Inspired by a discussion as part of Ron’s current People and Play course, here are some of my thoughts about when and if to use resolution systems, specifically the dangers of going there too early.

I’ve run Gunther must die, the introductory adventure for my game In the Realm of the Nibelungs, three times now. Twice, it ended up in a very similar and dire situation, with very different outcomes.

(SPOILER ALERT)

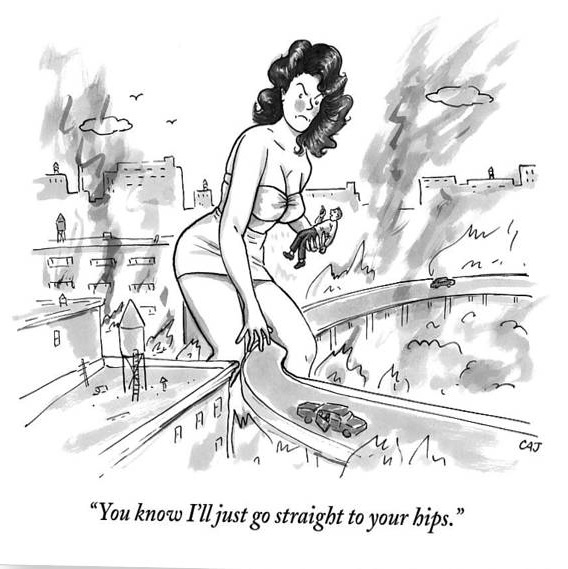

The heroes were tasked with saving their king. The king had insulted the beauty of Lodinga, a giantess. She had then kidnapped him, vowing to devour his manhood within seven days.

The two groups both ended up noisily killing Lodinga’s guard dogs and being cornered by the angry giantess.

*-*-*

In group 3, Dwayne, playing a bard, had him step forward and address the approaching giantess: “We are raelly sorry for killing your dogs. Can we make amends?” I said, somewhat apologetically, that I did not see how that could appease her and that she would attack, very likely killing everyone. We then engaged the combat system.

Lodinga knocked out one PC (lucky him), killed another (Dwayne’s, as chance would have it) and then got killed by a very lucky crit (three 6s in a row). The players were relieved, but also quite frustrated. Dwayne noted that he had expected to be more effective in his appeal, being a bard.

*-*-*

In group 2, Larry, also playing a bard, stepped forward and addressed the approaching giantess (after she had already killed two PCs): “Hear me out! If you kill us all and then our king, you will forever be known as ugly in all legends because monsters that kill kings are always portrayed as ugly, whether true or not. Let me show you a way to avert this unjust fate!” I had the giantess stop and listen. She was conflicted, wanting to fullfil her oath but not wanting to go down in legend as ugly. Larry’s bard offered to stay at her side for seven years as her personal bard and spiritual advisor (read: public relations guy and therapist), helping her deal with breaking her oath and discover her inner beauty and self-worth. I decreed a Charisma roll, an easy task for a bard: Success, and she accepts. Failure, and she will – unhappily – kill you.

Larry’s roll succeeded and the other surviving PCs left with the king. The players were ecstatic.

*-*-*

(I should note that a direct confrontation with Lodinga, whether over her dead guard dogs or not, is not pre-ordained by the adventure’s set-up. There are multiple other options, as shown by group 1, discussed here.)

*-*-*

I think Dwayne may have been focussed on engaging with a specific part of the resolution system (a Charisma check) rather than focused on (or be sufficiently inspired for) making a compelling fictional argument (which would then either trigger a Charisma check or simply resolve the situation with no roll).

To be fair, Dwayne painfully felt at a loss for something clever to say, but stepped forward because that seemed like the best last chance to avert everyone being slaughtered. He was also wowed by Larry’s approach when we discussed that later.

(It sure helped Larry’s ideas were from actual play, rather than I, the GM, spitballing how the situation might have been solved.)

9 responses to “Two executions, one averted”

I just noticed that both executions were in fact averted and the final outcomes were in many ways the same (some PCs survive, the king is saved). How we arrived there, however, feels totally different to me. It has been a joy to run my adventure multiple times and experience this.

Dwayne’s failure is refreshing. I can think of many similar situations in which I was GM, and engaged a roll “because at least the player was trying”. Looking back I see that behavior as flat-out patronizing.

Dwayne didn’t come up with something good enough, and that’s that. Clearly this is no sin on his part; it’s just how the game is played.

I’m *so* guilty of granting rolls just for trying (or wanting something hard enough). But you’re right: that’s actually patronizing! I’m slowly growing more confident (as in the above instance) and such realizations help.

Your wording was much better: engage, not grant.

I need to get past a couple of things in order to say something constructive. One of them is specific to Larry’s content, and the other concerns “the bard” in general … and neither is any of my business nor has anything to do with your topic.

Past my issues and to the point, the question really comes down to whether a roll is triggered by the stated activity – what I call shifting into outome authorities. I even have some arrow-type diagrams in which arrow #1 culminates in the shared knowledge that “now we must shift to outcome-based play,” in this case specific sorts of talking which include a roll.

The related concept is I I E E, or intent initiation execution effect, strictly as fictional content. Therefore “intent” isn’t what you as a person want to happen or even what the character would like to happen eventually, but the fact that the character is committed to act. These terms may be procedurally combined or separated in any imaginable way, and they may be distributed in many different ways across the arrows.

Work with me a little bit:

For some games and/or groups, a roll is warranted if a bard opens his mouth. We might want to know the basic goal or a bit about what he says, but it’s not that important; instead, we’ll see how the roll goes, then the player or some excitable participant will tell us what it was. The roll basically determines the quality of what he says, so we have to see it in order to provide corresponding quality or lack thereof. In my notation, it’s [I]+[IEE], and for the arrows, that means the first bracket must be locked down in the shaft of arrow #2, and the second is attended to in the entirety of arrow #3.

For others, a roll is warranted after we know what the bard says in some detail, with its goal absolutely clear. The roll therefore does not determine what he says but more about how it lands, or even the emotional receptivity of the listener. In my notation, it’s [I]+[IE]+[E], and for the arrows, the first bracket is the arrowhead of arrow #1, the second is the entirety of arrow #2, and the third is the arrowhead of arrow #3.

In your case, and evidently as you see the proper play of this game, it’s absolutely clear that the second description Is How We Do It. This is fine (if you don’t mind me saying) … but my point is that leaving these these descriptions unconstructed results in painfully incompatible expected procedures at the table. One may play it safe and say “[this way]” is in fact exactly how we do it, for maximum clarity. Whereas some games do very well with a point in the arrows at which the method is customized to the moment.

For anyone who’s interested, these terms and concepts are addressed with learning activities in my courses Action in Your Action, Phenomena, and Playing with The Pool.

Let’s see if I understand what’s been going on:

Arrow 1: A player says “I’ll do X.” and – in this case – is also expected to give concrete details (i.e. not just “I’ll talk to the giantess” or even “to make her let us go” but the actual argument he makes). With the player now committed, we need to know whether the outcome is uncertain.

I have the (unstated) authority to judge whether there is uncertainty in this case and whether we even need to have a roll.

(I would not have this in case somebody intended to shoot an arrow at her, i.e. I can’t normally say “There’s no way you’d hit.”. Instead, I’d be expected to go to the combat system with Armor Class etc.)

With Dwayne, I decided that the outcome was not in doubt. Lodinga has the capacity and confidence for extreme violence – a default for ‘D&D’, i.e. nothing I consciously considered as I might in a different setting – and the PCs have trespassed and killed her dogs. She’ll attack.

With Larry, I decided that the outcome is in doubt because the argument specifically leverages a fictional constraint: Lodinga has been established as caring about how her physical appearance is perceived. Hence, an appeal to her vanity (or triggering her fear of being seen as ugly) *might* succeed. This decision (i.e. “There is uncertainty here.”) is mine and constitutes arrow 2. We move on to Arrow 3 and roll.

*-*-*

Other games (or groups) might handle this differently, e.g. a character (or maybe just a bard with particular powers) might always be entitled to a roll–in which case the player would not have to give concrete details yet. After all, we’ll roll anyway and the procedure is likely more about interpreting the roll.

In my example, there is some leeway for deciding which of the two approaches discussed should apply–because the effects of “talking” are notoriously (or perhaps fortunately) undefined in many games directly descending from ‘D&D’.

(This lack of definition regarding a particular type of situation is probably best adressed beforehand in the case at hand, but it’s interesting to me that this may not be true for all games.)

I’m thinking it’s probably OK with you for me to get a little instructive about my diagram … so, that arrow #1 culminates in the recognition of uncertainty that must be acted upon, however we do it in this game. You can look at its first “shaft” part being plain old situational/scene play, and the arrowhead as saying, righty then, it’s time to shift procedures. So most of what you’re talking about is in this arrow, and why/when you recognize that we are in the arrowhead.

Once we’re talking about fictional cues for that recognition, then we can look at the configuration of IIEE (which is totally and only fictional content) which constitutes the recognition in this game/group. You’re definitely tagging at least Intent & Initiation for that job, meaning the character has genuinely begun to speak and to introduce their topic (“where I’m going with this”), possibly even a bit of Execution (“my point being …”). As you’re describing it, we are not even into the arrowhead of arrow #1 until that content is understood by everyone present and evaluated by those who tap the arrowhead and say “Now we’re here.”

Let me know if that makes any sense or is at least interesting. It’s definitely a primary subset of the “Nuts and Bolts” third session of People and Play, as one of those things I promised would be in further courses.

A couple of notes: first, you’re absolutely right that this family or presumed family of design leaves this element of play pretty unstructured. I think this was a positive feature in the pre-mid-80s versions, because there was no attribute check or skill check aside from very designated class abilities, in turn because … one didn’t check those things at all, in the dice sense. The situational authorities were deemed sufficient and, in my view, in AD&D especially, plenty of content was present and sufficient to do so, mostly unconstrained except in plain old fictional terms, some formally constrained, including Reaction rolls. A skill system was introduced during the mid-80s and especially with Advanced D&D 2nd edition in 1989, which is in fact a totally different design with D&D coloring airbrushed onto it, and talking to NPCs has been a hash ever since, unfortunately repeated in the next total reboot in 2000.

Second, if we’re talking about design in the context of your consulting relationship with me, that post-1989 hash is no prize or desirable feature at all. Good design requires a real relationship between IIEE and the arrows, either strictly or designating its included wiggle-adjustment points, but always “like this.” Failure to do is is guaranteed murk and the consequent imposition of the death of play, control.

Third, if you can stand any more of this arrow talk and are interested, then the second arrow’s shaft holds all the pre-roll preparation and orientation, which might be checking various target numbers and modifiers of the moment, or clarifying exactly where everyone is or any other fictional circumstances that will be good to know now, rather than being disruptively confusing once we see the roll and have to do something with it. The roll itself is arrow #2’s arrowhead. Arrow #3 in its entirety is after the roll, and its arrowhead is the definitive impact of what happened (in your case the end of Execution and the entirety of Effect); then arrow #4 is returning to situational play. [I keep saying “the roll” as if it’s a single thing for simplicity’s sake, but obviously, I hope, it may in fact be multiple rounds with multiple actions, with mini-versions of arrows #2 and #3 as subunits.]

I appreciate your patience, as I still have a lot to learn.

In Arrow #1, when I decide that there will be no roll (in Dwayne’s case), I’m in the arrow’s shaft, exercising my situational authority (in this case, determining what NPCs and monsters do, though you point out that ‘D&D’ offers a possible procedure for this: reaction rolls) and ‘extending’ the shaft: There’s no arrowhead, ‘regular’ play goes on.

When I find I’m not sure (in Larry’s case), I tap/create the arrowhead, admitting I am uncertain. Because it’s my job to decide these matters (i.e. I have authority over the monsters’ reactions), we need an outcome (rather than turn to another authority). Everyone realizes we’re activating some procedure.

In Arrow #2 we sort out the procedure: which one (e.g. a Charisma check), what we need (e.g. the Charisma score), possibly what is even covered etc.

(For instance, I noted that there would be no further Charisma checks for other arguments, *at least* until Lodinga had executed a full round of attack(s). As a recovering illusionist, I often foreclose the possibility of the GM granting (or the players begging for) *another* chance. This sort of nailing down a range of possible outcomes carries its own dangers, but that’s another topic.)

Arrowhead #2 contains the dice rolls and – I’m not sure about this – subtracting hit points etc., as parts of “carrying out the procedures”.

In Arrow #3, we make sense of the results, i.e. translate things back into the fiction: You are reduced to 10% of your hit points in one blow? That must have been a brutal blow. We interpret and narrate according to our authorities and settling things constitutes Arrowhead #3.

(For Arrow #3, I’m not quite sure of the shaft vs. the arrowhead.)

(So “That’s three levels of success.” is still Arrowhead #2, exclaiming “You’ve wrapped her around your little finger!” is Arrowshaft #3 and narrating the details (“She’s falling in love with you” vs. “She can’t help but be impressed by your reasoning” is Arrowhead #3.)

This is slow going, I’m afraid. And I have only just realized that IIEE may map onto the arrows in different ways, but we can leave that for another time.

Arrowhead #2 is just the roll. Arrow #3 is about applying the results, e.g., comparing it to Armor Class, finding the damage, seeing what the damage does to hit points – any and all processing. Arrowhead #3 is the resulting understanding and finalization of its effect, including statements like, “He’s dead,” “That must have been a heavy blow,” or “She’s wrapped around your little finger,” or whatever. It may or may not include other consequences and descriptions depending on the game and group.

But you’re right to recognize that IIEE is organized and distributed very differently for different games, and often differently by group for the same game title. As I mentioned above, procedures may get us well past the roll before we’re required to describe the events that led to the effect … and if at first glance this seems weird to you, considering how often the real-people interaction is quite prosaic and non-descriptive until we see the roll’s outcome: “I hit him,” roll dice, “Success!” more dice “Ten points!” [on d10], and then someone describes how the opponent had overreached or otherwise been careless, and that the character had nailed him through the heart with a sudden stop-thrust or something. In other words, only Intent had been in place until the moment of the roll established Initiation with no description at all, so only after we processed everything and were all the way into arrowhead #3 did we complete Initiation and apply Execution and Effect.