I think a small disclaimer is in order: this is not going to be one of those beautiful posts where we celebrate how play comes together and we get to see the various agendas of both characters and players intersect to create meaningful moments that inspire us to push the medium to the limit.

I think a small disclaimer is in order: this is not going to be one of those beautiful posts where we celebrate how play comes together and we get to see the various agendas of both characters and players intersect to create meaningful moments that inspire us to push the medium to the limit.

This is going to be about 6 people staring at a piece of checkered cloth covered in miniatures trying to understand how the rules of this specific game want us to decide what's fair and what isn't, and where we go from there, and if any game that actually decides to tackle these issues and make them a meaningful part of play actually gets it right.

As I've mentioned in the past, we've been playing Pathfinder 2 since november 2019, with many small pauses and issues tied to COVID. Some of it was live, some of it was through Roll20. All of this back and forth (combined with my rampant senility) contributed to a learning process that wasn't particularly smooth.

And Pathfinder 2nd edition is one of those games. The rulebook is about 650 pages thick, and the "Playing the game" chapter starts on page 450-something.

This is an important disclaimer because it's a bad habit to criticize a game that you're not playing properly, and as we're not playing this at 100% accuracy, most of the time when the experience stumbles we (me) aren't exempt from blame.

However, last night something happened that led us on one of those goose chases across manuals that inevitably end with me scratching my head.

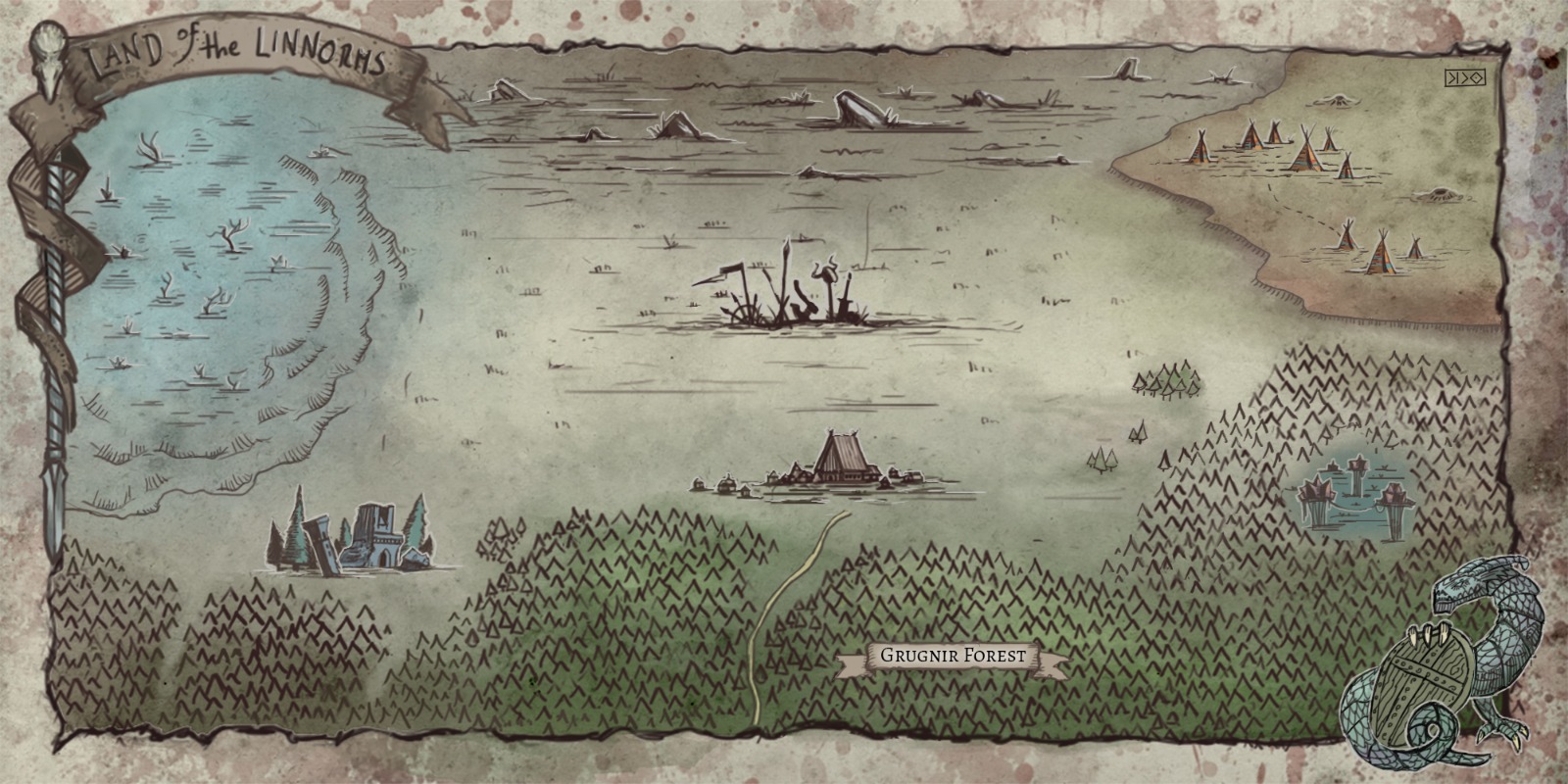

Small premise: the "story so far" is rather simple. The group is moving in the wake of a small raiding band that has been wreaking having in a region known as "the lands of the Linnorm Kings", which is basically fantasy Skandinavia with faux vikings who hunt wingless dragons to prove they're worthy of being kings. Risky business, and in fact the principal issue seems to be (for once) the power vacuum caused by a sever lack of people who seem to have what it takes to kill a skyscraper sized lizard. Queen White Estrid is a notable exception – not only she defeated a linnorm, but she tamed it. One of the players drunk some blood and had a vision of the queen clashing with the invaders, and the party choose to move to where the battle seems to have taken place.

Last session began with the group emerging from the forests after having found a bizzarre summoning gate made of wood and bone, and signs of the presence of some sacrifices in the area, and a massive beast that emerged from the portal. All of this is fairly old – at least a few weeks.

They spot a town sitting on a nearby hill, but no real sign of life in the plains. The town itself is walled and everything outside the walls is abandoned, apparently.

On the way the stumble on a few dead buffalos and they decide to investigate what looks like a small campfire. There they meet a bizzarre middle aged woman dressed in a mix of southern and winter clothes, that informs them that the vale is plagued with the presence of a "beast" that is hunting and killing people left and right. A big battle happened about 5 weeks ago, and the jarl of Jorvik (the town they saw) died in the battle. The jarl's sons took over the ruling duty, but in the confusion of it all the beast appeared, the body count increased and now everyone lives in terror. The woman (who travels with a bizzarre bronze cube that moves on mechanical legs) seems to be incredibly socially awkward (not in a "cute" way) and not particularly world-savvy, and has been refused access to the safety of the town walls before. So she asks the player to escort her in exchange for information, and they agree.

The rest of the session was about the group interacting with the fragmented town leadership, discovering about the conflicts in the ruling family, making friends (few) and enemies (many), getting the lay of the land and discovering a few places of interest, and finally bargaining for a reward in case they manage to eliminate this "beast" (something they still need to do if they want to reach the place they're actually looking for).

This session starts out with the group following the ranger Snaga who's ready to pick up tracks and a go hunt for monsters. They're joined by a small band of mercenary dwarves who have been hired by the town leadership and don't want to be left out of the glory, and they immediately set out to explore.

I have prepared a small map of the land, which I'll upload because it's a beautiful piece of original art made by a friend:

So I have my points of interests, and we're ready to "sandbox" it.

We've discussed this extensively recently, so I'll cut it short: "sandbox" means very little in this case, it's an excuse for having prepared encounters that the players may stumble up. "Improvising" a situation in PF2 isn't trivial, or at least it isn't for me. There's a very precise (at least formally) mathematical process to building rosters for doable combats, and since combat is such an elaborate, tactical and time consuming process, you can't really slap some creatures together and hope people will have a good time. It's an important aspect of this type of game – once the combat minigame is on, it's going to last, it's going to require attention and decision making, and it's going to force people to suffer through everyone else's decision making. There's a dozen actors on the battlemap and your pawn is going to get a fraction of the time – you want your moment to be exciting, and consequential, and you want to feel like your decisions mattered and that victory or defeat depended on you too. At least, that's how my players feel, so even if there's no prescription for a certain encounter to end in combat, I tend to make sure that if it does such combat can honor the commitment of the game to become a skirmishing wargame for an hour or so.

In PF2, this requires preparation, and so here we are. I have my family of wandering ogres who came here to pillage the battlegrounds or perhaps even sell mercenary work who clashed with the beast and are still reeling from it, a few packs of carrion-eaters attracted from the remains of such a large battle, a druidic grove with a plan to perform an ancient blood ritual that will summon a Roc to hopefully carry (literally) the beast far away, and so on.

I roll a few dices to see where the tracks lead, and the group decides to explore the grounds where the druids have been hiding. Now as I said, don't look at this game as a virtuous application of best practices. There's everything here, including intuitive continuity. The players are exploring the battleground (and realizing this isn't the battle they had visions about – that has yet to happen! Prophecy! Railro… ahem) and they stumble upon tracks of dragged corpses. They follow them into the woods, and spot 3 bodies at the bottom of a big ravine.

And here we get to the matter of things: perception. That fine process that (in this type of game) tells us what players see, what they don't, who gets to do what about it and so on. Do they find the thing? Do they spot the ambusher? Who goes first?

Here lies the first "problem": it's called Perception (or Spot, or Scan, or Observe, depending on the game) but it's really the process of seeing what happens next. It's the textbook example of a skill check becoming a framing technique: you roll to see what kind of scene you're going to play. And when the roll returns a result that isn't usable, you're stuck with not knowing what to play. Pathfinder 2 seems to acknowledge this (I don't know about solving or being functional about it) and it bases the ordering process in and out of combat on Perception rather than "dexterity" or "initiative". The more you understand what's going in on, the sooner you get to partecipate.

The very transparent manifestation of the problem lies (and I guess people will immediately recognize it) in the fact that very moment you ask anybody to roll to see something (or if you start to furiously rolling dice behind your GM screen and compare them to those "Passive Perception" scores that are the rage these days) it's impossible to go back to any scenario where the idea that there isn't actually anything to spot or find is acceptable.

My groups rarely finds this process satisfying, to the point that while most people at the table consider it a necessary part of this type of experience, we've come to appreciate games that simply skip it. But despite the blunder I'm going to describe (which is partly caused by some murk in the rules), I have to credit PF2 for seeing this problem and trying to address it in creative ways.

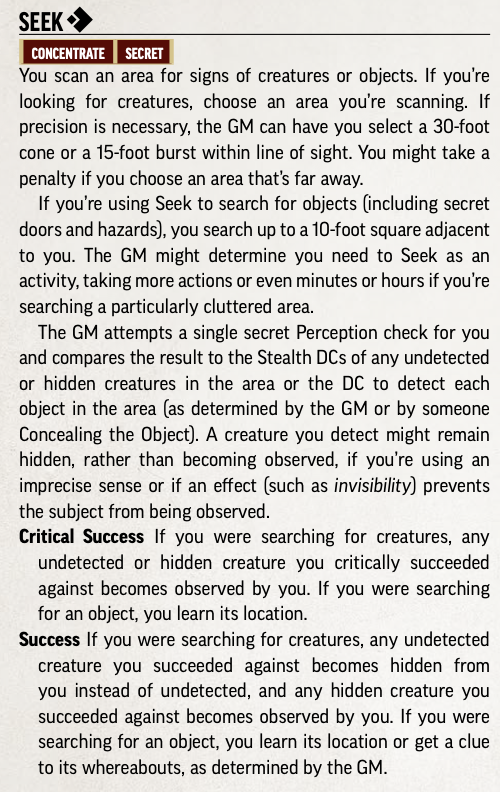

Anyways, the group is looking for tracks and scouting the woods and of course some scouts from the druidic circle are hiding in the bushes (there's a shambler laying under the corpses, setting up a trap, and a few leshy – think gnomes, but made of vegetation). At this point I have players roll Perception, while I roll stealth for the opposition. After the game, I went back to read the rules, and I realized that while the correct procedure is unclear, this definitely is wrong. I should have just had a "secret" Perception roll from the players vs the Stealth DC of the monsters (these DCs are equal to taking 10 on the roll on an opposed roll).

Anyways, two of the players get pretty impressive results (33 and 34 total) and I get a 32 for stealth. Despite the initial mistake, I handle things right from here on. The way Pathfinder 2 handles awareness is somewhat complicated but interesting.

There's three fundamental states two creatures can be relative to each other: undetected, hidden or observed. The spectrum is "I don't know you're here", "I know you're here but I can't see you nor I know where you actually are", "I'm looking at you right now". The Seek action (using Perception) allows you to attempt a roll to move one step on the spectrum, and the Sneak action (using Stealth) does the same in reverse. It's a little subsystem that is actually really functional once a situation has started and has proved to be a definite improvement from the very binary states you generally find in games with this type approach.

In PF2 you get a critical success by rolling a natural 20 or by beating the DC by 10 or more. None of this happened, so the creatures stop being undetected and become hidden. I tell players they see something small move in the bushes. What happens next baffled me. They look at each other and say "Oh well, let's go on". They step into the ravine, leaving the dwarves to keep guard. When they reach the bodies, the woodland creatures (who didn't know they had been spotted) spring the "ambush", which the players are prepared for. The druidess that is leading them was expecting a quick surrender and possibly an interrogation, but the characters won't have any of that, and a moment later we're in the middle of monks punching shamblers, wizards using dark magic against horned archons, and a particularly angry owlbear mauling dwarves. How the combat went is another matter entirely (it was fine, it was fun).

After the game, the ranger player lets out an "Well, it's funny cause we rolled a 34 and we still walked right into it". This led to a discussion, and once again I pointed out that the game probably expected them to follow that first Perception check with another (to go from Hidden to Observed) but we still didn't have enough familiarity with the rules I guess. But I'm more interested in the mental state that led them to go from "we didn't roll high enough" to "we'll just go on and trigger the encounter".

We all agreed that the situation depicted – a trail of blood, the remains of a battlefield with crows and all that, sinister woods and misterious shadows lurking out of sight. It's a narrative trope that works so well in most mediums – the heroes move cautiously, tension builds, etc. Or the opposite. The characters stay hiding, waiting for the opportune moment… and yet it seems so difficult to make it work in roleplaying games, expecially this type of game where there's so much riding on who gets to go first.

The other poster boy example for this type of situation – hinging on the characters noticing or not noticing something that leads to a development – is the hidden book that contains the one bit of information the group needs. How satisfying it is to read about our investigator finally stumbling upon it. But in game? Either people find the book (the Perception check was a success!) or they find out they haven't found it (the Perception check was a failure… can we roll to search again? What if we send someone else? Can we demolish the room? Add whatever form of escalation or negotiation that fundamentally sums up to "why did we bother rolling a dice?".

I wouldn't have made such a meandering post if the main takeaway from the discussion we had at the table wasn't "Well, this clearly didn't work as it should have, but we're interested in what the situation was, so… how could we make this work?". I'm really curious about how people feel about these things, about which games handle the process of introducing what the characters don't see/know gracefully, how you handle the fact that characters are facing the unknown but players are very well aware of what the dice have and haven't told us, and so on.

7 responses to “A Matter of Perception”

Ah Perception / Scan – We Meet Again

Is that the oldest question in role-playing? If not it is the most basic. And it is inextricable from the content, because to engage with the content we have to somehow find it in the first place. At the same time, there is a strong desire for some players to be surprised by content. I am one of those players; even if I notice THE STUFF, I want it to surprise me. I want a sense of wonder or "oh shit" as those are memorable moments for me. I want to be suprised, even if my character knows that getting surprised can be deadly. Off the top of my head I am cannot think of a system that is designed for this kind of content that does perception well. I like how % systems like BRP have their skills. It feels more pass fail, but "Bob failed, can I make a scan roll?" is still common.

I just want to lay out some thoughts as shorts or else I would go on forever.

An issue I think is baked into D20, D&D5, and maybe most games. – Bob failed their roll, okay, I will roll the same thing because the group cannot fail. Why can the group not fail?

A slave to idom = Poor content design. Please do not take this as a shot at your content, which sounds amazing. I think this is something many of us do poorly. Too much content relies on tropes. There may be no escaping this. A place that looks good for an ambush probably has an ambush and if it doesn't, the players become suspicious. "Oh it's coming".

Trust issues – something we spoke about in the Lamentations game. If I roll well and find nothing, is the GM using some loophole to hide STUFF from me? Now I do not think this is always bad; it gets back to why can the party not fail. System matters here too. In LotFP or the older basic D&D sets, you find something on a 1 in 6. Finally rolling that 1 and then finding nothing feels disappointing.

All the solutions I have come up with are ad-hoc because the D20/PF/D&D5 systems build hypercompetent characters very quickly. By 5th level they are rolling into the 20s and 30s and you have to either set things imposisbly high or accept that you cannot hide anything from them. Which gets back to why did you have them roll in the first place?

Clues as Rewards – if the players defeat a trap, make good preparations against an ambush, give detailed info on how they are searching without piling on skills, I give clues as a kind of treasure.

Asserting Authority – I am sure this might wrankle some feathers, but I assert authority over the situaion. I will ask Bob for a roll. If Bob fails or succeeds, no one else gets a roll. My players have bought into this by specializing: one person handles Investigates and one handles Perception as well, they assist one another. This has greatly improved things for me.

An issue I think is baked

That's a very good question that's very difficult to answer to.

I think there's two different problems conflating here.

One is that a lot of games implement binary resolution systems, tell you that you can succeed or fail at the task at hand, and then proceed to focus on what happens when you succeed. Failure is handwaved away and rarely considered – in fact, most negative events that can happen to your character are consequences of someone else's success, rather than your own failure. So if the game doesn't bother to make failure a usable outcome (in this case I consider usable as anything that tells you "you failed, so this and this happen"; we generally get "You fail. Code line broken. Find something else to do"), we tend to get lost when it happens.

The second problem is how we create content – you said more or less everything on this already, but the problem runs deep. The function of a secret door is being found. Sure, old modules contrasted this problem by implementing quantity and redudancy: you missed the secret door and a ton of content, but that wasn't necessary and there's like 10, 15 more secret doors in just this one floor of Undermountain!

However, for the type of content we're discussing, that doesn't really solve things. Players got interested in a series of random killings that happened next to the various sewer entrances in town, so we created a serial killer antagonist, gave her motivations, and an hiding spot in the sewers, but she concealed the entrance, and if players find it we get the tense, Seven-esque scene of exploring the killer's lair, if they don't we'll feel like we missed out. The newest version of The Enemy Within (a famous Warhammer Fantasy mega adventure, that was semi-recently redone for the 3rd edition of the game) has something like this. One character isn't what she seems, and there's several clues that the players can miss. The game "solves" this by giving you A LOT of clues, so if the players are just a bit attentive, they'll uncover the culprit with a landslide of evidence, turning the whodunnit from having a shocking revelation to "why don't people see it's this guy? It's obvious".

If the story is that of a few heroes hunting for a serial killer, they need to catch him… or he needs to win. Jack the Ripper was never caught and we still write fiction about him. Again, Seven. Recently Ron played a game called The Hour Between Dog and Wolf (I think) that focused on similar themes – there things work because a player IS the serial killer.

I could write for hours about this and probably I would get nowhere. For the game I'm writing, I decided to tackle this by analizing what failure is in fiction and translating it into mechanics. Another useful (in my opinion) way to approach the issue is looking at what we consider success. If we write success in our preparation or we propose it (as players) before we roll as "I'm going to get all this and then more", the failure means being denied everything, and I need to try until I succeed (with all the problems you described).

If we look at things a bit differently, and say "I want to open the locked door", we can define succees as "I open the door quickly and easily" and failure as "It takes me forever, and I break two different sets of lockpicks to do it". It's a matter of shifting from "thing doesn't happen" to "thing doesn't happen as I wanted it to happen".

If we're creating content in a way that makes certain events necessary, it is (in my opinion) a potential solution that makes that roll an opportunity instead of a potentially frustrating formality.

This is pretty much what happened in my game. My disappointment stems from the fact that I felt like people were walking into the "ambush" because they thought I needed them to walk into the ambush… for some reason. It was frustrating. I suspect Ron's frustration with us at the end of the Lamentations playtest had a similar origin.

I do this too.

Pathfinder 2 does tackle the issue (I may not 100% onboard with the answers, but trust me – in its 600+ pages, Pathfinder 2 tackles everything) by creating precise rules for group checks and specific actions people can take – like Following the Leader, for example, which allows you to follow the rogue who's sneaking around without simply having to roll your embarassing Stealth check.

Some questions to ask

From what I understand, the result means that they know there is something significant and their locations in terms of squares, but not more precisely. This seems to be the definition of the hidden condition, at least: https://2e.aonprd.com/Conditions.aspx?ID=22

The players did set up guards and then walked into it, and thus succeeding at the perception checks had an effect on the situation, from what I understand.

The questions:

1. Did you all in fact know that you have this much information?

2. Did the players walk willfully and knowingly into the ambush or whatever was waiting for them? What did they expect to happen as a consequence of their actions?

Yes, the process is actually

Yes, the process is actually fairly simple. You take the Seek action, and if you succeed you know if there's anything lurking around (they go from Undetected to Hidden). Now you either saw the creature (within the radius) or at least you know it's there.

So regarding the question:

1. I can't say for all of them. This part of the rules was still a bit fuzzy in our mind. Next time this happens, everyone will know precisely what's going on.

2. This is the part that bothers me. They acted like the process was over (we rolled to see beasts, we saw there's something but we didn't know what, we'll just walk in because we want to have a combat). The characters (not the players) are fairly confident in their means, but in no way careless. It was just a weird situation.

I hink you should discuss

I hink you should discuss question number two in your group, if they are amenable to thinking about their play.

One issue which seems to be

One issue which seems to be important for this whole thing is the framing of "walking through a spooky forest." Are characters moving around on a grid or is it so called "theater of the mind" or whatever? If the rule is as Tommi suggests, the game may be assuming that if you're in a dungeon you're on a grid, period.

If you look at the small

If you look at the small picture I posted that details how the rules for "seeing things" work, I would say the game assumes everything is always happening on a grid. It makes specific reference to feet and cones and squares. The entire game "thinks" in squares, so you need to be fairly agile in either abstracting that in TotM terms or saying "this happens here, 25 ft from you, and in the area you scan there's 3 skeletons".

You see this happen frequently when someone uses a spell.

DM: "There's some thugs trying to jump on a coach at the end of the alley"

Wizard: "I launch a fireball and blast them all!"

And this point either the DM handwaves everything, and decides who's where and just move on, or suddenly you need to detail how long the alley was, and how wide, and can we place the fireball in a spot that gets all the thugs but not the coach, because the princess is on the coach, and so on.