Sometimes people email me with questions. Since I don’t know them, and don’t know the (sometimes) complicated process that led to them deciding to ask, I have to ask dense-seeming questions back in order to know what they’re talking about before I can answer anything, or know if I can answer at all. In this case, the person was very clear: first, upon asking how many hexes does a character move in a round (or go, or turn, or whatever), and if it’s baesd on the physical score, Stamina; and second, explaining that their prior play-experience with five or six titles was all hex-map based.

That led me to dig out some useful historical titles for this topic, because Sorcerer stands foursquare within a particular long-standing method for it. I was not sure if a simple two-sentence answer would make sense to someone who’d always played with a hex map and movement allowances, and didn’t want my explanation of Sorcerer to imply that it was weird or modern or unique. The result was a nice little presentation that I think might prompt more discussion – so comment as needed and as you please!

8 responses to “Movement and maps”

Thanks for bringing this up!

This is a subject I'm incredibly interested in because it's something I've been struggling with (probably agonizing over would be the better choice of word here) for a while in my own design works.

I need to preface this with an apology, as english isn't my native language and this will probably a lot more baroque and verbose than it needs to be.

On to the subject, I strongly appreciated the overview on the RQ/GURPS/CoC family of games and the analysis on how they marry a very detailed combat engine (at least in terms of describing in minute details the process of hurting each other) with very abstract, TotM oriented movement and positioning.

I also appreciate the explanations on how Sorcerer handles the subject because it is one of my inspirations for what I'm working on and while I'm probably going to land fairly far from that approach, it was instrumental in understanding what I wanted from my design.

The first observation I can share on the subject (and I'm sure it's far from uncharted territory) is that my impression is that abstraction is a good friend of fiction. Aside from the obvious benefits of using a TotM approach to positioning and movement when designing fiction-first game mechanics, I think there's a strong psychological element here that helps players stay in the fiction: having to imagine things because you can't visualize them on a discreet, checkered piece of synthetic cloth covered in miniatures requires you to constantly stay in the shared imaginary space, to ask for details, to populate it (which also encourages mechanics that allow you to do so). Plenty of games do this very successfully in their own way.

Now, my problem mostly comes that the game I'm working on kind of doesn't belong to that family, nor to a more narrative oriented one. It would be too long and uninteresting to explain, but suffice to say that once combat begins, the purpose the design encourages is definitely oriented toward a "Step On Up" experience. The whole premise is creating a very simmetric situation where the creatures controlled by the Narrator and the player characters go at each other with every player actively trying to "win" the combat. The Narrator's job is trying to provide the fairest but most determinated challenge possible, and the players' job is to overcome it.

Now in order to do so, the first problem is that our design is by intention and necessity one where we cannot really let the fiction lead the action; we have players picking abilities from lists and we have a strong degree of tactical maneuvering. Fiction is very important in the design – I like to think we have come up with a functional example of "IIEE with teeth", but I'm not qualified to make that claim for sure. I like to mockingly call what I came up with as "fiction-in-the-middle", but it definitely doesn't qualify as fiction-first.

The second observation is actually not really tied to our design and possibly more universal: once you encourage that kind of purpose, once you ask players to give their best to overcome a challenge presented by a player that by necessity has a wider array of options at his disposal, you need to first equip them with the tools to do so, but also with the informations that are required in order to make an informed choice on how to use those tools.

Here is where, in my opinion, using a TotM approach becomes dangerous, and where my difficulties arise. Unless you create a system that regulates "how you get where you want to do what you want to do" in a way that is abstract but fair and accessible to all players (here's where Sorcerer's solution comes to mind), you risk making players unable to make meaningful decisions (usually by making those decisions not particularly meaningfull). Using grids and hexes obviously solves the problem, with a steep price: it defangs the fiction by turning combat in a very mechanical act (where you can make incredibly satisfying choices such a perfectly placing a line attack or a push effect to obtain the maximum effect, but again at the price of a greater transparency of the mechanics that underly the fiction).

We didn't want this, but we wanted the detail, and the process of finding a solution was very painful (and not yet successfull, in my opinion). The additional problem is that we're already using the tracking of time as a tool (we don't have a traditional turn based setup, but rather a "I want to do this, and this takes so much to accomplice" system), which makes tracking space an additional burden. It works well enough, in fact it does in a way that's very in the in-and-now rather than being a bunch of numbers on your sheet, but I'm not sure it's easy.

And then there's the wholly different issue of how grid/hex based combat tends to make things that should be dynamic… static. I like to think at movement in a combat situation as a state rather than an action – going from here to there is fun enough, but once you're engaged with your opponent all of that gets thrown out of the window because mechanics don't really incentivize people to move around. It's the usual Erroll Flynn movie comparison: in an actual duel opponents cover a lot of ground as they press each other, push and pull, dodge, retreat and so on (in Phantom Menace the last duel takes place in at least 3 different, huge environments without the combatants ever disengaging). Games that use grids do a terrible job modeling this (one could say TotM do nothing to model this, but I'd rather say they generally do nothing to antagonize this, and that's good enough), which again I find frustrating. That's why I say that I think how I move is a more interesting fictional element than where I move.

Ok, this has been too long already and I'm not really sure I've said actually anything interesting. I'll be grateful for any sort of feedback or insight. In the mean time I'll keep banging my head on my desk.

It’s an amazing and excellent

It's an amazing and excellent comment! I apologize for not replying immediately, but I hope to provide a good one as soon as I can. A lot of my recent, pretty extensive game of D&D4E involved finding the dynamism in its grid-based combat.

Thanks!

Thanks!

Take your time, it's not like I'm going anywhere with this at the moment, sadly.

Hi! Let’s start with the last

Hi! Let’s start with the last point first: the static qualities of grid/hex in role-playing. I am familiar with this point, but I think it’s misplaced. My view is that the “static” feel more often emerges from the order/action procedure, what I call IIEE as you know, than from the presence or absence of physical representation. If that procedure relies on a fixed turn-taking order with everyone else essentially frozen during play, you get a sequence of freeze-frames in which one person at a time is empowered to move and do things. At the risk of going down a rabbit hole, one reason I mentioned D&D4E earlier was because it includes considerable actions and movement effects by lots of characters when it’s not their turn to go, which makes for a much more engaged situation – you don’t feel “trapped” in your square just because it’s not your turn, and often your precise movement or target for your “sudden” action is up to you.

But you are talking about not using a grid of any kind, rather than ways to make using one fun. Good enough, let’s proceed by accepting (and enjoying) that in such a system “how vs. where” should get our attention. The point you make about abstraction is fine, although I suggest we don’t need to find special reasons to justify or explain or feel like we have to make a case for doing it this way in comparison with the grid/hex techniques.

So, doing it this way – as we go along, basic information is available, and everyone fills in as they see it, and if there’s a need for our fill-ins to be consistent, then we have an authority to orient or consult when necessary. That’s a big deal. Someone has to have a rubber-stamp about where things are and what they may be, or be like, with the proviso (for the game you’re talking about) that such rulings cannot play a tactical role as one of their particular characters’ advantages. Such a ruling has to constrain the speaker, going forward, as much as it constrains the person who needs to know. And that leads to the other big deal, that this same someone has pre-determined hard constraints already, and has been obeying them all along just as if they were “anyone else.”

For example, there’s a square lava pit in the center of the floor of this square room. We got it. From now on, my guys and your guys must all take the consequences if some aspect of the movement or impact rules pitches one of’em in there. I don’t get a pass because I made that terrain up in the first place. So, similarly, in some kind of ruling about whether the rafters hold up as you brachiate across them above the lava pit … well then, I don’t get to say suddenly that they’re too flimsy for that and give out just as you’re over its center. I have to stick with the fundamentals, which if you go back, says that this room is basically sound and whole, not full of flimsy stuff, and its only drawback (danger) is the lava pit.

You may be interested to know that I consider the fiction-first/mechanics-first debate to be a lot of stinky bullshit. We don’t need to take that into account or to invoke one or the other (imaginary) side in order to discuss your topic. I do understand that you’re saying you don’t want to arrive at what’s in the fiction in some airy-fairy way that obviously allows one-sided advantage in what’s supposed to be a play-hard hit-hard combat experience.

All this is to say, then, that I don’t think theater-of-the-mind presents the kind of instability or one-sided advantage that you suggest it does. I think the sources of instability and one-sided advantage are the same whether you’re using a map (hex, grids, movement units) or not. And the solutions to avoid those problems, which as you say are very important not to have for your game, are pretty clear. Get a good IIEE, get a lot of responsivity in there, but limit it, and include options-limiting consequences to resolutions. In other words, you need Bounce. To use this system, GM and players alike experience Bounce in using the mechanics, which means you cannot predict just how things are going to turn out, moment by moment, and furthermore – crucially! – the Bounce itself is framed in understandable, accepted fictional terms, so it’s not merely an artifact of the dice or whatever causes it.

Terrain and various objects in it are sources of Bounce, or there’s no reason for them. Stuff’s in the way, it can get hefted, that thing is way over there, this one’s right here, and some of these things can really hurt you. Consequences for failed or not-fast-enough movement means encounters with the terrain.

The way it provides Bounce … well, there are thousands. You can treat them effectively as agents, “hazards” which by the mechanics are attacking the characters. You can treat them as specialized/localized consequences for failing to do something properly whether by the dice or by decision. They can operate as constraints upon action and as opportunities for action, i.e., as framing devices for announcing what you do. Those last three sentences aren’t a romantic litany of “all they can do” at once – instead, they are very distinct mechanically-situated options which should not operate all at once. A given system uses one of them as its means for terrain to operate, for lack of a better word, coherently with the rest of the procedures.

Again: I think these points are solid and the same regardless of whether you have a fixed-unit map. Such a map may play a positive role in how the specific procedures work, and in some other game, not having a map may play a positive role in how other specific procedures work. Not having a map with the first procedures would screw things up, and having one with the second procedures would screw things up.

But I think you should put aside this notion that theater-of-the-mind is non-tactical and vague or fiction-first, and somehow not suited to tactical, determinate, and hard-played combat. I submit that Sorcerer’s solution is not abstract, but instead rooted in the hard constraints of sacrificing your action to defend or not, and also the opportunities of rolled-over victories from the prior role. With those in hot use, the role of terrain becomes a handmaiden, or assistant, to what is less or more possible, and narrating it as such has a nice way of hardening or refining everyone’s understanding and use of it as the situation plays out. In other words, if the other mechanics force things like terrain and objects to obey, then once they’ve obeyed, now that they’ve seen use, they are now effectively in place (where they ended up) just as “hard” as if you’d drawn them onto a map. And the roll to see if you can get to one of them before the other guy is just as mechanical as any movement rate across a grid – it’s just a different kind of mechanic, neither more abstract nor more representative.

That’s what you need: good Bounce, and a solid shared understanding of how terrain factors into it – roughly put, “going in” as a fore-known constraint, or “coming out” as a consequence of a resolution that was constrained in some other way. This way the tactical decisions can remain meaningful and the situation’s terrain makes perfect sense as we go along.

I’ll spitball a thought: let’s say we have a great combat resolution procedure that really captures differences in personal skill and also has a lot of potential to punch home, but you never quite know when (i.e. it’s not a “health bar”). And you don’t want that grid – never mind why, or all that stuff about fiction and static, it’s just because. You know what I’d enjoy? An independent “gotcha” die that gets rolled alongside the resolution, representing this particular terrain’s potential to fuck up whatever else is going on. Terrain is rated from pretty favorable to absolutely catastrophic, maybe that’s just a little die to a big one, whatever. Maybe it gets bigger for the moments you use certain actions. Its purpose is to determine whether, this time, right here in this spot, the terrain messed you up. You don’t know when. It might not ever catch you; it’s a die, after all. It might have some “advantage-y” nuance, I don’t know, I’m trying to keep this simple rather than a whole huge table or something.

See how that works? No map, no GM inventing tables for his guy to leap on and not for you, no yip-yap about what “would” be there or what “wouldn’t happen.” But tons of tactical concerns, and understandable intrusions of terrain just as you might experience yourself.

I’m not offering this as the solution to all your cares, but rather as an example of a quickie way to get the tactical and iffy features of varying terrain into a fight, both without a map and without the various worries you raised about not using a map.

Wow, that’s a quite

Wow, that's a quite comprehensive answer, there's a lot to unpack for me.

I'll preface by saying that I completely agree on the point on D&D4E: it's my favourite version of the game and it's fundamentally my gold standard for grid-based tactical combat situations. You raise an excellent point on how the variety of forced/compulsory movements and movement-based reactions make the game feel much more alive and dynamic experience; there would be a whole lot here to discuss but I do feel like the 4E solution, while maybe not perfect (but what is, really?) is absolutely enjoyable for me.

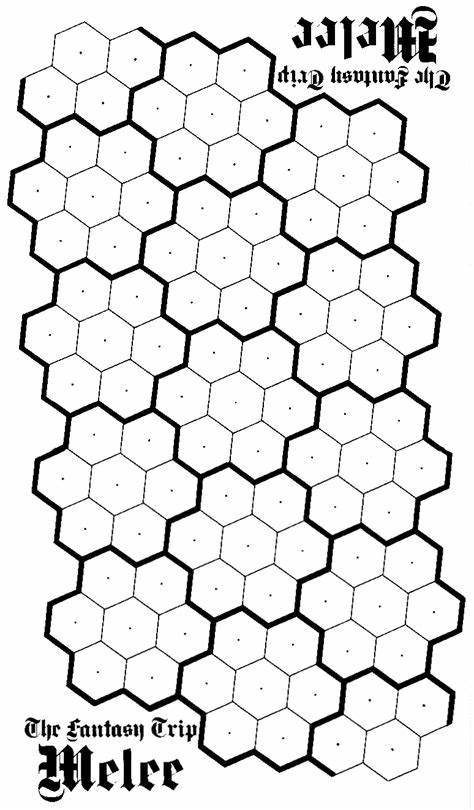

Moving from there… I fear I wasn't very clear in my exposition, because we do are using a grid right now (actually, we're using hexes for a set of reasons, but still, it's the same). I have zero objections on the utility and enjoyability of grid based systems – probably my only real issue is that using grids and map creates a very distinct "we're now moving into combat mode" moment that has a powerful effect on the flow of the game. I guess it's some relic of the "the game must able to handle every situation" mentality we grew up with, but the thing I dislike the most in games with a very strong tactical combat component is that it makes it hard to handle situations like James Bond quickly eliminating a set of guards without really needing to drag things through a battlemat. Which is silly, ultimately, because no roleplaying game is equally suited to recreating every type of fiction, but eh, I guess it's harder to let go when you're writing the game and not playing it.

Now on to the real meat of the discussion – first, appreciate your position on the fiction-first discussion. I also feel it's a fairly artificial distinction but it's still incredibly prevalent in discourse (at least among my fellow countrymen, apparently). Having that out of the way is a relief.

On the rest, well, hard to disagree with anything. Bounce is a perfectly functional solution for introducing those aspects in a very symmetrical, system driven way. I've been thinking about the possibilities while driving this morning and now I have a fairly long list of things I want to test because they could be the answer to something I wanted to do but didn't really fall in place for now. I shall thank you, because if this idea lands anywhere good it will probably make the game a whole lot more enjoyable. And I guess you're right on how using Bounce for these mechanics is appliable to both fixed-grid and TotM – in fact, right now I see even more possibilities in applications to our grid-based solution.

I also feel my use of the word "abstract" has probably been less than proper; I was more or less circling around the notion that it's hard to replicate a certain type of "tactical engagement" without having a fixed unit grid. The "I'm going to place my AoE attack here so that I get 2 guys and then move in this corner because I can move 7 squares and this gets me out of the way of the other 2 goblins". Of course it's not the only way to create tactical engagement, but it's one way that I find very hard to replicate in a TotM environment (even when using solutions such as range bands and such). I guess it's the very specific kick you get from having to compromise your position and your attack and ultimately "gambling" on one solution being better than the other. Which is something that your suggested solution could absolutely replicate, in a different flavour.

Lastly (sorry, this was an even more incoherent answer than the first) I'd like to touch on two things you mentioned in the light of what I'm working on.

The mention of having a solid IIEE process comforts me because that aspect is the single element I'm currently most proud of in our project, and it becomes the stepping stone on which everything is built upon. For example, the ideas I'm having due to your suggest on how to implement Bounce are really easy to implement because of how the IIEE process is handled by running a sort of "dialogue" between narrative authorities, and it can beautifully fall into place (the player who creates the difficulty for the acting character naturally sets up the opportunities for the acting character to accept Bounce in order to overcome it).

The second thing is related to that "gotcha" dice solution you suggested. While not immediately the same thing, we do have an "hazard" die mechanic – in short it's a 10 sided die that rests in the middle of the table and gets turned to an higher and higher value as different things happen and the situation becomes more tense and dangerous. It's basically something that ensures that fights are climaxes, because it's generally something that benefits monsters (say that the Dragon can only really use a certain ability if the "danger meter" is on 5 or more). But players can benefit from it and game it because some abilities may allow them to reduce the value ("tank-y" characters are really good at defusing situations and keeping the danger meter in check) or even use it at their advantage (and using the dice always reduces the value, whoever uses it, monsters or players).

It would be fairly easy, I think, to bring terrain and hazards into this in a variant of what you suggest. Certain actions could carry an element of risk (moving over damaged planking while fighting a troll may trigger a collapse if the danger meter is higher than X, or taking a shortcut over a recharging geyser may increase the danger meter by Y, I'm just going wild now).

Ok, I got myself an headache.

Thanks for the insightful response, it has been really useful.

It’s a fun discussion. I’m

It's a fun discussion. I'm thinking maybe we should take it to an Actual Play post of your own rather than a sideline to this one.

As an enjoyable look at older posts here about 4E, try The Abomination That Shall Indeed Be Named, and the posts in Actual Play from late 2017 through spring 2018.

Sounds good, but how should I

Sounds good, but how should I frame the discussion? Around 4E actual plays, or examples from my own game?

Um, one of each, or both

Um, one of each, or both together if that seems good for the topic, or one of them, depending on what you'd like to talk about specifically. If you don't mind an observation, you do seem willing to chat up your own game, so it seems only right to show it off in a post dedicated to that purpose (in addition to brilliant topics discourse et cetera).