-running duet of Nathan D. Paoletta's Imp of the Perverse. Imp describes itself as “a game of Jacksonian horror” that draws on the work of Edgar Allen Poe.

Participants play Protagonists, individuals made exceptional by possessing a Greatest Strength, a passion or heroic quality that ties them to others, and a Perversity, a uniquely twisted quality that pulls them toward the darkness.

Each Protagonist is afflicted with an Imp, a supernatural creature drawn to our side of the Veil by their perversity.

This game was one of the best I've had the good fortune of participating in. I wanted this post to be comprehensive. To sum up the fictional events and thematic developments of 7 months of play into a dense, yet graceful longform essay.

To bookend this project, I asked my duet buddy to write one description of his Protagonist at the beginning of play when his Humanity was at 5 and another of him at the end when, after struggle upon struggle with his Imp, he departed play at Humanity 1, having become one of the monsters he fought.

However, the more I wrote, the more I felt like I was analyzing abstract mechanics, not getting at the heart of what made this game so impactful.

So instead of trying to write about the game with any attempt at exhaustiveness, I decided to zero in on two emergent behaviors that we discovered, like melodic hooks in improvisation, that I want to carry into future play.

#1: Shared Aesthetic / Language

Imp of the Perverse has a very distinctive vocabulary. Player characters don't advance or level up, they undergo 'Ontogenesis.' They don't have pools of mental resource points, they draw on 'Ratiocination.'

Somewhere in our first three sessions, we began to lean into this. My buddy's Imp's first appearances were announced by 'Angelic Tinnitus,' rather than just plain ringing in his ears. When he gained his first Impish Edge, it wasn't super-senses—he gained Adamantine Hyperaesthesia. A few Chapters later, he wasn't shooting lightning-bolts from his fingertips, he was unleashing a Galvanic Charge.

While these might seem like small details, they went a long way toward making New Orleans feel like our Imp-haunted harbor. And it had tangible effects on how these Impish powers actually functioned. Sure, 'Lightning bolts' would have served to zap enemies just as effectively as a Galvanic Charge. But with its suggestions of early Galvanism and Dr. Frankenstein, my partner discovered all kinds of interesting uses for this Edge that probably wouldn't have emerged under a different name.

This is a dynamic I've also observed in naming Powers in Champions Now. Even if my 'Freezing Ray' and your 'Skeletal Grasp of the Grave' are numerically identical Entangles, given a few uses they are going to be radically different abilities.

Periodically revisiting names was another powerful way for us to make and mark changes in the fiction. Imp enforces this by having players rewrite their Protagonist's Greatest Strength every time it hits '0.' Each time this occurred was an opportunity to see how this core aspect of our Protagonist had changed.

One thing I'm not sure of is how much a name can accomplish on its own. In Champions Now, characters have a constant drip of points that allows players to sculpt the Powers into new, surprising shapes. While Edges in Imp don't quite have this level of differentiation, they do require an Exertion Roll, and each such roll means a player is betting a piece of their Protagonist's soul. There is no ordinary or safe use of an Edge.

I think Blades in the Dark is a game that relies almost exclusively on naming to differentiate its skills. Every Ability can be used, albeit with shifting Position and Effects, in pretty much every situation. In my experience, this led, over time, to Abilities becoming more and more similar.

My talky guy can smarm his way past the guards or your punchy gal can club her way through them, but these don't feel like significantly different options. BitD's Abilities end up feeling more decorative than aesthetic.

I'm currently playing Solar Blades & Cosmic Spells, an OSR game that provides very little differentiation between items, abilities, and characters compared with Champions Now. However, the game does intentionally provide lots of flexibility when naming and inventing items. A player's 'whalebone spear' might be numerically similar to a robot warlord's 'plasma cutlass,' but time will tell if they end up feeling like substantially different tools.

SB&CS also grants PCs and significant NPCs a "Concept," a 1-sentence descriptor that specifies each character's 'thing' (e.g., 'aging rogue from a cold planet' or 'wide-eyed tech wiz determined to see the Universe'). This concept is invoked to grant a character Advantage or Disadvantage.

While not explicitly in the rules, I intend to also have everyone revisit their characters' Concepts every time they level up (NPCs included). I think this may create a sense of developing, deepening characterization, even without a ton of mechanical switches and dials to play with.

#2: Playing Fast, Playing Loose

To use the terms of S/lay w/Me (a game we played occasionally between sessions of Imp) our Chapters started 'tight.'

I played NPCs and the world as accurately as my research would allow. My partner focused on Nathaniel Duhring's interiority and the subtle social dynamics he had to navigate as a working-class Irish person man through upper-class Southern society. We rarely narrated actions or reactions on the part of each other's characters, and when we did, we asked permission before doing so.

Playing a historical game is like playing in the most detailed setting imaginable. It was important that we got the small things right, both to evoke the period and also to honor the forensic investigation that made up the midgame of each Chapter.

However, Imp accelerates rapidly. The triggers for each Chapter's "Anxiety" score are structured so that they get tripped in quick succession. As Anxiety rises, clues become harder and harder to uncover and Protagonists get closer and closer to their confrontation with the Monster. This generally resulted in us playing 'looser' in the endgame.

One of my 'Gos' in a climactic conflict might include the Monster's action, its effect on Nathaniel, and some description of Nathaniel's reaction. My partner's Gos loosened up just as much. This created a much more frenetic pace of play.

We also had an interesting outlet in the form of Nathaniel's Imp. In our duet, the Imp became a shared character. Sometimes, my partner would bring the Imp into scenes in surprising ways. Sometimes, I would push its dark presence into frame, keeping Nathaniel from getting too comfortable.

Effectively moving between 'tight' and 'loose' play requires careful attention to your fellow player: When does narrating their character's actions and reactions deepen their enjoyment, creating the sense that someone else 'gets it,' it being what they want out of the character (like a conversation between soloing instruments in jazz)? When does it feel like overstepping, taking away your fellow player's agency?

Our next duet is going to be Runequest: Roleplaying in Glorantha. With relatives, followers, and spirits everywhere around us, I think we'll have ample opportunity to explore the potential of shared characters.

I'd also like to get better at moving between tight and loose play in larger groups. It's much harder to do well with three or four other 'instruments' to listen to. I think shared characters may be an effective place to develop this back-and-forth musical 'texture' in a group context.

Conclusion

I'm still disappointed by how ineffective this report is at capturing what made these seven months of play so rewarding. I look back on what I've written and just see scraps, not the living, breathing imaginings my partner and I stretched between us like a tapestry.

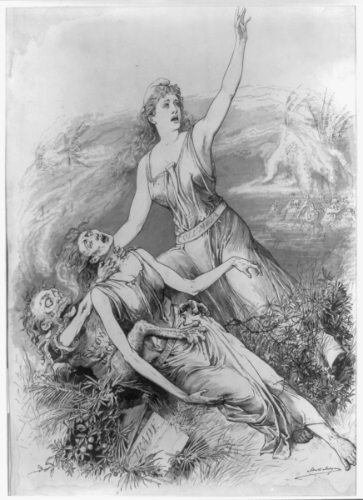

But I suppose writing about your favorite jazz album will never approach actually listening to it. My partner's verbal portraits of where Nathaniel began and ended make far better listening than my analysis. I'll end with them:

We can all be together—all of us: the living, the dead, Catholic, Protestant, servant, master. We can be one family, if only Nathaniel Duhring can tune his suffering finely enough.

This is Nathaniel’s core, monstrous belief. He has succumbed entirely to his imp’s perversity—sinking so low as to murder young Nat Jr.’s adoptive father, Timothy Wyatt—to preserve the possibility of familial communion, he tells himself. There is no sin Nathaniel cannot justify under his tenets of autocrucifism. He now inhabits the abandoned home of one of the bayou’s vanquished monsters. He has reinvented the machine which in the monster’s hands was evil, but in Nathaniel’s can be just—if only, if only… He and he alone can put this mechanism to work for good.

Into the the machine Nathaniel has wired another fallen monster, another false prophet, whose body will serve as a spiritual conduit and beacon, the central node of a universal love of Nathaniel’s making, a love from within and without, a love that will reach every corner of every soul on this plane and beyond the veil. Everyone. Yes, he and Abigail and the boy will be inextricably linked. At long last, perfect harmony is within reach. This must be the heaven preached from the good book. So why is it only me and—only me?

3 responses to “Leaving Imp-Haunted New Orleans”

I use my X to do this

Thanks Noah!

Your point about discussion is critical. The experience we're talking about is play itself – not a transcript, not an adaptation, not an essay (however graceful), not even a recording or video, because this is not about a third-party entertainment. My hope for this site is that we can appreciate and mutually celebrate our play-experiences … but we cannot provide them for one another via reports and recordings. To take your analogy further, even listening to the album is not the same as playing the music, i.e., being the musician.

Fortunately, talking about play (or whatever) as ‘musicans’ is a wonderful activity. You've raised a couple of points with hidden roots in many role-playing designs. The main one for me concerns this principle: use [this] to accomplish certain actions, but you can call it whatever you want.

It’s gone sour in several ways over the years. Bad version #1 says, well, the name you give it is a skin which doesn’t mean anything, the mechanic is always the same, so the name is customizable so you can be arty and “narrate cool” as you please. Bad version #2 confounds the openness of description with width of application, so “call it what you like” somehow also means “it can be applied in any situation.” The mid-90s brought us a tangle of nonsense which included “dice and numbers means it’s locked down, less dice and numbers means it’s loosey-goosey.”

As I recall from the late1970s through the late 1980s, this was far less of a problem or issue than it became – in fact, the whole range of what seemed to become standard in the 1990s (legalistic quantified can/can’t, vs. say-anything whatever) was considered, way back then, to be the range of bad play.

Well, this has veered into aging-man grumbling. Back to the point: let’s not be distracted by the customization of the ability’s name. The real topic is, how does the verbal name or label for any game mechanic play into how it is used? I suggest that it doesn’t matter whether this name was customized by the player or provided by the rules. If you are afforded a Strength roll mechanic right there in the rules, and “Strength” is a printed-out word on your printed-out character sheet … how do you know when it is OK to roll it to deal with some problem?

“The princess back-talks you. What do you do?” “I try to convince her that we really need those soldiers to help us. I roll Strength!” (pause) “Do you mean, uh, that you hit the princess?” “No! What do you take me for? I use my Strength to convince her.” “How?” “Well, I flex for her! I roll Strength.”

I am pretty sure most people here agree that at their table, this player would simply not be permitted to roll Strength to convince the princess (for this example, we will presume that she is not a bubble-head who is specially impressed by flexing). I specifically include the point that the player has included a Strength-y description of some action, and presumably is thinking in terms of those games in which “you can use anything to do anything as long as you describe something.”

So, my question is for anyone who agrees with me in that as a fellow player, I would indeed look at the player and say, “Ballocks.” The question is why? Why can’t they use the Strength roll? Yes, I know “it’s not justified.” Why isn’t it justified?

Once you find a good, non-circular way to explain this, and that also includes not going into the well-greased slide-y pit of what “would” or what “is,” then you’ll find that the precise, same answer applies to using abilities that you did provide your own names and concepts for.

A lot of my designs address this same topic, but as it happens, Bezurkur and I have just managed a a pretty good discussion of special effects in Champions Now at Discord. I’ll get his permission to transcribe it to include here.

Two small reflections on the

Two small reflections on the subject.

When do I get to use Strength? My personal observation is that game text or at the very least the implied process for each game matters a lot here, so for a second I would put aside all those games that eskew the concept of "this score represent this fictional aspect of your character" in favour of all those mechanics that represent someone's capability to impact on the story rather than the pascals of sheer strength he can apply to a surface or how well trained they are to interact with a specific social class modified by how good they look to a sexually compatible partner and what not.

So if I'm playing The Pool and I'm getting my 2 bonus dice from "being driven by love +2" I may be getting them for my rousing speech to the townsfolk to come to my aid in slaying the Beast and rescuing Belle from the castle or I may be getting it for wrestling a pirate while my loved one is drowning. If I'm invoking a Relationship in Trollbabe for a reroll, what it will mean in the fiction should be immediately apparent (and I would suggest that even the "problematic" example on page 55 is on an wholly different level of complexity and usability than the "flexing for the princess" example).

So if I'm getting this right, the issue at hand is specific to the type of game that tells us in very precise way "this attribute/skill represents this fictional event".

I want to try and approach the issue from the opposite angle – as a way for myself to try and get to those answers. I'm thinking out loud here, rather than proposing some answer.

Let's say that I'm in front of a closed door. Let's say that I possess a skill (called Larceny, Lockpicking, Force Doors, Open Stuff, it doesn't matter – in fact, we don't even need the skill to be there but let's have it act as a beacon to specify that we're doing this thing) and I want to use it. Maybe I'm in the type of game that strictly tells me which ability I put with that skill (think D&D3E), but let's say that I'm not (or that if I am, I force the issue by saying "I want to do it like this").

I can go through my tools and roll with my Dexterity, obviously. This is the theorycal default scenario.

But say that I want to use my brawn, and add Strength. I'm not really picklocking anything, just using my strength on the weak points.

Let's take one step back and say that I know how doors are built. I'm not a thief, I'm an engineer or crafter. The Dexterity guy is using muscle memory and training – I want to use Int, because I'm not going through the moves, I know what I'm doing and how. Maybe I want to roll with Engineering, at this point. It could make sense.

Further step back: I want to use my knowledge of Alchemy to work that lock. I'm pouring acid in it. Do I roll Alchemy, or Lockpicking + Intelligence, or Lockpicking with a synergy bonus?

It's quite the rabbit hole.

What's our interest here? Are we rewarding playing ingenuity? At which point it stops being "creativity" and we enter the deck of the infamous Kobayashi Maru and we just wiggle around until we manage to bring in our good skills or attributes?

Are we preserving game-balance? Will the fact that the Fighter gets to roll some skills the Rogue is supposed to be really good at using Strength instead of Dexterity going to be an unfair advantage?

Ok, my little trip of self-reflection didn't produce a useful answer, but I'll be curious to hear what other people think about these points.

Regarding the issue of naming conventions and how "giving your own name to things" can work, I want to produce a personal favourite of mine (once again) as a not-so-volountary example.

D&D4 introduces a gigantic number of personal abilities ("powers") that, of course, have individual names.

Now, some of this stuff is familiar or rather intuitive, or has very informative description text, but some other things are just… up for grabs. Yes, Bless is clear, Turn Undead is clear, but what about a Distracting Flare, as a Divine stealth-assassin-duelist-wannabe jedi knight class? Deflecting Thunder? Dawn Fire Sigil? Blade Step?

You get a line or so of descriptive text, once again, but at least for us, you immediately raced to the text and effects to see what this thing actually does. And here I hold the opinion that in its own family of games D&D4 achieved – I can't say if intentionally or not – the almost unique effect of forcing you to extract the actual, visual effect of what that power actually was in the sense that matters (ie "what's going on, in the narration?") from the mechanic. And this process played out as a translation, as the authors' intention was either not always clear or much more focused on the mechanical effects on the very complex tactical implementations.

You made the powers yours. There was no other way because there were hundreds of them, and they were clearly created to perform certain functions, but you wanted them to be something. So maybe Blade Step was meant to be a blinking teleportation in very high magic-al terms, but as I read it, I was visualizing iaijutsu duels and Kurosawa movies, so it became that. Yes yes, it counted as a teleport, and I could describe why, but it was that, in our game, for my character.

And so we had the Assassin player who gained a power that allowed him to fall from any distance without damage, and it was clear that it was bordering on the supernatural, but he always described it as him using a grappling hook at the last second or stopping his fall with that (honestly suicidal) "I'll stab the wall and hang from the hilt from my sword" move. There was no question. There was no buts.

I mentioned this to Ron before but it became particularly explosive in our last 4E game, a couple years ago, when a player decided to play a Warforged Swordmage. The character concept has its own very specific characteristics (the Warforged is well estabilished and detailed, as a race, and the Swordmage is a known entity to anyone familiar with the Forgotten Realms). So, it should be clear what you're playing, right?

But then he started reading. Lighting Lure – ok, I know nothing about this. Let's read. Useless description. What does it do? Hit at range, deal electricity damage, pull in. If you can't pull in, there's no damage.

And he comes to me and says "I think I have this electrified grappling hook in my arm. This is what this thing is". Corrosive Ruin? Acid thrower. He was quickly going from the intended arcane warrior to some sort of fantasy robotic Boba Fett and it was glorious.

I don't know if it's precisely the point of the discussion here, and I don't know if it was an intended effect of the designers, but I've never seen (before or after) such a positive outcome in having the players fight with confusing, videogame-y names and descriptions for abilities that had such clear and flexible identities in actual play.

You didn't use the thing expecting it to be something. You looked at it in action, and you ever so often had people say "You know, I don't think I turn into a blob with this warlock teleportation power. For my character, a swarm of maggots makes more sense". And it was that, there was no trouble in implementing it, because the "reskin" process wasn't based on expectation but actual use.

Ron, I literally fist-pumped

Ron, I literally fist-pumped when I read the line "listening to the album is not the same as playing the music." I know it's an elementary observation, but thank you for another reminder of what makes this hobby so rewarding.

This core value of the Adept Play community is what made me stop trying to design (which I was doing to overcome my frustration at not having regular games) and start seeking opportunities to play.

To your other points, I think I was drawn to the specific aspect of naming because the titles of Impish Edges were the 'design surface' my duet partner and I had access to in Imp of the Perverse. And even though it's a relatively small space compared to what you can do with points in Champions Now, I was struck by how impactful it was on our play.

I was actually thinking a lot about Trollbabe when putting this post together. I'm experimenting with using Trollbabe's procedures in my OSR Solar Blades & Cosmic Spells duet. A lot of it works brilliantly—designing each adventure around a core set of Stakes, having the PC wander from planet to planet, playing NPCs reactively toward a constantly destabilizing status quo, having either of us 'call' a conflict type.

But one thing I really miss from Trollbabe is the clarity of the scores. In the three games I've played with Manu, calling a conflict has forced me to really think about what I want: to make someone reconsider their course of action (Social), or to bring down the hurt on them (Fight)? And there's a very cool spiral where Social conflicts feel less and less tenable as the game goes on.

The scores in SB&CS do have some distinctions that I like, but they're not as fine-tuned as in TB.

Lorenzo, thank you for thinking out loud. It's enlightening to see all the permutations this can take. It made me think that between the extremes of 'this skill/trait/characteristic is only applicable in one situation' and 'any skill/trait/characteristic is applicable anywhere at all times,' there are infinite possibilities.

Burning Wheel's Fields of Related Knowledge (FoRKS) create a really nice balance between skills differentiation and creative applications. Each skill can be rolled as a primary skill, or "FoRKed" into another skill roll in order to grant a bonus die.

You wouldn't be able to bring your Strength attribute to bear (attributes never FoRK), but if you had a knowledge skill like "Security-wise," and the lock was made by a dwarven master craftsperson, and you happened to have a Dwarven Crafting skill, both those contextual skills could positively affect your lockpicking attempt. Just one example of the infinite ways this can be arranged.

Runequest: Roleplaying in Glorantha seems to have multiple notions of skills/scores at work. Skills can be used as straight-up rolls (pretty familiar). They can also, where appropriate, be used to 'augment' other skills (a bit like FoRKs, but without the carefully crafted interdependencies between skills).

And then there are Passions, which seem to be a bit closer to Traits from The Pool. Calling on your Love (Family) Passion can boost a Skill. It's not necessarily 'because' of anything, though….more because this is something thematically important to your character.

I wonder: Are there terms for describing different 'skill architectures' like this?

One last thing, I think the conversation (training session? mental marathon?) Ron and I had here has some good insights on how the 'rabbit hole' of skill applicability can lead to depths of murk. Ron's analysis might have some helpful language if this is a question you're interested in exploring further (I certainly am!)