We are continuing to play Proteus, as first described in Magic, mutants, rats, guns. As you may recall, after the flashback session, we are back in the present as Ramzi the newly-arrived Stygian, Rhena the Rhat, and Siobhan the mutant escort/eros-priestling are battling stinking dead dogs apparently determined to kill Master Gah, Rhena’s mentor in the arts of enchantment. It ended in a very messy smear of various fluids. As you will see, we, especially myself, are still in the learning curve for plenty of basics.

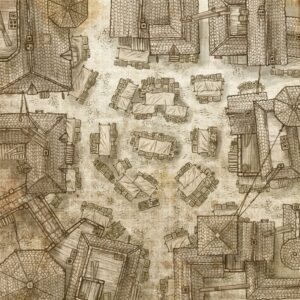

I repurposed this map from the current AD&D game as it is a very fine “market stalls” venue for fights or whatever else; we put Master Gah’s hovel/shop at the top center and treated the top border as the cliff wall.

The fight ran pretty much along that walkway (“street”) in front of it, left to right, and the stalls across the way were upset and trampled by one of the zombie dogs. Ramzi took his stand in the alley to the right of the shop, and the mysterious fellow fled “down” from there past the surviving stalls.

Now I want to talk about the d30. Some of the rolls are merely to be equal to or under your skill number (1-30), so it’s merely % in constant 3.33% increments, exactly the same as any single-die target roll, differing only in the increments’ magnitude.

A lot of the rolls are instead opposed: both sides roll and check vs. their respective skill. It’s important that you don’t really consider “success” for the opposed method, in this game. The arithmetic procedure is that each person subtracts their roll from their skill value, then we see whose result is more negative to see who’s screwed. Therefore, unlike RuneQuest attack/parry, it doesn’t matter whether you hit your skill value or under, because even if you technically fail, you’ll still get the other guy if they suck worse than you did. And the skill value still plays a big roll, for the following reasons.

A good way to look at it is that it’s really a 2d roll, and although we’re assessing whether a given side rolls better, it’s still just a bell peaked and centered on a difference of 0. To review, that means the center values may be arrived at by many available values on the dice. The more extreme values (toward min -29, or max 29) may only occur with fewer possible outcomes; those are the flattish parts at either end.

The above paragraph’s numbers assume that the skills involved have the same rating so you might as well be using the naked rolled results. But if they don’t, and keeping one side stable as “our guy,” the effect is to skew the top of the curve to the right (higher than 0) when their skill is better than the foe, or to the left (lower than 0) when it’s worse. For instance, if one person is using a skill at 28 and the other is using a skill at 2, then the graph for the first one’s success is centered at 26. (Many analyses of these curves are interested in the height of the middle part, but that’s not an issue here.)

Anyway, this graph and the concept are totally the same no matter what size die you use, as long as each is a single die and they’re the same size. The only difference is the % increment shifted. Therefore there is nothing exotic about using a d30; it is not a “special die.”

The real design consideration is how gaining and losing skill increments affects the result, and for what part of the range. We could be talking about momentary bonuses and penalties, or about permanent changes, most often associated with improvement (“advancement”).

Briefly: since the graphs shift right or left without internal modification, bonuses or penalties count the same no matter how good or bad you are with the skill. Any plus or minus shifts it exactly that many units (of difference) over.

It strikes me now that instead of the dogs’ being disadvantaged due to their inability to dodge (being dead), they were actually better off than if they had a bad skill to dodge, e.g., Dodge 1. Maybe I misplayed it! Because in that case, the difference between their 1 and Ramzi’s Pistol 14 would have shifted his curve way over, because all he had to do was “miss less,” e.g., he could roll a 29 (the worst possible without fumbling, for a total of -15) and still hit the dog 50% of the time, and if he rolls his skill value, 14 or less, it hits no matter what the dog rolls. Whereas as we played it, he only hit if he rolled 14 or less.

And in this case, the real concern is how much damage is being done, because a lower roll, i.e., a bigger difference between your skill value and the rolled value, is adjusted by a weapon’s damage factor to determine the hits delivered to a body location. As it stood, Ramzi’s potential difference on a hit ranged from 1 to 13, and that’s it; as I’m considering now, it would range from 1 to 40. [These numbers are complicated slightly by the critical/fumble rules; I’m ignoring those outcomes for simplicity right now.]

That would explain a lot about why his pistol didn’t produce the feared/awesome results that one might expect given the setting and cultural concerns over gunpowder weapons. I feel bad for Johan because he played Ramzi very nicely and accorded completely with the rules for timing, but didn’t see the presence in play one might reasonably expect. I’m not talking about failure as such, which can happen to anyone, any time, but rather the effects of a success.

So I’ll review the rules, because I think I didn’t understand this feature well enough during our sessions so far. I haven’t yet found a section on unskilled attempts to do things like dodging, which is probably the right concept to pursue.

Also, yet again, I add to my notes for bad situational GMing: I completely forgot that one of the outcomes during the flashback sequence was that Rhena gained a trinket of reward from people who are, after all, superior enchanters, and who had some inkling of what she might be up against. So instead of a Luck-based rummage through Master Gah’s stores, she should have had a perfectly good thing to use already.

One response to “Smelly scuffle”

SESSION 4

Here’s the direct link to the video inside the playlist.

For those who may wonder, the cap Figo is wearing is the traditional gymnasium graduation cap in Sweden; all the graduating students wear them throughout the week and it’s a city-wide occasion of parties and congratulations.

Regarding the session, you can see from these notes, taken just after session 3, that I had a very good grasp on the situational circumstances and would be in good shape to finish preparation and play … usually. During the next three weeks, two sessions of EABA, two or three of Advanced DnD, and both Advanced D&D and Circle of Hands at Lincon pretty much ate my brain, and all I had come up with by the time of play looked like this. Actually, that’s not quite fair; I had worked up Uleck, the Overlords’ agent, into a complete sheet, which mattered a lot.

The session’s first half is deceptive. It looks slow and shy on play … but in fact, the group is engaging entirely with the setting and aspects of the system. Johan in particular puts together some pieces about his character, and everyone becomes fully energized about what’s going on and what to do, me included. It was easy to play from there, not too long, but thoroughly on and committed to the procedures and content.

I had purchased actual d30s at Lincon and was happy to use them, but Helma insisted on retaining the d6xd10 method, reminding me of how I felt when dice marked 1-20 were first made widely available. It seemed wrong not to be using d6xd20 (the latter marked 0-9 twice).

I didn’t mention during the video that after the zombie dog fight, Ramzi would be wearing both his pistols rather than just one. That’s why he was able to run down and shoot again right away.

Figo is moving out of town so we are probably not going to continue, but we are all sad about this. The game system really came together for us, and I now appreciate the clarity of the opposed rolling system and of the magic resources. Everyone is now interested in consequences from the built-in tensions in the textual setting, amused or intrigued by several NPCs’ points of view, and oriented about “where to go” with developing their characters, i.e., which pieces were strengths and which led to conflicts or uncertainties.

As has been the case for every fantasy heartbreaker I’ve played, I’ve learned a great deal. For example, in this case, the curious ordering procedure looks over-calculated and decidedly un-clever, but it resulted in rapid-fire, decision-heavy, exciting choreography. Critically, failed rolls turned into immediate circumstances rather than speed-bumps or wondering why one bothered. Similarly, the attributes seem overly complex and full of derived math regarding rolls and points, but as it turned out, the nuances of Memory and Luck played perfectly into the more prosaic activities based on Agility or Cognition (perception), and even the careful distinctions among Stamina and Mass turned out to make a serious difference regarding what happened. I am gaining a lot by comparing it with the superficially but functionally very different attributes in Legendary Lives.