Living Alchemy

Living Alchemy

I've been working on a roleplaying game for half my life. I started it in the summer before college, sitting in the empty campus of UNL. I was about to leave for a another state, bitter about my life, bitter about leaving it. But this isn't about that. I recently finished an eight session campaign using the system I built. I thought I'd tell you about it.

Living Alchemy is an emergent storytelling game. Virtually nothing is prepped. Virtually no elements are introduced into the game by the gamemaster. Not only do plots emerge organically, but the game naturally builds towards intense situations. I've been told it feels like suffocation. The players play afflicted characters- addicts, schizophrenics, people consumed by revenge or devotion. It draws from the the romantics- the morose poet, the Byronic hero, its interest in the occult and the psychological.

My campaign had one player, my brother R who has played games with me for years and shares my interest in literature.

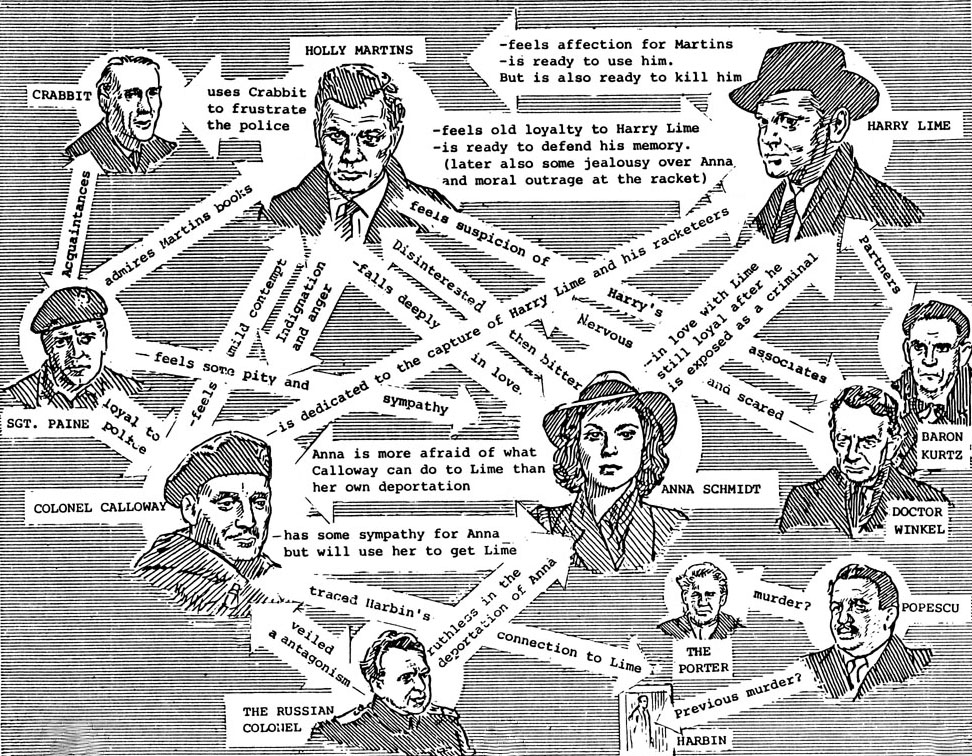

I've been working on making organic story-oriented play more accessible. For Bright Eyes, I tried something new- a variation of the character map technique but specifically tailored for Living Alchemy. I began with a simple character map (in fact, just three people and three locations) and let the players attach themselves to one of the characters. Relationships are always of the following types: Adversary, Master, Apprentice, Servant, Romantic, or Family. Relationships are conceived as asymmetrical and almost assured to develop through play.

The Module

My solution was to start with an antagonist and let the players frame the conflict with respect to him. Enter King Greyhand.

Artist: Grobelski

I saw this picture and a character sprang to mind immediately. Like the player character's, the antagonist begins play with an affliction. He was once a powerful king who conquered the Wildlands, the country the game takes place in. The Wildlands was home to the fantasy races we all know, but Greyhand conquered it and installed himself as King. Like a player character, Greyhand has an affliction- Broken. He has grown fat and weak though his power and strength once matched that of trolls. He draws very much from The Kingpin from the TV show Daredevil- the personification of neo-liberal gentrification. Essentially, I took the Kingpin, made him a colonialist, and broke him.

The module has two other characters. Priestess Reyla, Greyhand's former general and King Aeshma. Aeshma is a troll who rallied the fantasy races of the Wildlands together to oppose Greyhand's conquest, unsuccessfully. He lost his arm and sits in Greyhand's dungeon feeling sad.

Greyhand is not only old and fat, but impotent as well. His goal is to hire an alchemist to help create a child to carry on his legacy.

The Protagonist

That's the entire relationship map of the module. R was filled with ideas immediately. He picked up on the racial undertones quickly which I had to push back on. My framing was explicitly colonialist, the "happy" kind of colonialism. Greyhand thinks he's a civilizing king. He has brought peace to this country and begun the selfless process of industrializing and educating.

R hooked into this and made his character. He was an elf whose original name was Lorend of the Seven Winds, but his human name was Laurence the Innocent. The affliction he chose was Outcasted– an elf ascending the ranks of human society as an alchemist and professor. He was once Aeshma's adoptive son- vowing to unseat Greyhand at any cost. He introduced a new character into the game to act as his patron- An abbot named Milo who ran a center for educating the Wildlings, reshaping them into useful workers.

Laurence would prove to be one of the best player characters I've ever had in one of my games. A near-genius plagued by an overwhelming longing for companionship whose every action undermined that desire. Associating Outcast (one of nine afflictions) with elf was entirely R's idea and it was the fulcrum for the whole campaign.

Session 1

The game begins in the Abbey of Unification, the reeducation center run by Abbot Milo. Laurence serves as a professor under him. His first action was to recruit one of his students to act as his lackey- a reformed criminal named Jessup Freeelf.

Living Alchemy allows players to introduce new elements into the game using special abilities. Jessup was introduced using the ability hire. The abilities of the hire and the framing of the relationship are established using the mechanics. We established that Laurence had something over him (he desperately needed help with his studies), which made the roll extra difficult.

Laurence begins a series of secret alchemical experiments to enhance his own intelligence and to create enhanced animals that might be presented to the King. One of these experiments goes wrong. R misses an easy roll with his absurdly deep pool.

(Rolls in Living Alchemy are often successful – possibly 85% of the time. Players play an important role in setting the difficulty. If rolls are too hard, they won't be attempted.)

A transmuted horse bites Laurence's leg and escapes into the Abbey, biting and terrifying students before being put down. The abbot considers this a deep betrayal and, after healing Laurence, begins treating him almost like a prisoner. In particular, he begins taking Laurence's transmuted animals to King Greyhand, improving his own standing with the King.

R conceives a strategy. He will exhaust himself to create an incredible transmuted animal, present it to the King and treat his affliction with the King's praise. This is a masterful plan, taking advantage of the narrative to achieve a mechanical advantage. In Part II, I'll show you how it fails.

7 responses to “The Story Module (Part I of III)”

Question about “Hire”

That sounds like a great ability. Is that available to any character, has to be chosen at character creation, or was it something more organic and came up in the moment? Why make the roll more difficult? Thanks!

The Hire ability is available

The Hire ability is available to every character at every time. It's one of the game's 7 special abilities.

A character's dice pools are chosen at character creation and are based upon their class- either Patron (high class), Scholar (middle class), or Agent (lower class).

Agents have higher dice pools for actiony lower-class abilities- Solider, Beggar, Artist, things like that. These aren't associated with special abilities.

Scholars have dice pools associated with some powerful special abilities allowing them to perform services for patrons. They have Physician, Alchemist, Diviner, Advocate. Each of these special abilities requires resources, generally provided by a patron.

Patrons have just two dice pools, associated with Hiring and Borrowing resources. They have the best access to special resources.

In the game, Laurence is a Scholar who used Hire at a measily 2D. Hire has three possible targets-

6 – The introduced character desperately needs something you have. (Laurence chose this for Jessup, needing Laurence's help to stay in his program.)

5 – Choose a goal for your hireling.

4 – Choose a background detail for the hireling. (Laurence chose this)

The more targets you hit, the more dice the hireling has. However, they are their own character with their own goals and objectives. The targets you hit has a major effect on the framing of your relationship with them. In Laurence's situation, he needed someone who had the skills he lacked (he was in a solo game, and as a scholar he lacked the rough and tuble abilities that Jessup has as a criminal), but also someone who he could trust.

Nothing useful to add

Hi there! Just wanted to jump in and say that Living Alchemy sounds really, really cool! If you're ever looking for playtesters, count me in!

That’s great to hear. Stay

That's great to hear. Stay tuned for part II where I'll show some what all this stuff is leading to.

Emerging

Let’s do some unkind damage to your term “emergent,” which is an abomination before God and in the sight of all His angels.

Well, maybe not that bad. I maintain that this term has been horribly co-opted to be used for situational components (“scenario”) when it is intended or valued as the outcomes of play procedures (“plot”). People think they will get the latter by pumping up and widely distributing the former.

Here’s the point about situational components: that who invents them does not matter. I know this flies in the face of every indie mantra and I know every kneejerk response. “But if everyone provides the situation’s features, then everyone will be invested in it and I won’t have to ‘make’ them care!” It’s almost true, but investment and caring are less complicated than that – just the tiniest bit is enough when the medium of play is functional, and when that medium isn’t functional, then maximal provision of backstory and details by the maximum of people isn’t going to keep play from failing out.

Nor does it matter whether these features are established before play begins or during its course. Again, I’ve heard every insistence that somehow it’s more exciting or wonderful to invent who murdered the butler during play rather than before it, but enough. It’s neither more so nor less so. “Emergence” isn’t about when back-story or similar features are made up.

Here’s my summary about situational components. As long as the game has any working functions for (1) which situational components are established by whom, and (2) when they are made up and, more importantly, brought into play, then it’s fine. Yes, exactly how it is done for any game isn’t trivial in terms of the experience. But it is trivial in terms of importance. Your particular desire for #1 to be spread abour the participants is therefore perfectly viable and, as Maud would say, “And proud we are of all of them,” but it is not special in terms of a desired investment in play or of an impact upon played events.

Now to discuss “emergence” of any conceivable value, which is to say, for plot actually to be created via play in an intuitive and active, without being forced and performative. Think of plot or “story” as the leftover wake or path of what we did. Therefore instead of who made up any given noun that happens to be in play, the question is what we (everyone playing) do with them all. We need to look at the procedures of activity – the verbs.

To focus on these procedures, I’ll start with my own excitement about your ‘pitch’ – all that stuff about schizophrenic and Byronic – because it puts me all the way over the edge in terms of wanting to sign up for the next playtest. It’s great! That’s not trivial, it’s absolutely required. When I see it, or rather, see it in others (as with R) or experience it myself, I know that “this game demands to be designed.”

The good news continues, as clearly your “something new” character map method worked out very nicely for this playtest, and no one could or should object to it … but I do want to provide you with a serious warning about this technique.

It can very easily slide into providing a 90% finished situation, full of characters whose interrelations and goals are easily played but so fixed in place that the players merely adopt them and act them out. It means that plot-outcomes, “real” story if you will, are so ready to be produced that they operate as a script, or at best, choose-your-own-ending, in either case to be depicted and completed with thespian verve but nothing else.

This problem’s seductive feature is that it will, indeed, produce a capital-S Story. It’s perfect for demonstration play which everyone walks away from saying, “That was so awesome!” And that, exactly, is its worst feature.

I repeat that I’m offering this as a warning. Not as a diagnosis. Given that you played for eight sessions, it’s unlikely that my grim portrait applied to this experience. But! If you take the wrong lesson from it, and choose to focus on that starting map as a kind of dinner theater briefing for “what to do,” then you’ll end up down the wrong road. I speak from many bitter experiences, watching early designs produce fun (or cathartic, if the word “fun” bothers you), vivid, and above all unprogrammed story outcomes, and then through the designer seeking to guarantee this effect, turn into lifeless exercises that merely provide the final phrases to a fully-authored paragraph.

In reflecting upon your eight sessions, I urge you to consider the intermediate period of play, when the relatively objective relationships of the character map operated as a framework for the real relationships – how do I really feel, what shall I really do about it – to develop.

As far as I can tell, I

As far as I can tell, I enthusiastically agree with each of your points. Of course, it’s easier to call play “organic” or “emergent” than to substantiate it. I’ll briefly outline some of my thoughts on emergent play, although my ideas are incomplete. At the end I still won’t have anything like necessary or sufficient conditions for it.

There has been a widespread use of the term “emergent” in games circles. It’s role has been primarily to distinguish games like chess from games like rock-paper-scissors. I like the term because it highlights the connection between games and complex systems, where emergence is most commonly studied.

In complex systems, emergence is broadly defined as “having traits that are not apparent from its components in isolation but which result from the interactions, dependencies, or relationships they form when placed together in a system.” Complex systems tend to be those with many interacting parts. They’re studied in physics, and are especially important to understand phenomena related to phase-change.

With regards to games and RPGs specifically, one of the problems I see is the issue of “state.” In complex systems, a model’s “state” is defined formally. In physics, it’s usually encapsulated in the energies, and momenta (linear/angular) of a system and its components. When it comes to games, however, this is all thrown out the window.

Is a game like “see who can hold their breath the longest” an emergent game? What are the relevant “state variables”? The state of a game can be conceived to include the physical and mental condition of the participants and even their entire histories of interaction. In a tabletop RPG, the situation is quite difficult because the issue of state is enormously complex. Often, it has been burdened by harmful conceptions, “There’s the system part and the roleplaying part.” However, people often feel that some aspects of state are more privileged than others. Whether whatever is written on their character sheets (especially within the margins of a printed template) or particularly well-defined it’s usually considered particularly important. Often games will have rules linking some notion of state to player participation (you can no longer play this character if some statistic drops below some threshold).

I’ll simply reiterate that defining “emergence” is difficult for at least two reasons (1) The difficulty of defining emergence in formal systems (2) The difficulty of determining the relevant “state variable”.

In general, my best attempt to cut through these difficulties has been to place my focus on player decisions. My predominant interest in games is to see interesting situations arise and see how people face them. In chess, this clearly happens (chess has nearly limitless distinct positions that are challenging) and I think in the “hold your breath” game it doesn’t.

When I say “Living Alchemy is an emergent storytelling game” I’m trying to say something like the following:

(1) Living Alchemy is a game where, by following the rules, interesting/challenging situations will naturally arise. By interesting, I mean they will likely require reconceiving the situation in a new way, the employment of strategies, or both. This is the “emergent part”.

(2) The series of situations and decisions will form a narrative and, more specifically, a story. More specifically, it will be a story about a character dealing with some internal problem (such as addiction, growing older, having a perverse attraction to someone), and how they change to cope with it.

I’ll try to connect all this to situational components specifically. My understanding is that you’re using “situation components” to mean things like characters, and locations. Please correct me if I’m wrong. Again, I emphatically agree that who introduces situational components is not at issue.

I will also say that Living Alchemy as an emergent game is completely separate from my use of a relationship map. The relationship map and the process of creating the protagonists and integrating them into the game has been towards making the game easier to play, more accessible, and perhaps substantiating themes. It’s also notable that I’ve run this module twice, once here, once with a group of four players that lasted 7 sessions.

In Part II, I’ll go into more detail about all these “interesting situations” I’m talking about, how the game conceives of situation components, how they’re introduced, etc.

All good thoughts. I’m

All good thoughts. I'm looking forward to reading about exactly what you're describing, as also mentioned as the teaser to part 2, when things did not go well for our principal character.

For purposes of sharing more thoughts, not as debate or trying to convince anyone, I have chosen to regard both "role-playing" and "games" as legacy terms, with no particular meaning aside from pointing to one of the videos and saying "like that."