Second session for Legacy, this time ramping the soapy feels for Alan’s character, Mike, up to that number you know, and to my great pleasure, outdoing King Cinema Himself in sheer power of the spectacle. “Iconic” doesn’t begin to do it justice.

Note to self: I swore that my three-plus hours play session days were over. Damn it! I used to run two-hour Champions sessions using full-on combat mechanics for four or five players, and those were hard-hitting baths of soap opera and fights. That’s where I learned Bangs. What the hell is wrong with me now? I have got to recover that skill, use it, observe it, and figure out how to explain and teach it – fast.

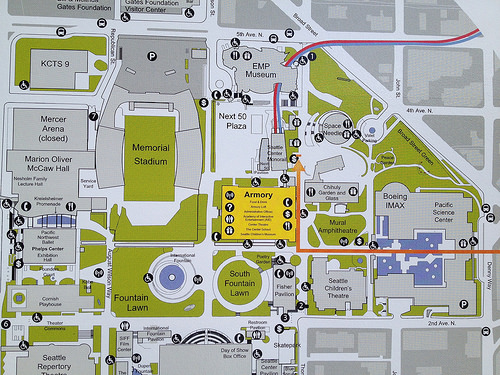

Part 1 is below, concerning our heroes getting to Seattle in their plan to talk to Darius Darkstar, last seen in critical and mysterious condition at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. A scheduled dinner for Mike seems a harmless reason to delay briefly, and for Vince to take in the sights at the Seattle Center.

Part 2 concerns the Dark Cohort deciding to add themselves to the mix. I talked them up a bit in Part 1, apparently successfully, as the players were extremely spooked. In creating them, I stayed with our guiding statement that powers were “bright and fun,” tuning that principle for some of the scariest-out-of-the-box villains I’ve ever come up with.

Here’s Rod’s picture of PowerStar!

Here’s Rod’s picture of PowerStar!

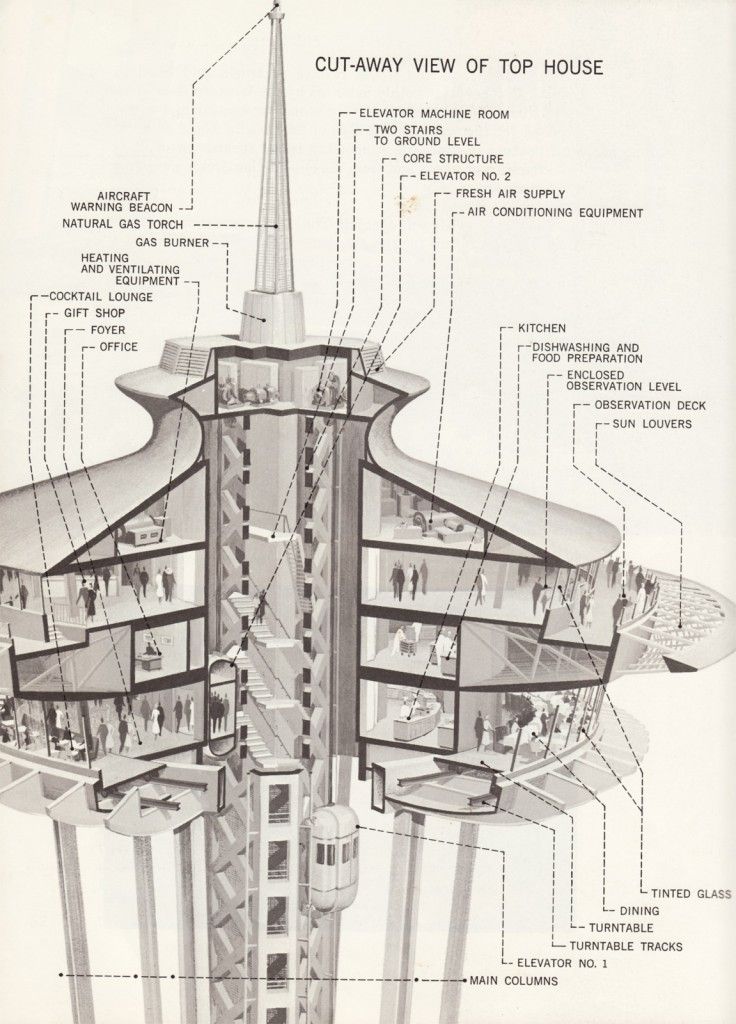

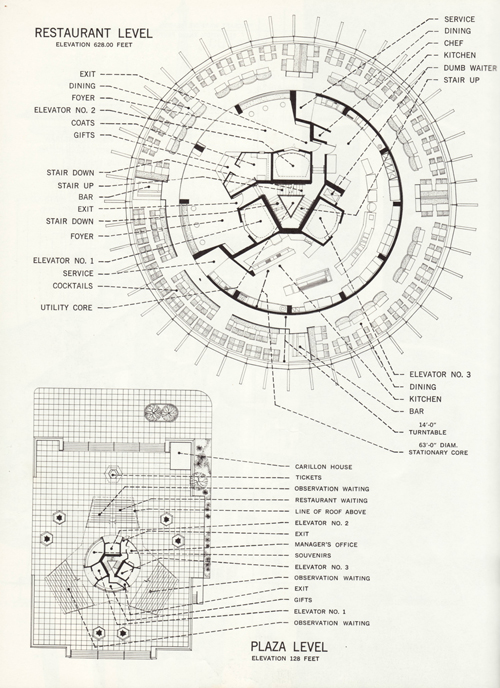

A couple of observations: first, a huge win for the mechanics in action, as you’ll see several different powers, the fatigue mechanics, and in-fiction weight and mass all interact strictly by the book for a genuinely nail-biting and ultimately fully justified outcome for the Space Needle.

It does lead me to reconsider some things about both Growth and Density Increase in terms of conferring extra Endurance, but as far as how either affects things in play, I’d say the old standards, which I’ve preserved, are truly fine.

The other observation concerns location, confirming yet again that player knowledge of the location plus ordinary maps leads to completely playable situations. I’ve included a couple of them as attachments, which will make it easier for you when they flash on the screen.

31 responses to “What has the Space Needle been doing all these years?”

WhoDo We Fight?

So, I'm still in the middle of watching this. But when Ron is talking about "Who are our adversaries?" as a major component of a team's self-definition, it gets me thinking of "the PCs share a Hunted" as a starting point for play.

When my reply turned into a

When my reply turned into a universal list of all relevant super-teams in comics, including members' names and publication/economic context for each company at the time, and when I realized that was only the introduction, I decided this general topic needs to turn into videos, possibly video discussions, and eventually into a blog post.

The problem for a simple reply is that almost anything one proposes that's not "totally no" is viable, but then, as a reply in principle rather than an example in practice, it needs its own special array of qualifiers.

That's why I keep saying this is easy in practice, you just say something that seems doable relative to the two statements, and which everyone can run with, and see what happens. The danger is not the failure to find some anchor, but the temptation to overdo it, qualifying and negotiating and world-building, ultimately playing before play and rendering play drained and routine. But a technique which strongest when it's most minimal is a real pain in the ass to describe, explain, teach, and convince to use, in text.

Maybe that's related to my general outlook that playing Champions produces a single superhero comics title, not a comic that encapsulates anything and everything. But there are social and creative issues tied to this game specifically, too. I'm getting the idea that a basic unifying statement is frightening somehow: it must have consequences, and we don't know what they are yet. It also seems tied to an embedded belief in Hero System culture that players are up to No Good and must be prevented from doing or calculating anything that's not been vetted and approved to the Nth degree.

Anyway, I'll get to work on examining superhero teams across comics titles, game texts and rules, and play techniques. It's a big field of study.

Secret ID made me sweat

I really felt the dilemma of keeping a secret around minute 49 and following, having to negotiate between my personal aversion to lying tied with my conception that Mike is a decent guy) verses the pressures of maintaining a secret ID. I want to develop Mike's reasons for keeping a secret ID. Also, there has to be compelling practical or external reasons for the restrictions on the money use too. Not sure if all of this is within the scope of the number of sessions we might be able to play.

Mad Restraunteur Skillz

I'm pleaased how this background was userful last session. I envisioned that a 20 something who owned and ran a successful restaurant would need to develop leadership skills, which could then be useful in a superhero persona.

It was amusing that it showed up again in this episode ( 1 hour 8 minutes) where I decided to try to infiltrate the staff area of the Space Needle restaurant to find a place to change into PowerStar. Had I been thinking about probabilities of success, I probably would have change tack as soon as Ron said it was a Disguise roll (a skill Mike doesn't have). However, I've learned that there are times in roleplaying games where committing with a "damn the torpedoes" attitude can produce very fun outcomes — a success feels spectacular and a failure usually generates interesting complications. I think the old idea of "step wrong and die" from some old dungeon crawl approaches to play still linger as worries for players, when in fact player characters in most game systems are pretty resilient.

At age twelve or so, my

At age twelve or so, my friend and I were taken on as busboys for a day at a downtown Monterey restaurant owned by a friend of his dad's. Sort of a "get a taste of work" lesson, I guess. I remember it well, especially that we were trusted to carry a wad of cash some place, which impressed us greatly.It now leads me to speculate that we were mules; restaurant economics can be very grey, and my friend's dad was a shady Teamster, which in the 70s were mightily so.

Not long after, at age fourteen, I had an actual paying job with hours & & payday & everything, again as a busboy, at a pretty good restaurant in the same area. I credit the experience with cementing my determination, originally conceived at age twelve, to get out of this town, get a real education, and thus never to have to work restaurant or related services again. It was not intrinsically wasted time, either, as I learned an immense amount about nearly everything, not worth going into here, and I submit that everybody should have this job or one very like it, early in life. As it happens, I gave this speech to my kids, aged 11, 11, and 9, just yesterday.

That sphere of work is profoundly not for me on the basis of raw capability, meaning something I totally lack. There are people who thrive in this work, as owner or manager or head waiter or cook or some combination thereof, and I regard them with a fair mixture of awe, especially for those who own, manage, and function inside all at once. But also with a lot of curiosity about how anyone could possibly want to do it. It is serious work, labor of all kinds, at all levels, and also a bewildering mix of theater, chemistry, people management, business acumen, political/community engagement, and more. It is strangely idealistic and pragmatic in a combined fashion that requires a new word.

Upon decades of thought and observation, I think it has something to do with the utter concreteness of the business: at the end of the day, indeed, upon every hour, you know whether you are ahead or behind in immediate economic terms, and also what that means for your property payment, your taxes, and your periodic assessment of continuing. The corresponding utter clarity of potential failure, which is I think a nearly intolerable experience for many people, can for others be very welcome.

I relate to that clarity, if not to the required tasks and talents, and so Mike's character concept does fairly invoke for me an immense range of experience and insights that he can apply to many, many situations. Fortunately it does for you too, so that we seem to meet pretty well in play for things he could/should do.

In rules terms, this is much more interesting than it might seem at first. "GM's call" is not precisely what goes on in Champions, and it didn't in our game. Let me lay it out carefully, because Mike's two restaurant-relevant situations so far are going to be examples in the text for sure.

First, as I keep saying, a great deal of a character’s skills and other features are not rated in points, but are implied by brief descriptive phrases, brought into play through a variety of scene framing and related interactions, and invoked as actual abilities in crisis moments. To use those, the Intelligence, Ego, Dexterity, and Perception rolls are available, and a given hero is sure to have a rather good percent in one or probably more of them.

Second, there are the listed skills – Climbing, Computer Programming, Detective Work, Disguise, Security Systems, Stealth – which are by definition over-the-top, comic book-y versions of these things. A professional mountain climber character doesn’t need the Climbing skill in Champions and would reasonably get those four rolls for doing anything perfectly sensibly associated with that profession; but anyone with Climbing can do some crazy shit with climbing that is only really expected to work in comics and certain cinema.

So perhaps you can see my in-play question as GM in this case: whether Mike would get an Intelligence or perhaps Perception roll to fake being staff at the Space Needle long enough to get to the private staff area; or whether I’d require it to be a Disguise skill roll, which in this case he happened not to have.

The simplest solution is the first: give him an Intelligence roll (which corresponded best to what Alan said Mike did) and that’s that. I might even recommend it as the best practice. However, in this moment of play, I went with the less generous option, with the mechanical call of a 9 or less roll.

You see, that category is very narrow in this game: attempting a skill you don’t have. In nearly every imaginable situation of play, it’s simply not allowed. You don’t have Disguise, so when you try to pull off Disguise things (remember, this is crazy comics/movie Disguise), you fail. Done. There is hardly any room for the unskilled attempt at a Skill that might actually work.

Here’s my thinking: if the issue concerned ordinary behavior concerning a restaurant, or (as with the situation in Darius Darkstar’s cell in session 1) a crisis that may well occur in a restaurant, then Mike should get the former, probably with his best roll of the four as the player would probably choose actions that corresponded to it, and therefore a pretty high value. But since posing as staff at some other restaurant isn’t typical or even really imaginable as something one would have worked at doing, I decided that his prior experience justified the attempt, but that the lack of the formal Skill needed to be acknowledged.

As it turned out, play then brought a low successful roll and a Moment of Awesome for Mike, which is fine. But I wanted to addresss why that roll was shooting for a 9 and not something well on the other side of the 3d6 curve, and why that situation is not typical for playing Champions. The curious breadth of the restauranteur concept is the only thing that brought it into our game.

The question of secret

The question of secret identities is a very, very good one, but it can easily fall apart when too many of the variables are considered at once. Here are a few of them, which I’m offering because my real question to you, in a moment, concerns your recent reading of the early Spider-Man.

Variable #1 concerns the origin and history of the concept, which lies in non-comics and sort-of comics of the 1920s and 1930s. In these, we’re talking about vigilante gunmen and mystics, who operate in a weird combined space of alienation and patriotism. It has a lot to do with anti-immigration and militarism when you blend both with fetishizing exotic stuff (especially “jungle” thanks to Burroughs), which is sort of depressing; and it is also thoroughly anti-establishment at the same time as being “tough on crime.” It is certain to baffle traditional analysis insofar as the protagonists range way up the wealth scale (I suspect a Scarlet Pimpernel influence here), and even more so when you get into comics proper, in which the female heroes are as intense and sometimes as bloodthirsty as the male ones. If I had to pick one character who manages to correspond with later comics best, it’d be the Phantom.

All these characters had secret identities mainly because “taking the law into your own hands” is frowned upon, including what most of them were doing with said law or rather lack thereof. They didn’t stint on the dark side of the combination of features and some went very far with it; no one ever wrote the Shadow or the Spider as anything but stone crazy, and that’s how the readers liked them. A less grim version of the concept was that one’s “old life” is effectively gone, and that the anonymity is basically strategic – that’s where the Phantom’s at and where most of the very early comics superheroes went with it too.

So I’m saying that comics superheroes inherited the concept of the secret identity rather than requiring it intrinsically or benefiting from it specially, and that a lot of the time it made no sense and no one cared. It was played for laughs for Superman and Batman as soon as those characters sloughed off their edgy beginnings – less than a year.

Variable #2 concerns when and if comics writers felt like considering it seriously at all, which was perhaps discernible in the late 50s Flash reboot (Barry Allen, written by Julius Schwartz). Stan Lee’s work, beginning at the same time with the Ant-Man and the Wasp, tended to go all the way in jettisoning it, first with the Pyms and then the Fantastic Four, the Hulk (after a confused bit when no one knew), and Doctor Strange.

In order to keep the convention and play it for drama rather than jokes, you had to work more from a strong sense of personality for the hero and for the circumstances of acquiring the outfit. Arguably, if Lee hadn’t struck gold with this in Spider-Man, then the convention may not have been repeated so consistently with Iron Man, Thor, Daredevil, the revived Captain America, et cetera. Again, for argument’s sake, I suggest those characters didn’t benefit much from the concept so much as milk it at second-hand, and I point again at many characters at the time who did no such thing, especially the reformed villains like the Black Widow, Quicksilver, the Scarlet Witch, and Hawkeye.

A useful example: consider the very similar original X-Men and Doom Patrol, for whom secret identity made a lot of sense in the former and public identity made a lot of sense in the latter – because in each case, it was explicitly a choice.

So for this variable, I’m saying characters are pretty easily distinguished among these options. Keep the convention due to consumer idenfitication with its longer history (e.g. most DC characters), so either never touch it in story terms or play it for laughs; abandon it entirely so the person and the hero aren’t firewalled (many Marvel characters); address the convention with some care and drama, as with the two “outsider” teams and with Spider-Man; imitate the third option without much intrinsic power (many other Marvel characters).

Whew. Therefore, for purposes of discussion here, and with a sharp eye toward that rarest and perhaps most dramatically-rich position in the above spectrum, I really would like your thoughts on the early Spider-Man as you’ve been reading it, as well as on your own hero’s, PowerStar’s, secret identity. Whatever comes to mind, although given what you’ve mentioned already, lying certainly seems relevant.

And it’s really only Spider-Man we need to consider, and a very limited subset of his comics history at that. Let’s acknowledge, unless anyone can demonstrate differently, that Superman’s 1940s and 1950s lying to Lois Lane was basically comedy with a wink to the reader that this way we’re dodging the obvious but forbidden fun of them having sex. Whether Batman and Robin were gay camp at the same time or not, I leave to lit crit, but at the very least, one can say the secret identities were played for fun and nothing more. Let’s also acknowledge that almost every other superhero secret identity is poorly conceived and relies heavily on the conventions rather than on justification or on dramatic potential (the only other good one I can think of is the original Luke Cage).

So … Spider-Man deserves some thought in strictly textual terms, for this single title written as a single story, no connection whatsoever to other media or franchise identity at this point. What do you see there? What do you think might be relevant to your concept of PowerStar especially two sessions in?

Keeping in mind as well that to change the Disadvantage, all you have to do is shift some points around, which is pretty easy to do. So for Mike to retain the secret identity is very much a choice on your, the player’s part.

(editing this in) Also, consider that many or even most characters with secret identities do include a few people in on the secret; i.e., you could keep the Disadvantage as is and still "come out" to specific people. It doesn't mean you have to lie to everyone, but it's also true that if you keep it as a Disadvantage, you're still not "out" to society at large and most other people you know, and it'd be useful to think of a reason for that.

Peter Parker’s (Spider-Man’s) experience with secret ID

I’m presenting my thoughts

I'm presenting my thoughts not to argue, but for comparison, and I don't think we're disagreeing even though it may sound different. These are observations of that part of the story (and positing that the Lee issues through #100 are a completed novel with a final ending).

What we're seeing, I think, is him catching up to his age, from being a bit infantilized as a kid, and also, instead of meeting peer-group expectations, exceeding them and moving on. Certainly by the #20s, he's ready to be done with high school and the more clued-in peers notice it, like Liz Allen.

There's a certain validity to protecting Aunt May's sensibilities, but I think that this justification wears thin after a while (she proves to be a tough ol' bird later) and most of his others were weak from the start. I don't think it's genre convention; I think it's good writing. Peter is becoming a man but he isn't yet able to admit he is, not to mention having trust issues that would sink a battleship, and walling away Spider-Man from himself is more about those than it is about any objective dangers. So I think he lies to others in order to keep on lying to himself.

It's even good enough to pull a full reversal on the historical convention: that instead of being a vigilante (in the more violent and antisocial meaning of the word) who wears a mask to hide his identity, hiding his identity makes it possible for him to become a vigilante, certainly as perception and to some extent in actuality.

I have to jump ahead to say that I wouldn't be so fixed on this if it weren't for the remarkable build and payoff that continues for several more years of comics, until it's obvious that Captain Stacy knows the whole thing long before he says so, and also obvious that Gwen would have accepted the whole story – it's his lack of trust that drives a wedge between them, not the "truth." I also suggest that the key antagonist throughout is the Lizard, not the Goblin (granted, a close second), because Connors' family knows he's a monster and loves him anyway, a flat-out example that Peter's excuses are not automatically sound.

But I'm getting ahead of the parts we're supposed to be talking about. My position is that for this, the standout example of a dramatic secret identity, the driving components are specific to a somewhat stunted teen who discovers he's super, and concern which aspects of his maturation he can bring into his social identity and which he can't. In other words, the driving components are not external at all – he does have a choice.

I’ve just finished watching

I've just finished watching Part I. Here are some thoughts:

* It was really interesting to see the Disguise ruling in action. Would you have done the same in Alpha, Ron? How about old, 1980s Champions?

* * Also, one thing about the system (well, the systems) that I haven't learned yet is whether you can have "more" of a skill or not. I think it's simply a matter of me not having read it closely yet. But if you do want to answer, I wonder if one can, like, be extra Stealthier or something. I remember being confused about that in our game – it took me a while to realize you don't buy Stealth up to a certain level, which would modify the target number – you just but it, once, and it's at 15. Or I think I realized that, I'm still not sure.

* * * Also-also, what's the purpose of separating Skills and Powers? If you're so inclined to go even more on this tangent.

* I 100% would eat at that restaurant, if I ever visited Seattle. I didn't even know you guys had a restaurant there! I wonder if rotating restaurants are more common in USA, because that alone for me would be a selling point, clichéd landmark or not.

* I'd like to know more about the pacing of having the restaurant conversation be interrupted, at that point, by the appeareance of the villains. Is this just GM fiat? Was there a roll involved in making them appear before the other guests showed up? (Other guests= the investors or whatever that were going to sit down with Mike, his brother and his wife.)

* If I were Powerstar, I'd just say I'm taking the money to help me grieve the loss of my partner to my own brother, haha. Alan has really cooked up some good drama there! That could be a TV show all on its own. Running a restaurant with an ex, who's now married to the brother.

* We're seeing a process that I think it's really interesting: Ron introducing supervillains to the other players, that their characters know but they themselves do not. I'd love to know more about this, though I'm not sure how to phrase a meaningful question.

* * This, I can phrase: At the table, is there a knowledge/consensus about whether Advance has interacted with the Cohort or not, in the 80s? Or at least the members at that time. I wonder if you all three already know this, if it's up to Vince's player or Ron or both, or what.

Santiago, if I’d known

Santiago, if I'd known rotating restaurants were a draw for you, I'd have mentioned there's one in San Antonio!

The revolving restaurant

The revolving restaurant/tower is a truly Space Age artifact, fully folded into such things as Sputnik fear ("it's watching us!"), monorail trains with molded plastic seats and kitchenettes, Asimov-style science fiction, and Tomorrowland of Disney fame. The first/oldest one was the Florian Tower in Dortmund, Germany, built in 1959, now closed; and my favorite is the TV Tower in Berlin, built 1965-1969.

The primary difference

The primary difference between skills and powers is that the former cannot be altered by Modifiers or placed into Frameworks, which matters in ways that I’d prefer to discuss with very experienced users of the game. If one has a character without either of the latter, which is perfectly OK, then the distinction isn’t important. You can imagine a minor presentation of mine to place right here in the discussion concerning that issue in comics characters.

I have not changed the rules for skill concepts and range of use at all. The distinction between ordinary “I’m a professional computer guy” computer programming, for no point cost, and the comics/cinematic Computer Programming skill, which costs five points, is explicit in the first-generation text. The moment of play is precisely what would have occurred in the 1980s and nothing about Alpha or Beta is different from it.

One of my biggest priorites in re-introducing these texts to current role-playing is to highlight that the point-bought skills are absolutely not used to build ordinary people’s use of ordinary trained abilities.

The in-play window between having and not having the textual skill is, as I said, so narrow that I would not expect it to appear in play at all for most groups, and very rarely for the rest. I am considering closing it in the text, so that you simply do or do not, can or cannot do things based on the distinction between “ordinary use consistent with free concept” and “this is a comic book so I will try this nutso thing.” In that case, I would have ruled Mike’s action would simply have failed because he did not have the textual skill; or more likely, Alan would have narrated the action in somewhat less instant-amazing terms that involved more time/effort and less if any deception.

In the original texts, the default skill is 5 points for it to be equivalent to a characteristic roll e.g. [9 + (Intelligence divided by 5)], and 2 points per +1 that applies only for that skill. Various powers and more complex skills follow that model or differ by having a fixed default (11 or less) or setting the +1’s at a different rate.

In Beta, I have removed the per-skill and per-power currency rate for such things and shifted all individualized +1’s for skills and powers into the more generic Skill Level system, altered only slightly from the same system in the original rules.

Therefore in the old rules, you’d get, for example, Detective Work for 5 points and toss a few more points into it to make it better than the default Intelligence roll. In the Beta, you would buy Detective World for 5 points and then consult the Skill Level currency to do the same thing. It’s the same idea but I’ve centralized the relevant mechanic.

* I’d like to know more about

This question makes my head hurt. “Fiat” is the wrong word; it connotes an imbalance of power and necessarily means overriding current procedures or relationships. It has become part of role-playing vocabulary only because the hobby is already shot-through with confused procedures, social and creative power imbalances (not merely asymmetry), bad faith habits, and passive-aggressive emotional gamesmanship.

In all role-playing games, “things” have to happen or occur, and places have to be invoked for things to happen in, thus “where we are now” must be established. When these are done using understood procedures, no matter what they are, then the only possible term for this is “rule,” i.e., it’s how we do it (and not to be confused with what may be in the game text).

A lot of role-playing uses the rule of assigning this job, or most of it, to one person. In practice, it’s usually modulated by interactions with the other players, but that assignment is pretty easy to understand and to observe. That’s not fiat. It’s how it’s done, much as if, for instance, the job of saying what a given character says and does were assigned to a single person during play. Which is also very common.

Without qualification: any procedure of authority (establishing information and occurrence as “happening” or “happened”) which is known and used evidently as a known thing, is not fiat, it is a rule.

To answer your question more specifically, I enjoy determining when certain intrusive things occur through rolls, but it’s also functional to play them as Bangs (Sorcerer talk), today more frequently called Hard Moves (Apocalypse World talk). These terms refer to long-standing practices and both terms attempt to restore the older, uncompromising features of the technique from what has become a rather flaccid version. Such practices are not only common but necessary in playing any of the 80s superhero games.

I also used more player input than you may have realized by asking Alan very carefully whether he was meeting the investors or not.

It may be interesting, but I don’t think it’s very interesting. This is a constant feature of fiction, when characters with an in-fiction reputation or relevant past history are first introduced. Go to any prose fiction, theater, or film in which the character’s identity is not merely an invocation of known signals. What happens in front of your eyes bears little resemblance to reality.

In role-playing, all you need to do is remember that everyone is audience too, and think about how audiences are given information about such characters – and also remember that everyone is a creator and the local rules for the four authorities are in play to organize that.

Also, what you’re talking about may not be precisely as you perceive, in thinking about it as one-way GM-to-player. The Dark Cohort and “the villains from my past” were first brought into play by Mike and Frank respectively, by putting them on their character sheets as Hunteds. In other words, the first step or version of the process you observe is occurring toward me, not toward them. They are introducing supervillains to me (into “my” game) that I do not know.

None of us know that. It would be subject both to Frank and to me, but which of us carries the rubber-stamp authority over it is hard to say. It’s too easy to say “80s style GMing, so that would be me,” because you can see in the videos that I usually ask permission even to make suggestions about such things, let alone lay it down as a given.

Whatever we came up with, or however it was agreed or decreed to be the case, would necessarily have to take into account that Frank did not speak up during or after play to suggest that such knowledge might factor into the situation. That doesn’t settle the matter immediately, but as I say, it would have to be taken into account.

Rod: I only wish I had known!

Rod: I only wish I had known! Haha. Though of course Brian can't be impressed by any of that, since he's so used to flying. I bet he's big into subways and stuff like that.

Ron: Sorry for making your head hurt! I want to play the foreigner card here and say the word "fiat" will always be first and foremost a car brand for me. I know it just from that expression, "GM fiat". I'm not that innocent, I know it's supposed to be a bad thing, but I didn't realize it carried that much baggage. I'll be more careful in the future. Moving on: Thanks a lot! It's all really clear and helpful.

Restaurant conversation

* I'd like to know more about the pacing of having the restaurant conversation be interrupted, at that point, by the appeareance of the villains. Is this just GM fiat? Was there a roll involved in making them appear before the other guests showed up? (Other guests= the investors or whatever that were going to sit down with Mike, his brother and his wife.)*

I think there was a lot of unspoken cooperation going on in the lead up and resolution of this section of play. Certainly, I tacitly cooperated with Ron when he suggested Aaron wanted to meet for dinner. I could have had Mike dive into old records in the PowerCave or something. But I was committed to the paradigm of alternating between super and personal events that I've been reading in old comics. I wanted to explore some melodrama. Ron also set the location as the Space Needle, which I could have spoken up about, but again felt appropriate to my conception and expectations.

The scene in the restaurant played out in an utterly classic fashion: Aaron and Michelle bring out their concerns and turn up the pressure. Mike took a hard stance that means somebody has to back down or get angry. Then we were interupted by a superfight that sidetracks the issue only to have Aaron express affectionate relief that Mike is okay at the end, temporarily relieving the strain on their relationship. It produced a very satisfying result.

As I see it, Ron did two significant things. First, he picked up on my decision that Mike was drawing a hard line and identified that as good time to drop a classic superhero distraction. Second, he thought to have Aaron reconcile with Mike at the end. I'm not sure those things are codified in rules. I think they arise from the natural human sense of rising and falling tension and experience knowing when to call a scene done.

Incidentally, on reflection, I could have had Mike be more clever and just go along, but I think I was looking for a point of conflict and I had already grasped Mike's issues around his secret ID as the sticking point.

How would it have played out if Mike had met with the investors? I think the villains would have shown up at some point.

Thanks Alan! I gotta say, I

Thanks Alan! I gotta say, I really enjoyed those scenes with the family. I have just finished Part II and will be moving on to the next session, which Ron has recently posted. Having finished both parts of this session, I want to compliment you on you resourcefulness as a player: I was delighted to see you a) pretend to work at that restaurant, b) teleport so it makes a flash and messes up with the eyes, c) using that Entangle on the 'battery', for me the most surprising one. I really thought your guy would not be able to do anything against these people. I'm going back at the former posts to take another look at your character sheets!

Thanks for the compliment

Thanks for the compliment Santiago! You're talking about the battle with Eyefire and Obsidion around the Space Needle, right? I think the use of Entangle to reinforce the broken spar of the Space Needle is a good example of applying the Special Effects rule. My entangle was defined as a field that immobilizes matter in space-time, and I had it bought at one hex area effect, so it makes sense that it could prevent structural collapse. If it had been simple a net, for example, it might not have applied. PowerStar is designed with flash and entangle to make opponents easier to hit, then he teleports in and punches them with martial arts.

Thanks for clarifying! I

Thanks for clarifying! I looked at the sheets and, yup, the flash is there. What I hadn't realized is that your use of Entangle had been a case of applying special effects.

Thematically, is it like…? Like, PowerStar is just reversing whatever allows him to move/teleport matter through space, making it pinned down instead?

Having finished watching both

Having finished watching both parts of this session, but without starting the next one, I have another question related to pacing/scene framing. This actually goes back to something I struggled with in both the Tales of Entropy and the Champions The Defiants games. It's about what you think about doing between sessions. In this case, Ron ends the session saying "There's an energy source here, and you two are the only ones that know about it". As a player, how does one go about communicating what one wants to do with it? Because it's the end of the session, you can't say "I put a security system around it" or whatever. But I feel the following session may start by "You find yourself talking about such and such with an NPC", leaving that hanging.

For all I know, the next video starts by discussing just that, but I wanted to pose the question before I concentrate on watching it and just forget. It's something I'd like to have more clear for when I play Champions as a player, not GM, and similar games. (Entropy is not at all similar and I don't mean to encompass it by this question, I just mentioned it out of personal history.)

At the beginning of the next

At the beginning of the next session, Ron didn't put us directly into a scene. He did describe Federal agency showing up to take control, so I think that's why we didn't worry about protecting the Needle. Then he asked us, the players what we wanted to see in the coming session. Then we went into a scene. As it happened, both Frank and I felt it made sense to consult with Dr Darkstar about the Space Needle battery, so that's what we did next.

You’re right! When I started

You're right! When I started to watch the video, I realized it wasn't an issue. Though, still…What if you or Vince's player had been more paranoid, wanted to declare your characters refusing to let anyone access the energies. Do you, like, simply interrupt Ron and go "Wait, when those feds arrive, I'm right there, studying the energies."

Come to think of it, it seems simple enough. I think I'm getting it. But do tell.

Santiago, I’m not sure if you

Santiago, I'm not sure if you're asking about whether it's okay for players to speak up and say "Hey, my guy wants to do this instead!" Or are you asking about how a GM responds when a player does that?

For the first — I had no doubt that I could have declared Mike was doing something different and Ron would have run with that. For the second, I could give my GM approach, but I think I will invite Ron to respond. Ron?

It was the first! Yeah, it’s

It was the first! Yeah, it's probably so obvious to you as to be simply "saying what my guy does". But I had to go through the process of saying it out loud, with someone on the other side, to get it. Thanks for your patience and the information.

(Just so you don't think I'm an alien, let me explain that at the moment of asking I was acting as if Ron's words were set in stone the moment he pronounced them, and I didn't realize I was doing that. So I was all "Oh my, oh my, how can I tell him my guy's there when the feds show up if he's already saying they showed up and set camp without me there". It really does seem obvious, now, that you just go "Nah, Ron, I'm already there".)

I don’t have much to add to

I don't have much to add to what Alan has said. The only thing I can think of is this: "session" doesn't mean very much in Champions, as a unit of narrative. You aren't done with anything in fictional terms just because the real-world group happened to stop playing. Instead, and conveniently, it's quite analogous to an "issue" of the comics titles as they used to be published through newsstand distribution, during the period that most inspired the game's authors.

The numbered issues of a comics title from that time were fully separate in time and as objects, but the fictional relationship from one to the next was very flexible. It could be completely continous, literally simply moving from the panel of the previous issue to the first panel of this one with a panel of repetition as a reminder; it could be completely discontinuous, as if you were beginning a whole new book in an ongoing series of novels; or it could be anything in between. The same range of transition might be found within the pages of a single issue as well.

To some extent this parallel is true of practically all role-playing games published during the 1970s and 1980s, but even more so for Champions, because the text and much common practice encouraged naming and numbering sessions of play as if they were issues of a titled comic. When I call our recent games "The Defiants" and "Legacy," it's not informal, as it would have been for equivalents in playing RuneQuest or D&D or Traveller.

To turn this into role-playing practice, I'm saying that session transition for play is nothing more nor less than scene transition, including the far-end case of not any sort of fictional transition at all.

If I may speak here as someone who's been playing with you steadily for about a year at this point, you really struggle with how such transitions occur in play, and also, similarly, with what to do when your character is not immediately in danger. It may be that your struggle is so intense because role-playing differs profoundly from improv comedy: it does not include a mandate simply to seize upon the first available signal for "where we are and what to do" and to adhere to it. Again, at the risk of being offensive, and based on my entirely unasked-for judgment, at these points of play, you consistently enter into a state of creative panic.

I don't want to get into a debate about this, since it's a personal judgment, and if I'm wrong, then I'm just wrong and will accept that. But if I'm even a little bit right, please consider that no role-playing game will ever solve this problem insofar as it's a problem. The most it can do is provide either more or less specific steps to commit to, without "solving" the problem as the rules of a board game might.

Furthermore, in many cases, less formalization of these points of play may be better than more. Looking at my own designs, I can see that I provide much more clarity about transitions in location and time than most RPGs do, but play widely across the possible range for character actions at those points, i.e., whether a given design requires saying "this is over, stop," and "this is beginning, start," for player input. My design range includes the far-edge case of including no such statements, requiring/accepting considerable freedom and local customizing per moment of play.

Ron, thanks a lot! I’ll

Ron, thanks a lot! I'll answer in order: first, it's really enlightening to read that the names you use for Champions games are actual titles, not just nicknames like in the other posts. Session transitions being scene transitions made a lot of sense as well.

No debate; I’m actually relieved! I also feel I really struggle with that, and it’s nice to see it confirmed. I was doubting my self diagnose and wondering if I was just being difficult. It’s also relieving to read no game, no rules configuration fixes the problem, because it means I can stop worrying about it from that angle.

It may very well come from improv comedy, who knows. I’ve never actually done it, though I did take four classes a few years ago. But it’s all around me, culturally. I do stand up, and there’s both a rivalry and an exchange of practitioners between the two fields, in my city. A few years ago I used to go watch improv comedy every Friday, for almost a full year or two. And I’ve been paying it a lot of attention since I got back to studying roleplaying via your blogs. Plus it’s also something that really interested me as someone who writes and teaches writing, which to me, as you've also already pointed out, means always thinking about how do people come up with things. (And of course my clown sister -who Ron, Rod & Ross have already met, guys- has done improv.)

I can subjectively say I felt panic (well, “panic”) when I thought what would I do, were I Alan and Frank at the end of the session. The qualifier “creative” wasn’t part of my subjective experience, but that may very well be it! I just experienced it as paranoia of the sorts of, “I want to control that variable, who knows how I’d deal with it, later on, if it turns out to be a problem”, meaning, what if the feds turn out to be villains and use the battery against my character. How will I know how to deal with that? — Ohhh, there’s the creative panic, now I see it. Spelling things out loud is turning out to be really helpful for me!

You know what? This is the first time I’ve considered “Yes and” doesn’t apply to roleplaying.

I want to revisit one concept

I want to revisit one concept because your paraphrase is not accurate:

That isn't what I said at all. I said that session transitions were analogous to the transitions between monthly issues of a newsstand comic. That means they are fully open to the entire possible range of fictional associations.

To be absolutely sure I'm saying this fully: insofar as we're talking about role-playing as an activity, session transitions are not mandated to correspond to any fictional transition or "fade" or special activation/inactivation of play. Such mandates may be in place for a given game's rules, often for good reasons, but they are not intrinsic to the activity.

Upon re-reading, I figured

Upon re-reading, I figured out the problem: the following bit I wrote is wrong.

Replace it with what I wrote in the new comment.

Hahaha I had already grabbed

Hahaha I had already grabbed that paragraph and had it on clipboard, to paste here, before I had finished reading what you wrote.

But I think I get it. You're still saying it's not a "major cut", MORE than a scene transition. You're clarifying it doesn't EVEN have to be a scene transition; it can be LESS. So we could wrap up playing for the day in the middle of a scene, and continue another day by resuming that scene. Right?

Hi Santiago, I’m curious

Hi Santiago, I'm curious whether your sense of the finality of GM authority came from experience or whether it was just your uncertainty playing with Ron? You're in Spain, right? I wonder if there are regional differences in how the authority in roleplaying games is handled.

Alan, thanks for asking! It’s

Alan, thanks for asking! It’s an open question, really. See my latest exchange with Ron where we consider my familiarity with improv comedy.

I’m in Argentina, actually. Which in this case means I don’t get to tap into Spain’s rich tradition of geek culture, which goes back at least a few decades. Instead, in Argentina it’s all more recent and/or sparse.

You can actually read my complete roleplaying history right here on this site, by clicking on my name or the Argentina tag. It’s not much – I mean, it IS a lot to read, don’t do it if you’re not super curious – but I mean it was just around ten or fifteen sessions in total, in the span of two decades, before I started playing with Ron. What I did do, in that span which for me is between the ages of ten and thirty, is read everything I could get my hands on related to roleplaying. Perhaps that was enough to absorb a lot of bad habits of roleplaying culture – though, at the same time, a big chunk of my readings were Ron’s writings, Vincent Baker’s, and the Forge forums, so believe me I’m the first one to be surprised when I treat the GM as a god.

Then again, to do another little twist, I’ve also read a lot of, say, “traditional” game design, interactive fiction, Hollywood scriptwriting theories. Greg Costikyan, Emily Short, Syd Field, Doc Comparato, Robert McKee, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, Roger Ebert, anna anthropy, Film Crit Hulk, Raph Koster, Chris Crawford. So now that I’m actually playing regularly (my first multi session game ever was Tales of Entropy, right here on this site), I’m really learning the distinction between multilinear, choose-a-path interactive reading, and in-the-now, fiction co-authoring.

Hi Santiago,

Hi Santiago,

From what I know of improv and performance I can understand why you'd be inclined to take another player's (I include the "GM" as a player) statements written in stone. In improv or performance, the rule is to respond to what is given without hesitation. That's the improv process of accepting something as "real" in the fiction. As you've probably learned from all your reading, this process is often not fully documented in any give text for a roleplaying game! That has been a source of much discussion and definition in the past.

In practice most tabletop roleplaying allow room for discussion: offering suggestions, asking for suggestions, and negotiation — before a final decision — so you are not "on the spot" in any given moment of decision.

Thanks a lot, Alan! 🙂 It

Thanks a lot, Alan! 🙂 It really helps.