Watching the discussion "Dice: the love, the hate, the fear, the need" ( http://adeptplay.com/consulting/dice-love-hate-fear-need ) led me to consider the role of Hero Points in several role-playing games I'm familiar with. By Hero Points I mean a fund of points that a player can spend to influence the outcome of a resolution system that calls for a dice roll.

Watching the discussion "Dice: the love, the hate, the fear, the need" ( http://adeptplay.com/consulting/dice-love-hate-fear-need ) led me to consider the role of Hero Points in several role-playing games I'm familiar with. By Hero Points I mean a fund of points that a player can spend to influence the outcome of a resolution system that calls for a dice roll.

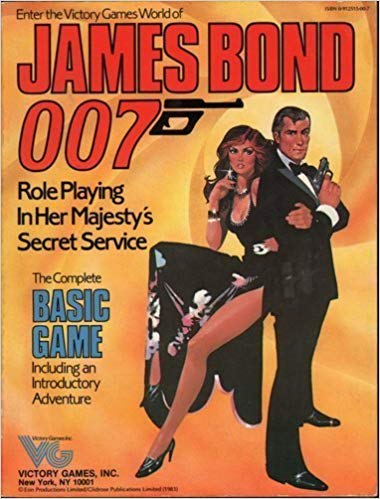

John Kim in his online essay, Hero Point Mechanics ( http://www.darkshire.net/jhkim/rpg/systemdesign/heropoints.html ) lays out a history of early RPGs that used a hero point mechanic. He sites the use of fortune and fame points in the 1980 edition of Top Secret as a precursor, only allowing players to mitigate damage that would take the character out of play. By his reckoning and mine, the James Bond 007 (1983) is the first implementation that allows players to change any task resolution roll.

In the James Bond RPG, a task is resolved by rolling percentile dice less than or equal to a "Success Number (SN)." Degree of success, called "Quality Rating (QR)," is determined by the resulting dice roll: rolling at or below 1/10th the number is a QR 1; 2/10ths or less is QR 2; half or less is QR 3; SN or below is QR 4; and rolling above is failure, rated QR 5. QR dictates details of level of effect, such as wound inflicted or, outside of combat, time required to act, the amount of information gained, or the difficulty of opposing a player character's action. (The Seduction skill, for example, allows the NPC the option of resisting by rolling against a success number equal to the PC's Quality rating times the NPC's Will score [a very neat formulation for opposed rolls!]).

PCs have "Hero Points" that can be spent to shift the Quality one point per point. The text indicates that hero points can be used after a roll to modify the results, with an exception made for "hidden" rolls, where the player must commit points before knowing the outcome. The rules also mention using Hero Points to add fortuitous elements to the fiction, such as finding a gold brick to augment hand to hand damage against Oddjob, or encountering a kid with a can of gas when one's vehicle runs dry during a chase. Meanwhile, villains and major henchmen have "Survival Points" that can only be used defensively.

At character creation, the player characters each start with no Hero Points and gain one each time they roll QR 1 in a noncombat task. Unused points can be accumulated across sessions. Meanwhile, major opponents enter play with a healthy number of Survival points.

For its time, 1983, James Bond 007, was a radical and elegant game design, and remains so even in comparison to modern designs. You can find an almost identical implementation of the games, scrubbed of James Bond references, in the 2014 game, Classified. I think any RPG designer or hacker should have a look.

What effect do Hero Points have on game play in James Bond? Let's note some design choices first:

- PCs don't start with hero points but villains do start with survival points.

- PCs gain hero points by exceptionally good noncombat rolls.

- Villains get survival points just for being villains.

- Villains have no means of gaining survival points.

- Hero and survival points can be spent after the result of a roll is known.

- Any number of available points may be spent on a single roll.

- Hero and opponent can spend points back and forth against each other over a particular result until someone runs out or decides to stop.

The text says that the purpose of hero points is to emulate how the cinematic James Bond manages to do super-human feats or have timely luck. Note that the games referent is the movies. The game was designed during the Roger Moore era of Bond, when stunts were becoming more and more ridiculous. (Having read most of Ian Fleming's Bond books, I can attest that the literary Bond never approaches this level of absurdity — nor, incidentally, is the literary manifestation as misogynistic or womanizing as the cinematic versions or the 60s and 70s.)

An attempt to provide plot pacing, just as in the movies, is a hidden function of the hero point system. (Thanks to Ron for pointing this out in another post). While the text doesn't state it, the design choices support it — Villains start with survival points, while players enter a scenario with their Hero Point supply usually exhausted from the previous adventure. This means the villains have a kind of plot armor against player interference until the players gather enough points to wear down the villains.

GM advice encourages the GM to provide players with opportunities early in play to make easy noncombat rolls that can produce the QR 1 results they need to accumulate Hero Points. Game advice and the published modules all recommend a "teaser," like those in the movies, and then a period of investigation before major confrontations. This supports the accumulation of Hero Points.

How does this affect the experience of play? As my experience of actual play of James Bond 007 was 30 years ago, I only have vague memories. Let me start with some questions for play test instead:

- How does the method of gaining Hero Points affect play? Aiming for a QR 1 (10% of success change) would seem to encourage players to pursue activities with which they have a high chance of success. Does this require the GM and players to work to create those opportunities?

- How do players value the different uses of Hero Points? Do they use them for super-human feats? For fortuitous advantages? What I remember is players hoarding the points to defeat villains or prevent being wounded–but that might also be because I, as GM 30 years ago, didn't really understand the other options. Anyone have more recent experience?

- Does the system produce the experience of a gradual build to a climax? Is it satisfying to produce this effect by spending hero and survival points?

- Does the expenditure of hero and survival points reduce the importance of dice rolls? Do they actually reduce the excitement of players taking risky actions?

Does anyone have memories of how actual played worked for you? What was your experience?

————————–

References

Ron Edwards and Lorenzo Colucci. (2019). Dice: the love, the hate, the fear, the need [Discussion on video]. http://adeptplay.com/consulting/dice-love-hate-fear-need [Accessed 12/1/2019].

John Kim. (2004). Hero Point Mechanics. [Accessed 12/1/2019]. http://www.darkshire.net/jhkim/rpg/systemdesign/heropoints.html

Gerard Christopher Klug. (1983). James Bond 007: Roleplaying in Her Majesty's Secret Service. Victory Games, Inc.

Joseph Browning. (2014). Classified: The Role-Playing Game of Covert Operations. Expeditious Retreat Press.

17 responses to “James Bond 007: Hero Points in play”

Interesting discussion.

I'll chime in since the original post references what I'm working on and what Ron was giving me advice about.

And I need to preface this by taking the subject of my game out of the way before the actual discussion begins, because truth to be told, in my game "hero points" are substantially a fraud.

When I started designing this game I started looking at pacing mechanisms that would work for the intended result – which was that of creating somewhat believable fights with classic fantasy monsters with a good degree of tactical dept and the most evocative descriptions of the actual fiction this kind of approach could afford.

Now, we are discussing hero points as something that influences the outcome of a roll, but in many ways I feel the elephant in the room is another type of "points" that through much different aesthetics essentially fulfill the same function: hit points.

My idea that hit points aren't really anything different from hero points (except, completely passive) is rooted in several observations, but the most relevant here is the fact that the main effect of hit points is that of undoing something the fiction would suggest has happened.

The giant swung his axe, an impossibly large and heavy piece of metal. He hits you. He rolls a monstrous 3d8+5, which is enough damage to cut in half a cow. This is what the dice have told us. But what has happened in the fiction?

You're actually alive. In fact, you've taken less than half your maximum hit point total. You've not spent hero points or used similar mechanics but the fictional outcome has been altered, and we would need to invoke a further layer of description to justify it – you were narrowly missed, barely scratched (by those 600 pounds of metal launched at a swing speed of some 60 mph) or some such. If you want to add more ludonarrative dissonance, assume you've been critically hit by the giant and survived.

Or you failed your saving through, fully taking the impact of a direct blast of acid from the black dragon's breath. But those 47 damages didn't kill you. Or scar you. Or melt your equipment. So what did actually happen? Where you hit or not?

So I maintain that what hit points do is essentially change outcomes, turning hits into misses and fundamentally acting like "passive hero points" you get no choice or say on using.

Basing myself on this, what I did was rather simply turn hit points (a passive, ablative resource) into energy points (an active resource I need to spend and justify – and describe). So now you need to justify how you "spend" those hit points to survive those horrible things, and fiction isn't formed before you do. See how it's a fraud? The core dynamics of hero points is that their use should be exceptional, I think. In my game, if you don't spend energy you will die fast and horribly. Spending some energy is essentially a default state if you want to survive, and the role of bounce is that of forcing you to make hard choices precisely because if you spend them too liberally you may miss them in a moment of real need.

Going back to Bond, there you have hero points as a necessary tool in specific moments of the game (hence, this fulfills the requirement of exceptionality). I have some reservations on the idea of running easy tasks to accumulate Q1 successes and thus "load" your Hero Point pool in anticipation of the big climax – the idea of doing easy scenes to "earn" victory in an harder one is counter intuitive to me, as I would expect a similar mechanic to work on the principle of struggling and getting hurt only to prevail later. It's sort of the opposite of a "death spiral", as good rolls lead you to be safer and safer – and as a consequence, bad rolls probably sting twice as much. Imagine streaking a lot of poor rolls and thus starting the big fight with no hero points. I haven't played Bond so I reserve judgement, but that sounds… miserable.

Trying to answer your questions:

1. I think it does, very much. As I said, the mechanics of Bond seem to strongly inform how the game is played, and without direct experience I fear drawing judgement, but as described, they don't seem to do so in a positive way, at least for me. I think gaining or "charging" such a useful resource should be something that depends on struggle or sacrifice (or even simply resource expenditure) rather than success to feel earned.

2. This is the focal point. I can speak for myself only, but I didn't want players to feel like they need to hoard energy, nor to essentially strategize about it. If you take a look at the most common type of "hero points" traditional games offer – which is rerolls – you will often see people never spending those, fully expecting to have a more dangerous or crucial moment to use them on, or do the polar opposite, which is trying to negate the first blunder of the gaming night (I've been seeing this a lot in my recent experience with Pathfinder 2, people literally blow their hero point on the first failed roll, knowing they'll gain another at the start of the next session).

I'll have to cite D&D4 again (and I apologize if I'm using such a limited and same-ish range of games, but I'm trying to run a comparison between similar procedures) but in that game the hero point (called Action Point) also allows you to gain another action in the turn. And here I've seen much more interesting, conscious and deliberate uses and applications – and I think it's no coincidence that not undoing what the dice have told us but building new outcomes and fiction is a part of that.

So in short the question is: how the players want to spend their hero points massively depend on what the hero points do. And if what the hero points do is undo an already estabilished outcome the dice (or other resolution method) has produced, you risk ending up with them diminishing the gravitas of the dice and causing decision paralysis in the players.

3. It depends on how we want to intend the use of the word "climax". A "climax" is, technically, a progressive growth in intensity. So the mechanics of 1983's Bond would definitely produce a climax – you go from smaller, less important successes to bigger, more important successes.

But the word "climax" tends to be often associated with the idea of "satisfying, bombastic conclusion" and if we look at narrative and narrative devices, I don't think I can name many examples of climaxes that consist in heroes doing better and better until they win. If we want to use excitement as the parameter that needs to be ever-increasing, then a mechanic that hinges on pursuing the lowest risk possible until the final showdown doesn't seem to really work, at least for me.

4. I think the main factor here is whether or not the hero point expenditure is part of the event (or of the IIEE process, if you want) or if it comes after. If you're spending the points as part of the action, as one of the devices that can influence or compensate the effect of the die roll, then you can possibly even increase the importance of the dice. I think it was you who made the example of pushing power in Champions Now: that feels to me as an example where spending points adds to the importance of the dice rolls (also by literally adding more dice and another dice roll, which increases bounce). In my game, energy expenditure is a given – attacks are assumed to land, and you need to spend energy to avoid them, so a really big roll has a strong impact because you need to spend a lot of energy to defend yourself.

Now if the hero points comes after the process and serves as a way to undo that outcome, then you diminish the impact of dice. Massively so, if I may. Again, trying to highlight my reasoning in creating the Energy mechanics in my game: if I'm spending energy on pretty much every hit, a big hit is impactful because it consumes my resources and affects the flow of the game. I'm having to spend hit/hero points to save myself, points I won't have later. If I'm playing a game where I have a good chance of being missed (if the roll fails to pass my AC), and when I'm hit there's another resource that gets depleted (hit points), and I add hero points on top that turn one, potentially devastating hit in a miss then I'm completely undoing that one big "wow moment" caused by the dice, and if we don't allow dice to mess with our plans, then why do we roll them in the first place?

Great post and great opening

Great post and great opening comment. I'll toss in another game title, the little appreciated Extreme Vengeance by Tony Lee (1997), which is based on over-the-top action movies. I think it's a remarkable design hampered by an over-jokey presentation and an inattentive user base.

In this game, you have Guts and Coincidence. Rolling higher is better. Your Guts is reduced by damage, but that recovers with each scene – furthermore, with every defeat, your Guts is increased by 1. So effectively, you get your ass kicked a lot and become tougher and tougher. Coincidence, on the other hand, is spent by use, so that it becomes lower and lower – the idea being, obviously, that as play goes through scene after scene, you will be pumped up on Guts and you're running low or out of Coincidence.

It's especially important that although these two scores affect the fiction very differently, both of them can do damage to opponents using exactly the same numbers, so the difference between two oppositely-built starting heroes isn't a big deal in terms of raw effectiveness. So building one of them to be high at the expense of the other is not a strategic issue.

I bring it up because it's an excellent example of values of this kind being effetive pacers while preserving a great deal of the required genre and allowing for a changing context for mechanics as you play through situations. You will not be surprised that one of my preferred minor hacks for the game is to reduce the number of a given charater's abilities, most of which "buff/debuff," and therefore basically mute this ongoing shift in points. In other words, abilities that keep your ass from being kicked (the general assumption for what abilities are for in role-playing games) are working against the game being fun.

Interestingly, too, there is no equivalent to Hero Points. Most of the fictional representations for that mechanic in other games is already accounted for by Coincidence in action, which is a resolution roll of its own rather than something you spend to affect rolls or their outcomes. I think this supports Lorenzo's description of Hero Points / Hit Points.

Damn, this is getting long. The other game which seems to "purify" that dichotomy of points and fictional effects is Jared Sorensen's octaNe, but I'll return to that some other time if we want to stay with this subtopic.

That’s a good example of a

That's a good example of a mechanic that immediately communicates the kind of fiction it aims at producing. It's more John McClane than James Bond but it sounds a lot more interesting to play.

I also like the concept of Coincidence and Guts having different uses but being equivalent in terms of contributing to damage. Citing (again) D&D4E a lot of people lamented how it was ultimately very easy to always use your best attribute to contribute to offense, but to me it felt like a deliberate and functional choice considering the game's goals.

The note about abilities being something that prevents or mitigates losses is also a tanged that could be explored in this discussion. I feel like a lot of the undesired effects of hero points hinge around the idea of preventing loss or damage, instead of making them survivable and interesting. We often hear people say their game of choice is gritty and realistical and being wounded should have terrifying consequences, only to later find out that since being wounded is a show-stopper, then you have 11 different ways of avoiding the wound itself. Mechanics that turn events in non-events are never good, in my opinion. Something must happen when the dice roll.

So touching for a second on energy, even if you dodged, you had to move, you rolled through the monster's legs, you vaulted over his back, you're short for breath or possibly you still got scratched by the attack. If you parry the ghoul's claws with your stuff, he may still grab your weapon as part of the action. If you block with a shield, you're running the risk of seeing the attack bypass the defence value and thus damage you (and the shield).

One of the first decisions I took when I started designing the game was not having rerolls as possible mechanics or abilities. Add more dice, remove dice, but once the roll started, the fiction moved and there's no rollback. Allowing yourself to accept the idea that you can rewrite the fiction that you don't like removes a lot of the urgency from play, in my opinion. Let there be consequences. Make the consequences manageable, instead of neutering them.

Breaking out the variables

Here’s a look at the mechanical range, at least as a first pass. I’ve tried to set up the list as non-exclusively as possible, so that a game might theoretically be built with any combination of its items (the only exception is the spending/bidding for either side of a resolution, which is either/or).

Here is a crucial point: that technically “hero points” (used to affect the fiction during play) and “experience points” (used to increased/improve a character’s build) are completely different things, but obviously, they have overlapped in practice much more than they’ve been kept separate. So we have to remember that they are different things and that using the same points for both is a specific design decision of its own.

Getting them

Having them

Resolution

Authorities

Improvement

Let’s look at two extreme versions of the possible profiles. For example, if we take first-generation Champions and Champions Now, the profile shows that this game has no “hero points” at all, just experience points.

Getting them

Having them

Improvement

By contrast, see the games with points that operate only during and within resolution and have nothing to do with improving builds, like the Action Points in the original Hero Wars and Energy in Lorenzo’s design for Crescent. Slight differences aside, these both look approximately like this:

Getting them

Having them

Resolution

That distinction seems pretty clear. Although either “end” of this comparison can be customized in terms of what the points actually do and of how valuable a given point is, they are different categories entirely.

However, historically, nearly all games with these features apparently overlap resolution effects and build effects pretty strongly. That overlap seems very intuitive. By the time James Bond 007 came out, tables were already “burning experience for a bonus” across multiple game titles whose texts didn’t include it.

That’s still standard design right now. When it’s relatively unconstructed, i.e., you can gain tons and tons of them and bank them however long you like, choosing between burn/build indefinitely, then you will run into the inflation problem. The effect then is to demolish the dice entirely, as characters are expected to have a pretty big wad of points, and play becomes simply a matter of who has more rather than who rolls what. Both Marvel Super Heroes and DC Heroes are vulnerable to this effect, and FATE has turned it into an apparently intentional design feature.

The solution to that seems to be to clear or limit the gain of such points pretty tightly. For example, the current HeroQuest (source reference document) assigns you 3 to begin a session, which you may use for affecting resolution through competitive spending or for building, but which clear at the end of every session. That is, whatever you don’t use for affecting resolution, you use to build, every time you play, so there’s no banking.

So I ran my own system

So I ran my own system through your list to see if I got the same results as you did (given all things I still haven't introduced in our talks) and the result is remarkably similar:

Getting them

Having them

Resolution

So yes, it's pretty much the same.

But since the internet ate my reply to the post under the consulting post (my fault, I tried to link the picture of a Batman cover and the browser died) I'll mention something here. I made a few mistakes in running the encounter during our little test. One of them, possibly the most meaningful, was golden-ruling my own game. Kind of, anyways. You asked me if you could use energy to increase the intensity of an action and I let you do so; I did so because of two reasons. The first is that initially that was how the system worked, so it would still be interesting to see that at work in a blind test. The second is that… everybody asks to do that. I think it's the name "energy", or the natural assumption of how such mechanic is meant to work. So I rolled with it but in the current incarnation of the system you do not use energy as a resource that fuels you actions; it's simply how you defend yourself.

This is due to a couple reasons. The first is that when you let hero/hit/experience points do too many things, it's extremely hard to strike the right balance in what is the best use. Now, on a situational level this could be a good thing, as it rewards good decisions and clever thinking. But I could already see myself (and thus others) pulling spreadsheets on how and when it was best to spend points and where per class and build and… I don't want that. There's a good degree of system mastery already looming over the ruleset.

The second reason is decision paralysis. If you have to account for the energy you'll need to pull that one maneuver or be fast enough after this turn on top of managing your survival you end up spending a lot of time thinking about your next move. One of the principles behind a few of my design choices is trying to break the curse of "I did my turn, now I wait 15 minutes for everyone else to go" that plagues so many games I do like in terms of actual play mechanics. Compartimentizing resources feels like a good way to make sure you only have to take one decision at a time.

Incidentally, I never particularly appreciated the entire process of burning XP for bonus (which was however very prevalent, expecially in the 90s – I remember people burning dots in VtM to manifest powers they didn't have and a specific case of a D&D3.5 game where a person playing a cleric burned enough xp to bring him back one level to exorcise an NPC). I can hardly imagine something more frustrating and paralyzing than having to decide if I want to do something useful now or become stronger later.

Small fake edit: as a

Small fake edit: as a clarification, you still get to put extra effort or go for increased effects in your actions, but you do so through dice (you scale down/lose some dice before rolling based on what you're trying to achieve, or scale up but take a hit in terms of windup time).

Ron mentioned Jared Sorenson

Ron mentioned Jared Sorenson’s Octane, which I’m not familiar with, but one other Sorenson game that would be worth considering in this discussion is Lacuna with its heart rate mechanic. That system has some elements in common with others in that it allows players to add additional dice to their rolls, even to the point of guaranteeing success. Aside from these similarities, there are elements of that mechanic that seem sui generis.

A quick summary: Every time you roll the dice, the total not only determines whether or not your action is a success, but it also gets added to your heart rate. When you enter your target heart rate, you get to roll as many “bonus” dice as you want, and you become capable of superheroic feats. The system is diabolically generous, because those totals also get added to your heart rate, and they push you to your maximum heart rate zone, where things become perilous.

The heart rate mechanic definitely impacts the pacing of the game session and it impacts player decision making throughout. Players try to control the pacing and build up: They don’t want to get into their target heart range too soon, because they want to save it until they are encountering a major Hostile or need to accomplish some other crucial yet riisky feat. And if things get fast and furious in that encounter, agents find themselves walking on water in one moment but then gasping for air (and threatening to go into cardiac arrest) a minute later.

One curiosity is that you know you can achieve that target heart rate (and all those bonus dice) simply by going out and doing actions that will require rolls (whose totals get added to your heart rate). But being in that target heart rate area has the player walking a tightrope. On the one hand, they get to decide freely how many extra dice they want to put into a roll, but they know that the more they put into it, the more quickly they will land in the heart rate danger zone.

The mechanic encourages tight mission-oriented sessions and it is quite successful at building to a climactic make-or-break scene. If a couple miracle moves are not sufficient to take down the Hostile, the characters are either pathetically grappling toward an extraction point or they are meeting some suitably grim end.

5th edition Inspiration

in Consulting, Tor Erickson and I discussed D&D 5th edition’s Inspiration Points at some length, as he had noticed that players weren’t excited by getting, having, or using them, but they were very excited by experience points. Ram Hull had also grappled with this issue and arrived at a cool solution in play, and Tor adapted it into slightly different form and discovered remarkable success with it. I suggest checking it out in detail, including the conversations along the way:

Proto-concept from D&D play

Everwhichway: Valley of the Defiled

To crawl or not to crawl

The merchant’s wife

Manticores R us

All of these were made in the early days of Adept Play, so the videos are variously crappy, and they are very long, not sectioned into little pieces. So it's not possible for me to direct you to the specific points about Inspiration, unfortunately, and it'll be a slog to find them because we addressed a lot of different topics. You may also be sad to know that one of our sessions didn’t record well so is not available.

I think, though, if you start just by reading the comments, you'll see enough to get the idea of what Tor eventually did and what he learned from it. The take-home is that role-play your guy to get points to spend on bonuses to mute the dice is not fun, whereas get a group-accessible pool of bonus-making points via accumulated individual fumbles is very fun.

I did a little review to

I did a little review to sharpen up this comment. Also, Ram's and Tor's different versions confused my memory a little. So here's what Ram did:

Here's what Tor did:

and

Is the hero point system that

Is the hero point system that Tor describes — earning points for succeses — the same mechanic that he says that they ditched later on?

Also, I note that he says they were earning points for succeses and spending them at a 5 for 1 ratio. In the Bond game, the hero points are earned by rolling 10% of success chance and spent 1 for 1–which ends up with a ratio of 10 for 1.

I wonder if there would be any difference in the experience if points were earned for failure rather than success? The closest I've experienced in actual play is Dungeon World, where a failed roll earns 1 XP. That always added a touch of excitement to failing.

The system he ditched was the

The system he ditched was the existing/textual Inspiration Point system in 5th edition. For a couple of sessions he was using his 5:1 counters in parallel with it, then the Inspiration Point system sort of faded out.

I agree about the failure/fumbles as the criteria for gaining chips, which I think I mentioned or suggested during the conversations with him, but then I was surprised when he turned out to accumulate them via critical hits instead. I guess either way works, but I would definitely like to try the former way some time. I've seen a few different versions of that concept in the past but there's something pretty pure about Ram's implementation and Tor's derivative here that seems more functional for it than the ones I've seen or tried before.

But what are they?

Robbie's mention of Lacuna reminded me of a certain subtopic: whether the hero points "mean anything" in fictional terms. Or to put it a little differently, do the characters know they're using them. If the answer's yes, then something fictional is getting referenced.

At first glance this distinction looks very important. One might even suggest that it represents the hard line between being "hero points" at all, as opposed to being ordinary representational mechanics. It's usually coded with the hobby term "meta."

However, I maintain this distinction isn't particularly important, or rather, that the system in question works the same either way, regardless of whether the point-spending is fictional.

That's why you may ask "but is James Bond really that lucky?" meaning, is it a quality inside the fiction, but you will not, cannot get a straight answer. Because the answer lies in the fact that the word "really" does not apply, and that all activity by any fictional character, for any medium, determined however you like, is "meta."

It's also why you can find so many blurry versions in role-playing systems, as with the Action Points of Hero Wars. You get X many based on whatever ability you're bringing into the contest, so, if you have 2w2 in Axe Fighting, that's 42 points. Every action you take risks some or all of them, and a few results save or gain a few. So arguably, they're your character's endurance for the fight, right? Except that it makes no sense that you'd have more energy for axe fighting instead of, say, Running, which is 5w on your sheet and therefore you have 25 points if you were using that instead. You should have the same energy either way, right?

The logic is therefore not in-fiction at all; the point is that you are better as a story entity with axe fighting, and that's what we came here to see you do; being a little worse at running (well, not that bad, as 5w is pretty good) is aso part of what we came to see. Being good at axe fighting in the fiction is merely a subset of that "story entity" quality.

Let's keep going with the Action Points, with the side comment that I am rather upset that subsequent versions of the system eventually phased them out. They can also be donated to others, usually narrated as tossing someone an axe or otherwise being helpful; this is distinct from rolling to help someone via the assist mechanics. Assisting gives them a bonus on their roll; donating them Action Points is much more direct and very, very consequential, typically keeping someone alive and permitting them to put more punch into the final outcome of the contest. So … what are they representing there? Time? Opportunity? Awareness? The answer is not "all of the above," but rather "whatever works." You adjust the fiction by using the points, but you are expected to do so, and it's very enjoyable to do so, rather than just spending the points.

Which is what you do in James Bond 007 too. You spend the points, and boy, James sure got lucky this time! Or (watch me now) he was very very skilled after all, "no one but him" could have made that shot, etc. See what I mean? Spending the points is more fun when it's specified in the fiction, and it's specified in a way which matches both that character and those circumstances, but there is no absolutely fixed fictional reference point for that expenditure.

So specifying the points in Lacuna to heart rate and the time-position shifting in Circle of Hands to Brawn is merely the most hard-edged version of the same thing, because they are translated into actual damage or highly-potential damage for the character. It seems like that makes them non-"meta," but the fact is that the player is still deciding whether they get spent or not. Again, it's all meta, so never mind that issue – instead, all we're seeing here is that (i) in some systems the hero point expenditure has more specific fictional reference than in others, and that (ii) in some systems, the expenditure has more toothy costs than in others (the minimum being "you have less points for later," and the maximum being actual damage).

My claim is that these distinctions are nuances of the same thing rather than being on opposite sides of a hard line of defined separate practices.

See, this is the most

See, this is the most interest part of the entire thing.

And I tend to generally agree: trying to draw a precise split between in-fiction and meta justification for the expenditure of such points is probably just an exercise in frustration or vanity. The various systems may tilt one or the other way, but I can't think of a single system where there's a perfectly consistent in-fiction explanation for the use of these points.

And I'd start with mine, because this is a big thing for me: the origins of the Energy mechanics are more or less rooted into two factors, the first maximizing player activations by letting them play out enemy attacks, and the second moving from "I lost some of my points because something happened, but it's really hard to make out what" to "I need to know precisely why I am not dead".

So with that premise, and the way points work, and how the game dictates that your energy point expenditure needs to make sense in-fiction we should be clear, no? The points represent reflexes, conditioning and all that jazz and characters are fully aware of what they're doing with them.

But then we get to things like the Shield spell, an arcane ability that generates a small pool of energy the caster gets to spend to defend himself for the spell's duration, and well… what are those points then? Are they the same thing they were before, or this just shows that the Energy pool is ultimately a meta-narrative currency with strong (but nowhere near exaustive) in-fiction presence?

And I get to the point where I say: "Who cares?". If the mechanics don't trigger disrupting ludonarrative dissonance, then why obsess over meta element? Expecially when (and forgive my uncharitable take here) the people who generally are most vocal about the need to have zero meta elements in their game are D&D players who claim hit points are meat points.

James Bond: Hero Points and IIEE posted to new topic

http://adeptplay.com/actual-play/james-bond-007-2-hero-points-and-iiee

A bit of follow-up on roll-adjust vs. build

I wanted to follow up on this point of Lorenzo’s:

It's strange. There are games in which I think the technique is very badly suited, for example, any version of Champions, any of my own games, and the early version of D&D that I like (Holmes ’77). And I think that if I’d never encountered it, and read what you wrote here, that I’d agree, that I “would imagine” it to be awful.

However, in some games, this very trade-off is enjoyable as hell. I am thinking about Hero Wars/HeroQuest especially. Why?

One element is the process of acquisition. In the early version, each player gets 1 at the outset of a session, in addition to whatever they’ve retained from previous play, and a whole bunch of them at the end of each session. So even if you use up all the points (either way, adjusting rolls or building), you’ll have one to start a session, to “get out of jail” if you will, no matter what.

The tecchnique wiggled a bit during the development through editions of the game. In the latest version of HeroQuest, it’s almost fully reversed. You get 3 to start a session, and there are a couple of ways to get them during play too. Significantly, whatever you don’t use at the end of the session is erased, so, basically, build with whatever you didn’t use, because you don’t bank points, but will only ever start with the standard 3 at the start of a session.

Fortunately, too, my recent return to The Whispering Vault is instructive, because it works entirely from the other end. It has a somewhat pure form, or rather, based on previous frameworks of game design, in that you get 5 Karma to start play, then from that point forward, it’s simple arithmetic based on what you get at the end of each Hunt, and what you use to adjust rolls during play or between sessions on improvement. The key, though, is that at the end of a Hunt, you get a lot. Not just a little drib or drab, but a nice healthy 6 to 9 points. You can see it in the players’ faces and phrases at the end of my recent game, available here: they say, “Oh! You spend hard, but you gain hard too!” So it’s OK to improve a bit and to keep a bit; you don’t feel the crunch to the extent that it harms your decision-making, even though the trade-off is real.

So although there’s technically a trade-off, and the “uh oh” you feel when you’re out of these points during play is real, for some reason it never feels like a sadistic-choice trade-off. The whole thing becomes fun, because in all three of these examples, a kind of cognitive (rather than numeric) balance has been reached so that the spend-or-build decision isn’t trivial, but it isn’t lose-lose either.

After 20 sessions, I observe

After 20 sessions, I observe that the Hero Point system in James Bond has a couple of effects:

1) it encourages players to seek opportunities to use noncombat skills;

2) because 1 HP only shifts success one degree and there are five degrees of outcome (Failure, Quality Rating 4, QR3, QR2, QR1), it's cheap to move a failure to a basic success, but can be costly to generate a critical (QR1) result;

3) because HP can be spent to mitigate damage, there's a constant tension between "should I spend for my own success, or should I save this in case I take damage."

4) Because one only gets HP at character creation and then only for QR1 rolls after that, they are scarce and highly prized.

Also, some NPCs can have Survival Points, which can only be spent to reduce the results of PC actions directed at them. That means that using HP directly against villains is not cost effective.

In a recent session, Rod's character ran out of Hero Points before he got to a safe he wanted to open and had to accept the skill roll failure and then survive escaping the compound without HP to reduce wounds from his pursuer's weapons. He got out, but was pretty beat up — and wounds impose a pretty substantial penalty on any dice roll.

I agree with all of the above

I agree with all of the above. To add some more interesting examples:

-A Persuasion roll, to gain the agreement or compliance of an NPC, is a very common interaction in this game. When you roll, you know what your QR is — and can bump it up with Hero Points — but the result doesn't *mean* anything until it's cross-referenced with the target NPC's Willpower, which you don't know but the GM does. So HP spent here could end up providing little more than reconaissance value ("This guy must have a pretty high Willpower, I guess"), which is a marginal use. But the more you learn about the NPCs you're interacting with, the more you'll be able to target Hero Point use where it has serious leverage.

-The way HP interact with gun combat is also interesting. Here, you can use them to ensure a Wound, but the target's Willpower (again) determines their chance of struggling through the pain and continuing to act against you, with you as the PC having no ability to affect that roll (apart from having caused it). With a sufficiently powered weapon though (rifles and above, mostly), the gargantuan investment of 4 Hero Points can guarantee a kill — except against NPCs armored with Survival Points, as Alan points out above. (That hasn't come up during my time with the game — it may have for Jon and Alan in previous sessions)

-We're playing what the books call an "agent-level" game, where the PCs are relative small-time operators. If you wanted, you could play 007-level characters with gobs of Hero Points to start with, and generally better chances of getting more during the game. I have no idea if that kind of play finds its own balance in terms of challenge, or just becomes a too-easy romp.