Across three sessions: a bank robbery, a public unmasking, our protagonists finally have their show down, and a guest appearance by the most startling character of them all! Plus—the second death of the First Responder!

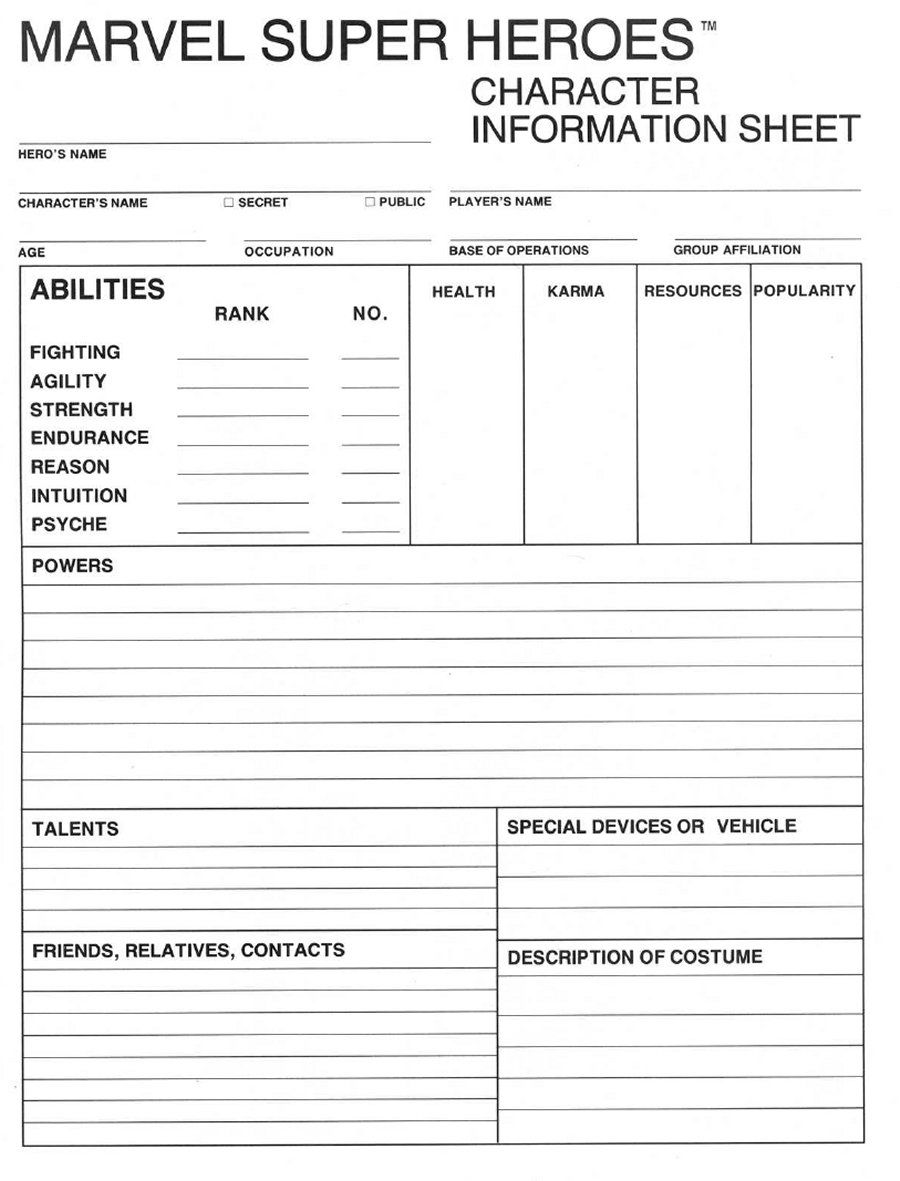

James, whatever happened with that Marvel Super Heroes game David was running for you and Noah? There were a lot of session summaries and I kind of skimmed them.

Connie (played by Noah) is a terminally ill supervillain with a high tech suit that gives her ghost powers. Sam (played by me) is a down on his luck eco-terrorist who dabbles in magic. When Connie realizes science can’t cure her condition, she tries to get help from Sam. Not realizing that Sam has been trapped in another dimension, Connie thinks he’s simply ignoring her. She kills his pet, steals his grimoires, and threatens his ex-wife. When Sam finally returns to Earth, he’s now locked into a cycle of vengeance against Connie. She’s the smartest human being on the planet and simply better than him at everything. It’s human versus superhuman, no holds barred!

Now I remember. And at this point Sam has run out of Karma, a resource that would even the odds a little, right? Seems like the best move would be to knock over the chessboard.

Yeah. Turns out that trip to the other dimension was pretty useful: it gave Sam blackmail material to use against his parole officer, a guy with telepathic powers aching to send Sam back to jail for the slightest violation of parole. By comic book coincidence, the parole officer is a refugee from that dimension. By threatening to send the guy home, Sam clears up his past indiscretions.

Yet so long as the Law is constantly peering over his shoulder, Sam can’t get down to the real business of saving the earth by any means necessary. Since Connie, in addition to threatening Sam’s family, is also on the run for murder, Sam proposes to bring her in, in exchange for being released entirely from all supervision. The parole officer agrees.

Sam grimaces, not liking what comes next: “All right, damn it. You’ve got yourself a superhero.”

Wait, “superhero”? Wasn’t the point to play villains? I know this game allows a player to switch sides, but I’ve never seen it play.

It’s literally the first time I’ve seen it done in 40 years. But procedurally it’s simple. You say, “I’m a hero (or a villain) now,” and lose half your Karma. Then you play by the similar-but-not-identical rules for heroes or villains. If, like Sam, you were already at zero Karma, there’s no downside if it makes sense for the character.

And for Sam, it did make sense. He’s a schemer but not a sociopath. Last session he murdered his heroic arch-foe, the First Responder (this was, I think, Sam’s first homicide) and it left him shaken. The first thing he did after getting back to earth and cell phone service was to call his mother to ask if he was a good person: “You’re not a bad person, Sam. You just… care too much.” I wasn’t expecting David to nail it that way, but it was 100% correct.

As lifelong Marvel Comics fan, this moment of moral instability felt absolutely gorgeous. The company has a handful of genuine anti-heroes: the earliest version of the Hulk, the Sub-Mariner, Quicksilver, Yellowjacket, the mid-60’s Black Widow. Even lovably wholesome characters like the Thing and Spider-Man were, for a few delicious early scenes, contemplated lives of heartless criminality. Accompanied by anti-villains too: Doctor Doom from the earliest days, but the Punisher and Magneto as time went on. I don’t know how to describe it—there’s electricity in every panel with these guys when they’re at their best/worst. It’s a particularly rich vein in this literary canon, and this game absolutely nails it.

Okay, so what’s Sam’s first deed as a superhero?

Well, he communicates with his family to make sure they’re safe for the moment, then arranges a showdown meeting with Connie. On the way, he donates most of his remaining money to charity—Karma boost! And he then calls a news station to reveal his secret identity and origin to the world—Popularity boost!

You can’t fight her straight on, so you’re making yourself luckier, more persuasive, and able to operate in the open.

Exactly! And after that… maybe a return to villainy? But as far as actually, like, fighting Connie, I did not have a plan. I’d just have to bump into her and hope for the best.

What about Connie? Was she just sitting still this whole time?

We kind of had a rhythm of Connie-heavy sessions alternating with Sam-heavy sessions. But in this instance she tracked Sam’s ex-wife to a resort in the Hudson River Valley, and was stalking her for a bit. But Sam’s ex was a little too cagey. In a nice bit of characterization, Noah remarked, “Connie’s frustrated. And when she’s frustrated, she makes things.”

In these rules, inventing stuff requires spending (lots and lots) of money. So Connie decides to knock over a bank, a robbery which also awards her villainous Karma. I don’t believe she kills anyone.

As she’s escaping with $150,000 in bearer bonds and jewelry, the moment of truth arrives. After playing cat and mouse with Sam for several sessions, Connie’s sociopathic scientist finally meets her match….

…The man-insect Bug-Morph.

BUG-MORPH?!

Bug-Morph. He’s one of a few NPCs David’s referred to every few sessions—some weird guy running around off stage doing superhero stuff. By the laws of random encounters and “as fate would have it,” Bug-Morph shows up to foil the robbery.

Connie is an extremely effective combatant—in her suit, she has the fighting skill of a multiple black-belt, super strength, intangibility, a 500-foot leap, and an electrocution touch. But what we learned is a lesson the criminals of New York know very well: you do not fuck with Bug-Morph.

What was the fight like? Most of your other super-on-super battles were pretty brief.

Marvel Super Heroes does a lot of things right, but there’s one wobbly spot in the rules: if two guys start pounding on each other, and each of them is pretty well-armored against the other’s attacks, fights get a little repetitive. Most characters have a “best move,” and losing Health points a little at a time doesn’t change the tactical analysis very much.

For Bug-Morph, that best move was to just splatter acid around all over the place, destroying all kinds of private property in an attempt to bring Connie down. As Connie’s player, Noah tried nearly every fighting move in the book, trying to judiciously switch between intangibility and her electro-grip.

The fight lasted a long while, but when Connie failed to lock Bug-Morph in a wrestling hold, Bug-Morph finally scored a kill result. Connie lost all of her Health, and (having used up all of her Karma in the fight) Connie was dying. Bug-Morph intervened enough to save her life. She’s unconscious, defeated by some random weirdo, when Sam arrived.

Wait—so after ten sessions of tension, of wondering when these two supervillains were gonna meet up to combine forces or kill each other, after all of the crazed stalking and a moral transformation arc and revealing your secret ID—Connie gets knocked out and tied up by… just some guy?

That’s Bug-Morph to you, buster!

But yeah! It’s so stunningly anti-climactic that it almost wraps all the way ‘round to being perfect..

I’d love to know David’s creative process on this: I have no idea if it was, in fact, a random encounter or something he felt like bringing in. What I do know is that the fight could have easily gone the other way—which would have built Connie up as that much more terrifying of a threat, and Sam that much more outmatched. But this particular outcome is something none of us would have consciously chosen. The game itself is participating.

…Okay, so Sam finally tracks down Connie, who’s gone out of her way to make him an enemy, and she’s totally helpless. Now what?

When Sam arrives, he’s figured out by the gobs of acid all around that Bug-Morph is on the scene, so he’s wearing the (armored) costume of the First Responder. Disguised, Sam persuades Bug-Morph that anyone as smart as Connie probably has countermeasures against being knocked out—likely a bomb. The First Responder heroically volunteers to disarm it—“Save yourself, Buggy—I ain’t got much to live for, the doctors said it was Stage IV. Let an old man go out a hero.” Bug-Morph splits, Sam grabs Connie (and most of the money) and runs, detonating part of the area with a cannon. Classic mysterious death scene.

Sam drives Connie to a desolate motel, destroys her super-suit, and ties her up. He has every reason to drag her in to the parole office so he can slip off of their leash.

But when she regains consciousness, Connie quickly sizes up Sam’s dimwitted hope to enlist her genius into his crusade. All she wants in return is a cure for her medical condition. And…. what good is slipping off the leash to save the biosphere when Sam honestly has no ability to do that? Sam already blackmailed a disreputable billionaire to get funding; he negotiated with his sniveling parole officer to stay out of jail; now the woman who threatened his family and killed his pet goose wants to cut a deal to save her skin. What’s more important to Sam: protecting his loved ones or pursuing his old, self-destructive ideals…

Sam unties Connie. They have a deal.

There’s more in that session—I presume the game will continue; there’s a prison riot and a Lich King Arthur and a planet to save—but there you have it: a nice, totally organic story arc in ten sessions.

8 responses to “Halfway Heroes: Supervillain Showdown”

“It’s not like other superhero games,” absolutely, and this villainy thing is why. It’s exciting to see it in play.

The “no cost to switching sides” rule is so nicely done.

There’s no disincentive to switch if you’re at zero Karma.

When is a hero guaranteed to be at zero Karma? When they’ve just killed someone. When is a villain guaranteed to be at zero Karma? When they’ve been imprisoned for many months with little hope of getting out. Maybe now’s a good time to rethink your life choices.

Of course you wind up at zero Karma often enough through regular play. But in those moments especially the game almost sends you an engraved invitation.

(agree!)

Including near-zero, I think. Given some prior fictional context for “maybe I’m a hero/villain,” flushing one’s few remaining points probably isn’t an issue. I can’t guess at a precise value that I, for example, would be willing to flush in such a case, but the points’ units are pretty small, and I doubt I’d hesitate to switch if (i) I wanted to and (ii) my remaining Karma was in the single digits.

A recurring question in these posts has been, “What’s the best way to manage your Karma?” I don’t have an answer, but I do have two comments on the rules.

(1) The character creation section has tiny block of text about “Advancement,” namely improving your abilities and gaining new super powers. Short version: when you gain new Karma for heroic (or villainous) deeds, you can set some aside in a savings account, where it is safe from loss but can only be spent on advancement—which takes forever. (Accumulating, say, 1000 Karma points would take at least 20 sessions of play, and most improvements will cost far more than that.)

This leaves you with a high-level strategic choice. Do you keep the Karma “in your wallet” where it’s available to spend on any roll at any time but also easily lost if you act like a jerk? Or do you squirrel it away into advancement, where it’ll be locked up for most of the campaign but also it means you can act like a complete jackass without fear of consequence? (I can’t think any comics character who acts this way, but it seems like a viable mode of play.)

Offhand, I’d say that having 100 Karma points “in the wallet” means you’re wealthy, or at least comfortable. It’ll get you through one absolutely disastrous roll, or more likely, let you slide through 3-4 difficult moments. But gaining Karma is a lot slower than spending it, so there’s this rhythm of cheating fate and then getting kicked around. (In our most recent session, Connie—still at almost zero Karma after her fight with Bug-Morph—got taken down by a common thug and then arrested.)

The only thing in the 1984 rules that requires more than 100 Karma is kit-bashing an invention. Normally inventing stuff requires spending several hundred Resource points, but if you’re in a hurry and don’t have enough cash, you can convert Karma into Resources on a 1:1 basis to create a one-shot super-tech invention. Given the price of most inventions, this means most Super-Tech guys probably want to have a couple hundred Karma on hand for this exact situation.

Ah! That Karma-to-Resources conversion reminds me that you can run it in reverse, as the Huntsman did in this post. Resources donated to charity become Karma points on a 1:1 basis, literally buying luck. This suggests another way to manage Karma—get really rich. If you save up your Resources, you’re also saving Karma, though with limited “liquidity.” This doesn’t mean much for most characters, who get a small amount of Resources each week and have a pretty low maximum Resource limit. But for folks like Iron Man, Black Panther, Kingpin, and Dr. Doom, it’s an interesting option. And yes, villains explicitly gain Karma for charitable donations, so robbing a bank and giving it all to charity would be Karma-maximizing behavior for them.

!! Did I see that?! That final sentence is the most engraved invitation I could imagine. Shades of the Moon Roach’s catch-phrase: “Unorthodox … economic … revenge. Hssss”

But temptation aside, it so happens that at last week’s Spelens Hus 5E game, we discussed the issues of trade-off when the same currency fueled improvement and momentary bonuses. I want to play Marvel Super Heroes at least as much as you three have done here (Villains & Vigilantes first though), so that I can see whether this arrangement works. Based on reading alone, I’m perturbed, as sequestering Karma from loss seems dodge-ish to me, i.e., its potential loss is an important part of play so why protect it. The incredibly slow improvement similarly strikes me badly, perhaps even as an artifact of the TSR publishing context rather than play-originated design. However, since play experience beats reading-judgment every time, and since this weird wrinkle about Resources clearly alters the whole picture, I’m noting it all for when I finally get to play.

Yes, advancement is the most boring use of Karma, even if it were in reach. The range of play possible from the pursuit and expenditure of both Karma and Resources as well as the options available when Karma is at a deficit are far more interesting.

In our case, Connie wanted to rob a bank to get some Resources to build a device to kill one of the NPCs (Mecano). The bank robbery went badly (she got beat up by Bug-Morph). The Huntsman used the botched bank robbery to get the upper hand on Connie for their first meeting. Connie had enough left over Resources from the bank robbery to invent the device but her Health and Karma were depleted. The device was deployed successfully but she was extremely exposed and ended up getting arrested.

Within that, we had Connie (a villain) and The Huntsman (a hero), agreeing to work together but being at odds with each other — Karmically linked without there even being a shared pool. The Huntsman had warned Connie against going through with her scheme to kill Mecano in a previous session and tried to deal with the issues in his own way (by going to the prison and stopping the riot fomented by Mecano by himself). In such a situation, there’s a risk that the actions of the villain will cause the hero to act against them to preserve their own Karma.

Kit-bashing is a great way for characters to increase their effectiveness, even gaining temporary or permanent new powers by simply creating devices that grant them those powers. The actual improvement rules seem tacked on after the fact, I am inclined to agree that they may indeed by a TSR publishing artifact.

I am quite pleased that we’ve gotten to explore these things. I really like how the ebbs of flows of both Karma and Resources follow the situation quite closely and even drive new situations as the players try to manipulate these currencies to their advantage.

Popularity is kind of the odd man out for the currencies in Marvel Super Heroes. I am coming to suspect that it will work better if it fluctuates a lot more, on the scale of ranks instead of small increases/decreases. The Huntsman’s hero turn was very interesting in that he also came out to the media, revealing his secret identity, in an attempt to increase his Popularity. It’s another short cut to increasing effectiveness without engaging the improvement rules. I love how James tried to increase his Popularity to shorten the power gap between The Huntsman and Connie. I like the possibility that publicity stunts could potentially impact play in the same way that Connie’s bank robbery attempt did.

Just a small correction: Kit-bashing AND invention are a great way to improve effectiveness temporarily and permanently. Kit-bashing is for single use items.

So if James’s Huntsman has typified “The Planner” classification of villain from the MSH Campaign Book, my play of Connie has shown her to be a Maniac who, with enough resources and time, would likely become a Conqueror.

Since she stole the Huntsman’s golden goose, Connie has been on a rampage, reacting to events too quickly to plan beyond the next few hours. While she’s spread plenty of chaos, she’s also borne the brunt of its consequences. She’s had the shit beat out of her twice (first by Bugmorph in a loud, building-melting brawl worthy of her skills, then by a common thug who got in a lucky pistol shot). A decision to not call her father when she really should have lost her precious Karma. And last she saw her she had a couple of HP left and was on her way back to Rykers.

On the other hand, what the general mayhem conceals is that Connie is driven by some very straightforward goals (getting a magical cure for her disease from Sam and/or Cybele, keeping her relationship with the Damerov crime family a positive one being the two main ones). And she has succeeded. Her deal with Sam still holds (though who knows for how long); she quite handily removed a crime lord who threatened the Damerovs from the picture (and had a non-zero chance of making it look like natural causes). She’s also earned an Excellent (and negative) Popularity of -24, giving her lots of potential influence over minions and fellow crooks.

Some of this success is, true, down to her high ability scores. But I think it’s also a testament to the robustness of the system. Gobs of Karma doesn’t guarantee success, and zero Karma doesn’t guarantee failure. How you interact with the Karma system is very much up to player agency. So far, MSH is one hell of a roleplaying game.