Ok, so here’s what I’ve been doing in my D&D campaign. I’m putting it here because I want to contrast it with the Star Wars game, looking for deeper understanding and analysis.

Anyway, the basic setting is that the world is currently ruled by a decadent, decaying Elven Empire, where humans are the main slave race; what’s unknown to most is that this world and everyone in it is threatened by the Others, Lovecraftian-like entities who tempt followers with dreams of power. Rifts in the world have formed that allow some of these extra-planar entities through, and these rifts are getting wider; to stop them, the PCs need to gather five magic medallions that have helped seal these rifts in the past. This background was all established during the first few sessions.

So what I want to talk about is the most recent 3-4 sessions (we’ve been playing about a year now, so a lot has happened since the start, but this is what’s most relevant I think). In pursuit of one of the ancient medallions, the party (mostly humans, one half-elf) makes its way to the Elven city of Riverton. There was basically no way I could anticipate what the players would do here, so I prepped by sketching out a quick map of the city, adding a couple of areas of interest, and creating points of conflict – Elvish politics with different houses jockeying for power, human rebels, Elvish Mage Hunters and Inquisitors searching for illegal human magic-users, a criminal underground led by someone referred to in hushed tones as One-Eye (he’s a beholder, haha), and servants of the Others who are also in pursuit of the medallions. The only event I prepped was that Hassan’s Raiders (the human rebels) would try to stage an uprising at the next Arena Game (which is basically a sadistic game show, where slaves who failed in their duties have to face various monsters in the arena, and usually die badly). Then I let the players have at it.

During play, in contrast to the Star Wars game, with few exceptions I felt no pressure for any particular session to have any kind of climax, or to have anything in particular happen by any specific time. I just reacted to what the players did as made sense at the time, given who they were interacting with and their motivations. The first Riverton session didn’t have much of a climax, as mostly the players just learned the lay of the land (their characters had never seen a city before), and tried to figure out a way to get into the city. The next session was quite exciting, as they followed clues, tried to make contact with the rebels, and wound up fighting the beholder. They killed it, but their use of magic attracted Mage Hunters, who attacked and captured one of the PCs (the Ranger), so the session ended on a cliffhanger – and again, none of this was planned to happen.

Next, the PCs (who thought their ranger friend was dead) help foment a slave uprising with the Raiders when they attack the arena; they capture the game show host and abscond with him to a secret rebel hideout. As elvish troops try to put down the rebellion, the servants of the Others, concerned that the party is getting too close to obtaining another medallion, respond by unleashing an undead plague on the city. The characters (now with the rebels), want to help get the civilians out of the city before too many of them fall victim to the undead – and decide to take over the docks and commandeer every ship they can, load them up with refugees, and escape down the river. Before they can attack the docks, though, the party learns that their PC comrade is alive, and being held in the Central Tower.

While captive in the Tower’s dungeon, the Ranger is reunited with his long-lost father, who is now a head slave, and who pleads with him to voluntarily accept slavery and join this Elvish house – otherwise, he’ll surely be executed as a rebel. After a lot of arguing back and forth, and the exchange of harsh words, the PC refuses. When elvish guards come for the Ranger, the father begs to take his son’s place; an elvish Inquisitor says she’ll take this under consideration, and takes the father away. I added this bit about the father in on the fly, because the poor player was sitting with nothing much to do while his character was in jail (note: in his backstory, the player had previously established that his father had been missing for years).

Next session, while Hassan’s Raiders begin their assault on the docks, the party rushes to rescue their friend. Once in the Tower, one of them (the Sorcerer) breaks off and sneaks into the Hall of Records, intent on finding out who killed his family when he was a young child (the trauma of it unleashed his wild magic for the first time, and he knows it was elves from this city who did it). Now, I hadn’t prepped a Hall of Records, but when the player asked me if there was one (and told me why he was looking for it), I just went with it and said yes. It took little effort to figure out where in the Tower it was, and what kind of guards, etc. it had.

The rest of the group sneaks into the dungeon, but Mage Hunters are waiting for them – and there’s a major battle. The PCs emerge victorious but injured, and get the Ranger out of his chains. The Sorcerer (with the judicious use of stealth and invisibility) successfully steals a scroll detailing the events around his family’s death, but has no time to read it as he hastens to rejoin the others in the Tower’s dungeon. Meanwhile, a large swarm of undead surround the Tower and try to break in. Elvish troops bar the main doors, but cracks are beginning to appear in the wood as the howling undead press against it.

That’s where things ended last session, another cliffhanger, also completely unplanned. I have no idea what will happen next session, either – will the characters work with the elves against the undead, or try to fireball the lot of them? Will they leave that PC’s father for dead? I also don’t know if there’s another way out of the tower; if the players actively try to find a secret passage or something, I’ll create one on the fly.

So as DM I felt overall more relaxed during these sessions than I did during the Star Wars one-shot, where I felt under more pressure to ensure a complete narrative arc happened. These sessions did require some initial prep, but the prep I did was mostly fun. Although I wasn’t consciously thinking of them in these terms at the time, I wonder if any of these events count as bangs, specifically: Hassan’s Raiders assault on the arena, and the Mage Hunter ambush in the dungeon?

I did feel a bit of pressure sometimes to do something extra, when it looked like the players were spinning their wheels, or otherwise when the game started to get slow. Perhaps these are occasions when bangs can be put to good use? What I actually did was usually call for a roll, investigation or something, and use that as an excuse to feed the players some interesting information (“you rolled a high perception? You notice a scruffy-looking beggar has been staring intently at you, and is now sneaking off towards an imperial guard”). Oh, I also unleashed the undead plague when the players stopped for a long rest 🙂

How satisfied was I with the sessions? Well, everyone seemed to enjoy themselves – two of the players changed their vacation schedule to accommodate the game, so it seems people are getting something out of it. The story that emerged is exciting and interesting to me, but it’s not quite as fulfilling (yet) as the Star Wars game was, with those dramatic personal conflicts at the end.

My guess from reading Circle of Hands and the Annotated Sorcerer, is that the way I GMed these sessions of D&D is a lot closer to running one of them than it is to intuitive continuity. But I appreciate any observations or feedback any of y’all might have.

.

4 responses to “A Few Sessions of D&D”

Oh yeah

This worth its own comment and string of responses: what/which D&D are we talking about?

Hi Ron, yes this is a

Hi Ron, yes this is a potentially interesting question. It’s actually 5e, the newest one. And not because I particularly liked it, but for two main practical reasons: (1) it is the easiest game to get players for – I tried to get enough people to play any number of other Indy games, but after months of trying I couldn’t get enough people together with compatible schedules to make them work. With the popularity of D&D, and the player/DM economy being what it is, I got enough players with the right logistics for a 5th edition campaign in just a few weeks. (2) the designers did make it easy (even expected) for DMs to incorporate house rules, although I’m sure they never anticipated as extensive a house-ruling as what I did 🙂 I expanded Inspiration points and replaced the XP system (they gave like 3 or 4 different XP systems in the game, interestingly).

I want to respond to your other thoughtful replies too, but it’s quite late for me and I’m fading, so I’ll try to get to them tomorrow 🙂

Bang-aramathon

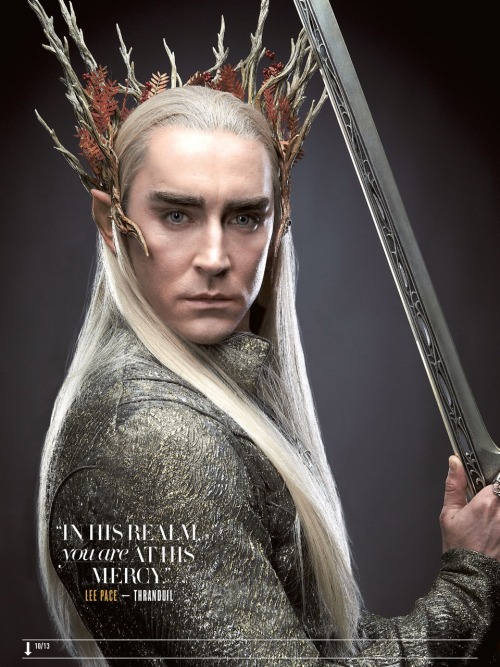

Adept Play is looking very elfy this week, between my character in the Legendary Lives game and this one. If someone would play and post about Elfs, then goodness, this could be the season for “elves do gaming,” or the reverse, across a pretty nice spread of genre and system.

I’m going to address something you mentioned first as a reply of its own, therefore this one begins with a more focused look at the single session.

Yeah, this is all about the Bangs, “bangin’ on the bongos like a chimpanzee” as the song goes, which is a good thing. The events you describe are relationships (father, personal background) or relevance to the bigger picture (elves as oppressors, medallions), all with their emergent opportunities and threats.

This is the time for a good point about Bangs (which I suspect is getting lost in some current discussions): that something emergent from play, like the consequences of killing One-Eye, is just as good a Bang as something that’s been prepped. In other words, Bangs are defined by content, not the process by which they’re created.

Nice Bangs: the undead plague + the knowledge of their not-dead friend being held captive, so that stuff is happening all at once across perfectly reasonable inter-connections. Coincidence is part of stories; it’s only contrivance insofar as anything in a story is, so it’s pretty much always “OK” to weave some in there. Contrary to popular belief, a given coincidence isn’t believable vs. unbelievable, but relevant vs. irrelevant. If it’s relevant, than audiences accept it not matter how absurd. Doing this is a big part of the job for whoever has authority over “and then what,” whether it’s one person throughout play or shifted around via the rules.

The father stuff is also very nice because, basically, the character sheet literally calls for it at some point. It’s helpful to think of it as a rule rather than some vague “story option,” i.e., when a character sheet (or equivalent) has X on it, then the “and then what” player must pull in X as soon as humanly possible given the point about relevance above. That’s another good Bang.

My point with the above two paragraphs is directed toward the many people in the past who’ve mistaken Story Now play for consensus-committee – in other words, they have said, “Oh, so any GM contribution is basically imposed, and therefore fiat.” I’m arguing otherwise, that authority of “and then what” is a great and wonderful thing, when it’s working with known components or components with some systemic presence (e.g. an encounter table). Bangs, Weaves, Crosses, et cetera, not to mention basically “prep,” are all about that kind of contribution.

What about the Tower of Records? Isn’t that fiat? I mean, it wasn’t there before, and now it is. My response is probably predictable: it was there, it’s built into the player’s sheet in every way to be here in this very location – where else would it be? (Uh oh. I’m risking the Socrates problem of posing snotty questions so I can swat them down – I’ll lay off that now.)

Let’s talk more about improv, especially the secret exit for the Tower as a feature of the next session. There’s a certain danger inherent in “if they try it, it’s there.” One must decide if this is or is not an operative rule for us (this game, our table, the way we do it). If you decide that it is, or that it isn’t, and stick to that, then all is good. If you hold that as a personal decision to be imposed in either way depending on how you want things to do (“it’s not tense enough, so no door,” “OK, they’ve suffered enough, here’s the door”), then the roll is now just for show and we’re back on the Gromit-built railroad.

Regarding the pressure you felt occasionally – let’s examine that. I suggest distinguishing between seeing whether they are entertained or not, vs. whether you are getting bored or not. Perhaps counter-intuitively, I suggest that the latter is a more functional play-device. You mentioned “spinning their wheels” or “started to get slow,” and I think that’s awesome: at that moment, you are the creative voice in a collective authorial head that says, “OK, enough,” and that is a very great and knowledgeable voice, whether in one head or many.

However, instead of interposing more “stuff” like dangers and whatnot, I suggest that a useful and non-leading technique is simply to cut. You can cut to something known that you think matters a lot, given what-all is happening, or you can cut to “OK, enough of that, it’s now happening [here; meaning somewhere their wheels would take them given what they were saying], and what do you do.”

So that way you’re not doing or adding “something extra” but merely focusing on what is really going on, heightening the relevance rather than risking drowning it in “more.” I distinguish sharply between the two, especially in light of the released plague, which is very much working with known elements and basically playing them as characters.

As I’ve mentioned before, “improv” as such is not the issue. There really is no difference between deciding beforehand to unleash the plague at some point vs. deciding to do it during play through inspiration of “I bet they’d do that now.” The question is whether the results of doing so are open-ended (a Bang) vs. nudge-y toward something they’re supposed to do or just for show as a fake threat to make the characters run faster.

Regarding the satisfaction relative to the Star Wars game: well, to be crude, you’re talking about a long-term relationship vs. a one-night stand. The latter’s comparatively here-to-do-it, in-it-to-win-it quality (“win” being mutual orgasm, not competition) is simpler and easier, given good will on all parts, as you had at that table. When it’s a long-term relationship, things develop at their own pace, certain things are investigated from different angles, and new phenomena may appear. Some things gain unexpected importance and others prove less important than expected.

I bet you’d be surprised at assessing the long-term players’ satisfaction – for example, it’s practically axiomatic for a Sorcerer GM to think that a given session or series of them has been a little flat, only to discover that the players are thrilled and blood-hungry at a sustained, almost scary level that cannot happen for a one-time session. Your observation about people changing their real-life schedules points to this effect, rather strongly in fact.

Fetch for me these thingamabobs three

Now I want to talk about the five medallions.

Roughly and perhaps too casually, I see three ways to interpret this. I’m pretty sure which one applies in your case, but I’m speaking generally. And maybe the breakdown is useful for you, let me know.

Way #1 is mainly directive: it’s the players’ job to stay on track about this goal, so the GM can always wave “medallion this way” at them for a session or location for a series of sessions, and they’ll point like pointer dogs and go that way. Anything else would be bad, uncooperative, “selfish” play. You can also assign downtime or side-story status to sessions because a medallion isn’t involved, like a “rest” or perhaps a power-up.

It works within a session too, in that you can always insert the medallion or a clue about it into things to spice up the situation and provide direction. The beggar seems like a scabby annoyance until he hisses, “But the medalllllion …” and keels over in a faint. Oh good, no more irrelevant debate about which to visit first, the wizard or the market, now we have something to do.

You can even self-deceive when doing this, saying, “Oh, but they always have a choice” when in practice they have no such thing.

Typically, in this case there’s not much real question whether they will or won’t succeed in getting them; the whole point is to experience the saga of getting them. Play as a whole would be a lot like reading The Belgariad.

Way #2 works differently, to establish chapters of play much like The Mountain Witch, e.g., the fifth medallion will have a climactic or finalizing quality simply because we know it’s the last one. Or maybe around the third one, enough information is now available to re-frame or contextualize the entire experience.

In this case there is no real or fake “will they or won’t they,” as the medallions are effectively an agreed-upon framing device, there for mutual enjoyment and not particularly compelling otherwise. They may become compelling within the fiction due to this-or-that good idea that’s associated with them, if present – and there doesn’t have to be if other good ideas are already adequate, e.g., character backgrounds or intrinsic features of individual scenarios.

The consequences in this case of getting or not getting the medallions would vary a lot by application. They could span the whole range from “the journey is what matters” to “disaster per failure, triumph per success” as far as the whole of play is concerned. It would depend on how they’re conceived and applied as components of the rules in play.

However, one could not say in this case that the point of play is to get them or to “see how we do” in trying to get them. They’re usually comparatively minor insofar as our interest in play is concerned, at least until some conflict about them develops that concerns other variables.

Way #3 is more challenge-based, insofar as succeeding or failing to get a medallion is treated as the collective goal and a tactical problem, given our resources, capabilities, and assessment of risks. In this case, we’d play until we either had them all, blown the chance for all, or had some by some specific end-point, and play through the consequences of those, with a final-battle context formed by how we’d done.

This way of doing it doesn’t have to be cold-blooded or creatively sterile. Other features of play like the captive father and so forth present their own subroutines of tactics, colorful and emotional to be sure, but they are generally assessed in the context of acquiring the current medallion. The same goes for ties and antipathies that may form across player-characters.

Given incomplete information about play, it can be hard to see the difference among these three. “In this session, they encountered a powerful barbarian tribe on the march, ruled by a sorceress. When they gained an audience with her, they saw she was wearing one of the medallions around her neck.” Which one is that? There’s no way to tell without asking more questions.

I do think there’s value in knowing what you’re doing with them, though. The temptations of #1 are real and very comfortable. One of my key points in this pair of posts is that our shared and extremely socially-reinforced notion of “story” as a transitive object passed from creator to audience is extraordinarily seductive in a lotus-eater fashion, as the necessary tension or in-the-moment authenticity demanded by a creative moment is simply absent. You can probably see that #2 and #3 correspond to Story Now and Step On Up, acknowledging incredible procedural diversity within each. Instead of #1 being the Right to Dream, as I may have conceived it in the past, today, I would simply call it betrayal of the medium and the unfortunate triumph of our training over the potential of doing this thing.