With great thanks to Petteri, Santiago, and Paul, we enjoyed diving pretty deep into the game, with more to go. Given four briefly-described choices from Petteri for our starting short-story piece, we used From the World of Old, which concerns a dragon who wakes into the developing civilized world (not really historical, but symbolic thereof) and decides to make his way there in human form. Our common proclivities may have turned it into some commentary on capitalism.

Here are our initial meeting video, linked here, and the play session, below. Since play includes a lot of writing and editing both personal and common sheets, it was beyond me to keep transcribing each version into images for the video, so I’ve attached a summary to this post. It might have some errors due to one or another fiddly point but you’ll be able to follow along.

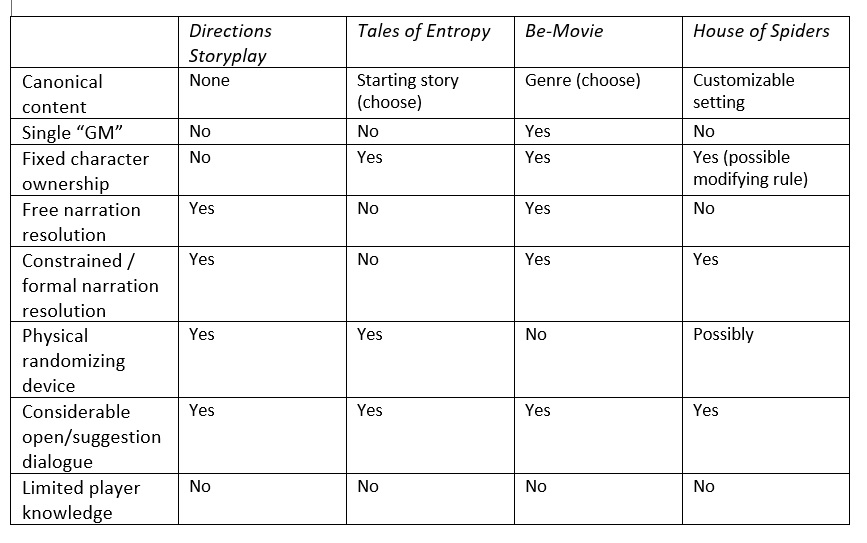

I’ve found it useful to keep the differences among four of the games I’m consulting for in mind, and already posted this table once, but it belongs here too.

Of all four, this is the most fixed-in-place for dice-based resolution, although not the most assertive regarding GMing.

The really-playing video’s a beast – even with pretty aggressive editing, there’s still almost two and a half hours. Part of it was due to perfectly ordinary learning, with how-to and what-is-that, but while editing, I realized that certain features of this multi-author play bleed into table-talk in a fashion that actually works against play. Or at least as it seems to me; perhaps that’s an individual issue. You can see me get testy about it as I am thinking, “all right, enough processing about what it’s like or how much it’s justified, what next for pity’s sake,” and then see me realize it’s not about me and just ride with it.

I’m bringing it up because this isn’t directly due to any techniques – the techniques being used shouldn’t take any more time or require any more dialogue than any other way to play. But something about the multiple-authority play tends to lead people to explain and justify more than otherwise.

Lest that sound overly critical of my play-partners, I’d like to signal that this is yet another instance, since the launch of Adept Play, of finding some really freaking nice and fun people to play with. Santiago was like a kid in a candy shop, busting out great ideas, and I draw your attention to his joy at realizing, “I can just play?” at one point.

You can see me get awfully confused about Flame, which I thought I understood, but then stumbled over – I hadn’t realized that you protected yourself from Folding by re-rolling; I’d thought those were separate and potentially opposed things. I need to review the rules to see if they confused me, or if I confused them.

I still have some system bones to pick with Petteri, which I think I’ll do as a consult and review here later. Briefly, they concern the amount of pre-baked conflict built in, as well as inadvertent story front-loading, and whether other mechanisms are easily used to counteract them, i.e., for them just to be available on paper may not be enough.

Another issue to consider is protagonism, or the possibility that the game turns the characters into unlikeable caricatures whom we’re all willing to make miserable, ownership or not.

Look forward to seeing the next session not too long from now!

18 responses to “Gold, dragon, golden dragon”

Of speed and techniques

Hi folks!

First of all I want to thank Ron for giving me this opportunity to examine both the communication of the game to the public as well as to the actual play experience. This has been most enlightening.

Regarding of the few issues. You mentioned that partly the reason for slow play was simply learning the thing. I feel this is correct, and I have to add the medium we are playing with gives its fair share as well. Entropy is quite a "forms-heavy" game, and as I haven't played it ever online it took some fiddling to do to get the processes rolling.

The online format affects the gameplay itself somewhat as well. As using skype and microphones tend to favor communication where one of the people is speaking and others listen, there are few places where this hinders the play a bit. Most notably when during a conflict the players who don't have a character in it negotiate how they will be changing the grains and in the same time the players who have characters in conflict decide what burden they are to give to each other. In gaming table this leads quickly to two simultaneous processes which only then report the end result to other members of the playing group, for them to continue with the narration.

Some of the conflict and scene procedures lend themselves to varying depths (and thus, speeds) of application.

During conflicts, when players apply traits, burdens, grains and shadow, there is a huge difference in how long players can explain their choices. Some explanation is always mandatory, but at the shortest it is just plainly stating that I use this trait, because of X and that's it.

Sometimes additional content in this phase gives a little more feedback into the fiction. During the play, I think Santiago once used this brilliantly, when he dictated that a being of the old world -burden hindered the dragon because a shot was fired in the marketplace (this was determined just before applying this) and the dragon was very unfamiliar with gunpowder devices. I feel that adding this kinds of bits to the fiction are a reason worth of spending a while over the phase.

Another place of varying depth is the voting for flame and shadow that occurs in the end of each scene. Here we adopted a quick method of assessing our votes and didn't discuss it that much. In the final conflict Ron brought into the discussion the nature of Marcus Llietti's shadow. I feel that sometimes a brief discussion of these matters can be fruitful (like Ron did in this example), if it doesn't slow the game too much.

Regarding of characters changing into caricatures. This happens if you conflict a lot. While the conflicting is supposed to be the main force driving the drama, not all scenes need to be conflict scnees. Conflicting between main characters is dangerous and corruptive. It has strong consequences that work through the whole game world, not only the characters involved.

We have now played two actual scenes in this game, and had two conflicts. There is yet to be seen the scenes that contain only one character and/or ones that have no conflict in them. These kinds of scenes affect the game mechanics in addition to bringing variance to the tension level in the story.

All in all, Entropy is quite free game in terms of players doing what they wish in actual play. It will take some time for the players to get accustomed to the mechanics and drive the thing.

Petteri

i apologize for the delayed

I apologize for the delayed reply. I'm dealing with off-screen time-consuming things right now, as we talked about.

In thinking about the table-talk, I'm factoring out both the learning curve and the screen medium. I'm familiar enough with both to think I can do that, and that what follows is looking specifically at something else.

Also, my observation isn't aimed specifically at Tales of Entropy and may not apply to it very strongly. Instead, I'm talking about the "family" of design that I've been addressing through several simultaneous consults. (By contrast, the topic of conflicts at the outset for Tales of Entropy needs more play and private consulting before discussing it here.)

So, this is a tough topic! After all, one of my main functional-play points throughout the past two decades has been to say, real-people talk is not the enemy. I think that certain baked-in habits derived from efficient demo/tournament "entertainment" play are not features of the medium. Talking only in character, being quiet when your character is not present in what's being played, restricting rules issues to immediate procedures and directing them only to the GM … that crap.

So the first point is that I am all for table-talk. Real people playing means that real people can communicate in ordinary language while they do it, as part of the medium itself.

That extends to talking about anything else; I think it's easy to distinguish between disconnected talk that distracts and detaches from the play-experience vs. talk about something outside of the immediate fiction which enhances the play-experience. It's not subtle – sometimes Monte Python references shatter and extract us, and sometimes they bring us in closer, and no one has trouble telling the difference.

In that case, what's my beef?

It's a matter of authority relative to the fiction of the moment. Broadly distributing and trading-off authorities, or responsibilities is perhaps the better word, around the table is a key feature of these designs. And that's also accompanied by opening up quick suggestions, reflections, reactions, and other contributions from everyone else.

Those are two different things. First, how the authorities/responsibilities are arranged and moved about, and second, how much talking about their use is taking place. In practice, and this may be a function of prior role-playing history or it may be a human social feature, these get confounded. It's easy to think that because the GM is not the same person from scene to scene, we get to confer more about what any given GM-of-the-moment is going to do.

My concern is therefore not table-talk. It is a specific application that transforms distributing and trading authority into blurring it.

Most table-talk is about something outside of play which is relevant to it in some way, or about what to do, i.e., what a character does, in procedural+fictional terms. When the table-talk turns to how person A wields authority/responsibility, that's … something else. Or it can become something else, a shift from a suggestion to the person who's deciding, into co-responsible committee work.

I have watched multiple sessions of Primetime Adventures, and read about dozens more, which tanked due to this phenomenon. One way is simply unplayable mess, which is easy to see. The other way is subtler and to my way of thinking more dangerous – the group accepts that every single thing anyone says is subject to consensus-based committee discussion, and play itself becomes a very thin thread meandering through the clotted mass of talking about what it's supposed to do, moment by moment.

These circumstances also open the way for the agonizing problem of so-called freeform play, meaning that behaviors can get pushier and pushier even when they're polite and helpful and "just suggesting." I've seen PTA play in particular turn into the most egregious improv-railroading of the purest 1990s form, in which the person who took over would be shocked, shocked at the suggestion that they were doing it.

Again, I'm definitely not pointing at Tales of Entropy as facilitating this problem. Of all the games I'm consulting for at the moment, it's probably the least potentially likely to fall into this trap at the table. But it is a problem for this zone of game design, due to confounding those two things I tried to separate above.

Narrating, GMing

Since you and Ron are taking about it, Petteri, I’d like to ask a rules question. I would get it if it were a situation of rotating GMs. But I’m a bit confused because, it seems, the only scenes you can narrate are the ones where your character appears. (Or is it that way because we were taking turns narrating in the order of our characters?) I can’t fathom having traditional GM privileges and controlling a PC at the same time.

Relatedly, you’ve said that it’s not mandatory to put into every scene a conflict between player characters. What else could happen in a scene? Conflict with NPCs? No conflicts? Either?

Aaaaagghhh.

Aaaaagghhh.

“and the only way that another PC may be in the scene is if both its player and the Narrator agree”

****SUCCESS****

Rules clarifications

I was watching our fun from the video and few things came up that probably need a bit clarification. Also the questions Santiago presented, I will answer them in the end of this post.

Operator/Narrator distinction. These terms mixed a lot and perhaps it is because the words resemble each other as well. I wonder, Paul might have suggested this to me earlier to change one of them. In any case, Operator is the one who knows the rules, reads the beginning narration. I am the operator in our game. On the other hand, Narrator is the one who is setting the scene and has rule over disputes over that scene unless they are handled through conflict mechanics. The role of Narrator goes around the table.

The using of Flame to stop a character from Folding. This got somehow mixed up in some of our discussions. The rule is: with one point of flame, you can re-roll any of the dice that is in your pile, be it one die, five dice or all of your dice if you prefer. The usual tactic to increase your result is to re-roll your failures (1s, 2s and 3s) and a more conservative roll, just trying to reduce number of rolled 1s is just to reroll them. This is the only mechanic that Flame can be used inside a conflict. But this absolutely means that using Flame prevents a character from folding, because if you roll for example three 1s, the only way for you to prevent your character from folding is to use a point of flame and reroll those 1s.

Flame has two additional usages:

With a point, you can preserve a grain from being tampered with inside a conflict.

With a point of flame, you can heal some (or all, depending on roll of the dice) of your burdens. This needs a scene that validates this in fiction and is usually done only few times during a game.

That being said, Flame points are very, very valuable in conflict itself. If you, for example spend two points in a single conflict, you probably will boost your result quite a bit, if you have a large dice pool to work with.

Then Santiago's questions about narration and character involvement:

The role of the narrator goes around the table in clockwise order. Character involvment in the scene is dictated by the following rule: A scene must contain at least the character that has the least amount of scenes played. This can easily lead to a situation, where narrator won't narrate to his own character, although in our game we only had two scenes so we haven't seen this yet.

When you do narrate to your own character, it is usually a good time to drive his goals forward or to reveal something new of your character. In previous case you'll usually end up in a conflict with another character. In the case of the latter you might have a scene where your character is the only character involved in the scene. It might have a conflict against the game world (npcs, or just trying to have some lasting and changing impact on the world. It might also not have a conflict at all.

The first scene we played is a good example of this. When I stated that Scthylia is trying to gather ha horde of people to go with him from the market, I stated that now is the time for other characters to intervene is you wish. Paul took up the challenge, but if he hadn't, I would have formed a conflict against the game world. When conflicting against the world, the player of the winning character can make the change to grains instead of players who do not have a character in the conflict. I would have then poured my victory to a grain "Dragon's horde of people" or something like that.

So, I guess this answers to Santiago's second question: no, there doesn't need to be a character-character conflict in every scene. I have found out that especially if the characters have lots of underlying issues and things that need expanding and revealing, calm scenes without conflict really enhance the experience. Also few rules usually come up in such scenes, the healing mentioned above in the using of flame. Also, player might wish to change character's traits to react something that happened in fiction. Usually this is caused by a revelation of some sort and a calm scene is just the spot for it to happen.

Very helpful! I think I’m

Very helpful! I think I'm responsible for being both confused and confusing about Flame. I thought that you increased your total points by spending Flame to re-roll (which is true), but avoided Folding by not doing that too much, so you had Flame "in reserve" that was used to keep from Folding in some way as a final step in the conflict.

That's why my diagram has two separate statements for the Flame arrow, when it should have just one. I'm revising it now to reflect the actual process.

I've checked the rules, which are completely clear, so there's no one to blame but myself.

Thanks a lot! Then I have

Thanks a lot! Then I have more questions. Suppose I’m the Narrator:

1) When I narrate the scene and include the character that’s appeared the least… ¿Can I include other player characters as I wish? ¿Or do I have to ask permission to their players?

2) How much can I narrate, regarding a scene with only my character, without going into a conflict? Suppose I narrated Llietti going to a government building and asking for a declaration that he be the only licensed apple merchant or whatever. How do I know when can I have the NPCs say “yes” and when do I need a roll?

3) The only way for me to narrate a scene with only my character is if it’s my turn to narrate and my character’s the one that’s appeared the least, without tying with other characters?

4) When can I spend a point of flame in healing my Burdens?

Thanks a lot! I’m really liking this system

(oh, number 4 wasn’t related

(oh, number 4 wasn’t related to me being the Narrator, sorry)

Some more answers

Great questions, here are some answers:

1) It depends. Sometimes it is obvious from a fictional standpoint that a character is either in or out of the scene. For example, if Paul's character now is willing to interrogate Scthylia, it is obvious that my character is present, as he was taken into custody when we last saw him. But if it is not obvious in fictional standpoint, the narrator and the character's player decide it together. If both agree, then a character can be involved in the scene. If, for example you would argue that you wish Llietti to be involved in the interrogation scene, this feels to me pretty far fetched, but it is up to Paul's judgement as he is the narrator. On the other hand if you feel that your character shouldn't be there, Paul couldn't drag him into the scene even if he wanted. So I guess I am saying that we are searching a reasonable combination of characters from fictional standpoint, but if players do not find the common ground then there are clearly cut rules who decides how it goes. Regardless of this all, the character who has least amount of scenes played is going to be involved, the scene is built around him.

2) This is again, an interesting question. The simple answer is, you can narrate as much as you wish, taking into consideration that no matter how much you narrate, you can't take the other player characters out of the game without setting a conflict against them. An extravagant example: You could narrate that the people vote Llietti for a new dictator of the town. No matter, there are still Scthylia, Arcturus and Zocchi there and they can (and will) mess Llietti's future whether he is a master merchant or a dictator. The goal for the narrator is to create interesting fiction that shows the characters in interesting situations. It is up to the narrator's taste, how lavish or extreme things he wishes to narrate.

If you wish to get something that has power besides the narration, having elements that affect dice rolls then you need a conflict. Above example: you could narrate that Llietti runs for dictator in town and have a conflict of it against the game world. If you win, you can create a grain "All hail dictator Llietti", or something. This creates a mechanical leverage that exists in the future conflicts until it is destroyed.

3) No, you could narrate a scene for, say, Paul's charater if he has the least amount of scenes and you can dictate together that he is the only character involved.

4) This is restricted to a scene that has a recuperative, or transcending aspect in fiction. Just off the top of my hat, Llietti could, for example, meet a poor street beggar who touches his heart, forcing him to rethink his life and thus "cleansing" him from inside. Healing is not just spending flame to improve your character's effectiveness, but it should mark a definitive moment of your character's life in the story …. it resembles a new direction he is taking. Usually after such an event, the following burdens your character has are somewhat different than the ones you got earlier, especially if your healing roll succeeds very well and manages to remove many of your burdens.

Speaking of burdens, Ron mentioned earlier that there is a risk of players purposefully taking the characters down and dragging them in the mud with burden. This varies a bit, but often the type of burden characters get is linked to the way the player portraits the character. There is a clear example of which kind of burdens we gave in our previous game: Llietti, Zocchi and Arcturus got quite nasty burdens, because your characters feel mean and shady in many ways. Surprisingly, the dragon, which is not a boy scout in any means took almost the role of a "good guy" and it can be noticed from the burden Paul gave him: "Targeted by the slavers". This is a tendency with this game, the good guys get quirks, situational hazards, wounds, affections and such where bad guys tend to fall deeper into their own psychological rabbit-holes with vices piling up.

Thanks a lot.

Thanks a lot.

Well, I wouldn’t say my character’s looking like a bad guy and yours like a good guy… But that can certainly be your opinion, haha.

Let me do follow ups.

1) Not a question, just restating it succintly for myself: When the Narrator starts a scene, she must include the “least appeared” character, she can include her own character, and the only way that another PC may be in the is of both its player and the Narrator agree. (I said this wasn’t a question, but do correct me if I’m wrong, ha.)

2) Interesting! So I can choose to turn something into a conflict to have its consequences “hard coded”. But let’s say I play it safe. No, let’s say Ron plays it safe and narrates Zocchi being named Pope of Scthylia. And I, Santiago, want to stop that from happening. Not having my character react after the fact, actually preventing it from happening in the fiction. Is there anything I can do?

3) Oh no, I mean, when can I narrate a scene with only my character. At which points in the game. I’m understanding it’s only if my character’s the one that’s appeared the least, and only if he’s the only one.

4) Similarly, I meant to ask when can I spend a point of flame to clean my character of burdens. Does my character need to be in a scene? (I understand the answer is yes.) Do I need to narrate the scene myself? (I understand the answer is no.) Does my character need to be alone in the scene? Do I need to wait until the turn order and other features of the system give me an opportunity to do it? (Meaning, waiting for my turn to narrate or asking during someone else’s. The opposite would be if you meant that those most “cleansing” scenes can happen out of order, like a parentheses.)

Meant to write: “and the only

Meant to write: “and the only way that another PC may be in the is of both its player and the Narrator agree”. My cellphone betrayed me.

Aaaaagghhh.

Aaaaagghhh.

“and the only way that another PC may be in the scene is if both its player and the Narrator agree”

****SUCCESS****

1) You are correct. I just

1) You are correct. I just add the fact that sometimes fiction dictates that a certain character is in the scene as well as the one especially chosen for it.

2) Not really. Entropy is a game that places a lot of power and with it, trust to all of the players involved. You could state of your opinion of the matter but as it is Ron's turn to narrate, you really have no power over it. The only "hard-coded" limits are, that you can't crack other player characters through narration only. Oh, I forgot to mention that if there are very definitive grains in the play. Lets say "Pope Francis" is in there, and Ron wishes Zocchi to be the new pope, this would require a conflict against the world. Perhaps Zocchi has him assasinated or something to get to the position himself or something, anyway changing grains require a conflict to commence.

3) Tying doesn't restrict you here. If two characters are tied, then it is the narrator's option to choose one of them as the "main" character for the scene. Others can then join as discussed previously, but the requirement is always for one character only. This is simply due to demands in fiction. Lets say that Llietti and Scthylia have both had the fewest amount of scenes and it is Ron's turn to narrate. Our characters happen to be in totally different directions and there are no clear narrative rationalizations to put them both in the same scene. This is where Ron picks either of them, and narrates.

4) Burdens-cleansing: your character needs to be in the scene. You do not need to narrate the scene yourself. Your character doesn't need to be alone in the scene. As stated, you do not need to narrate the scene yourself, so you need not to wait your turn to narrate. The cleansing-scenes are normal scenes in regarding of scene order. It is not a free-from-jail card also, as you spend a point of flame (extremely valuable), roll dice equal to the sum of your burdens and leave it on the hands of fate: you might heal all your burdens or not at all, but still you lose the flame-point you spent. The roll is always made before the actual narration of the "cleansing", because it might have a great impact on the scene itself. For the example I gave earlier about Llietti and the street beggar, the details of the scene might vary drastically if Llietti is healed one point of burden to that when he heals all of his burdens. One might vote shadow for him, if he doesn't heal even though the street beggar would soften any normal human being :).

Thanks a lot! I hope I’m not

Thanks a lot! I hope I’m not being too bothersome. Regarding 2), now I want to ask you who decides there’s a conflict with one of the grains. I’m thinking that if I didn’t want Ron’s character to become Pope, perhaps I could say “We have all these grains related to commerce, the merchants and other people don’t want religion to become important, make a roll against those grains”.

I promess this is not at all theoretical, it’s all related to stuff I want to have Llietti do on the next session!

No problem, I am happy to

No problem, I am happy to answer questions about the game.

There are two ways to initiate a conflict against the game world:

1) Player of the character purposefully "attacks" against the grains to make a change in them. Example of this would be the one I presented earlier with dragon trying to get the mob.

2) Narrator initiates a conflict for the character as he feels the character must overcome the world or submit to its power (grains). The example you just gave falls into this category. However this is a narrator's privilege, so if you are not the narrator and not the player whose character is involved you can only discuss and suggest it, not demand.

Ooooohhhh I see now. Thanks.

Ooooohhhh I see now. Thanks.

Wait. When narrating, am I constrained by “scene” in the sense of unity of time and space? Suppose that in my next turn I narrate this:

“Llietti wakes up with hangover the following day, and without having breakfast he goes to the city hall. He threatens the current mayor to come down on his debts; arranges to forgive the mayor’s debts if he gets a chair on the Civic Council. The mayor agrees. Then, he goes to the market and buys all the slaves. All of them. The next day, on an emergency Council meeting, he passes a law calling for an emergency election. The next day he frees his slaves, they all vote for him and elect him City President.”

(I know it sounds fun but it’s not really what I think I’ll do, so I hope I can “waste” that material here without hindering our game. Fingers crossed.)

Would that be acceptable as a narration? (Supposing I annex the Least Played Character at the end and ask its player “What do you do”.)

Scene is not just a time and

Scene is not just a time and a place. The best analogue for me is to think about a scene in a movie or in a play. Not only it has a certain time and a place, but also a theme and cast of characters that are involved.

In your example you are the narrator and the least played character is not yours, right? If so, your narration is not really valid, as the scene is supposed to be built around the character chosen for the scene. The scene is built around your character and not the one that it is supposed to (the least played one).

If, on the other hand, you are narrating for your own character, then it is legal. However, in my taste I feel that you are cramming up too much things into one scene. It has much more dramatic impact if you would, say, spread those things you mentioned in three different scenes. With conflicting against the game world you could achieve some game mechanics impact and perhaps some of the other characters would intervene in some point of your rise to power. But your mileage may vary.

Ooooooohhh. Ooooooohhh, I get

Ooooooohhh. Ooooooohhh, I get it now! I have to construct the scene around the other character, then. This is fascinating. Thanks a lot, Petteri.

As for the somewhat edge case that I narrate a scene when my character’s the Least Played, just when I want him to become powerful in the world… We’ll see if it happens in play. At the moment, it seems like a matter of tastes, and socially enforced stuff, not rules.