I’m teaching a 400-level undergraduate course called “Environmental Communication” this semester for a handful of students in my campus’s Environmental Studies program; it’s intended as a writing seminar. I meet with them once a week for two and a half hours on a Monday evening, although it usually winds up being much less than that. With one exception, they’re not really writers, and if I’m honest, I’m not really cut out to be a writing teacher.

But they enjoy it when we play games! We’ve played a game called Exquisite Biome (available via itch.io) and a tragedy-of-the-commons board game called Kyoto. Those were quite engaging.

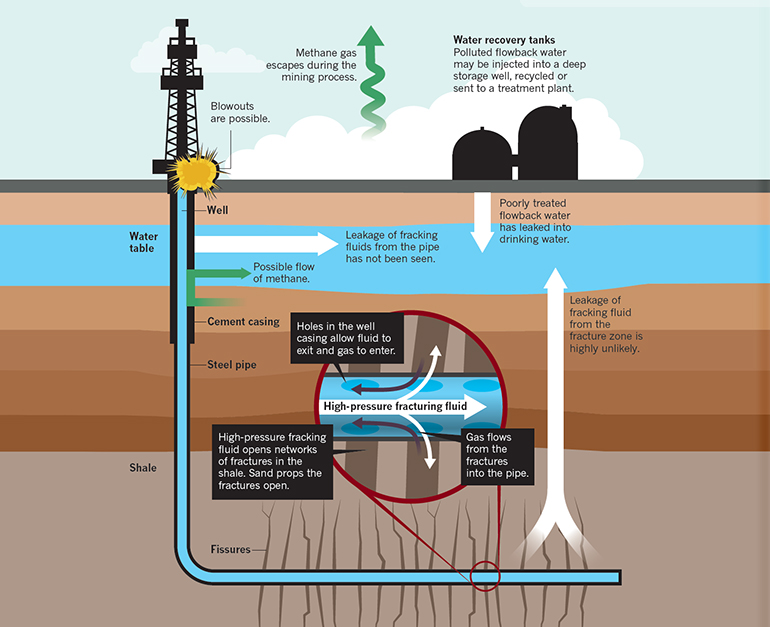

On Monday, we played Amerika using the version available to supporters of The Happening. A few weeks ago, I showed them the game and asked them for ideas about an environmental injustice to be the focus of the game. They agreed on fracking, which is “high-volume horizontal hydraulic fracturing.” This is a means of extracting natural gas. It involves drilling deep wells to punch through the rock layers covering layers of gas-bearing shale and then planting explosive charges in the shale layer to break up the rock and release the gas bound up in it. This can then be extracted by high-pressure fluids. The process employs highly toxic and carcinogenic chemicals that can contaminate groundwater, and the shattering of the shale layers may produce sinkholes, earthquakes, and other geological instabilities. It also uses up large quantities of fresh water on an ongoing basis, contaminating them irremediably. Given the fact that the campus (and, indeed, most of Pennsylvania, the U.S. state it’s located in) is situated atop the Marcellus Shale, a natural-gas bearing geological formation suitable for fracking, it seemed like a legit choice.

I created a handout describing some of the technical and political aspects of fracking, along with a timeline that went back to about the beginning of this century, when fracking first began to arrive in Pennsylvania. It was useful for me to create it, though I don’t know how much use the students made of it during class. The beginning of this century, though, is about when they were born.

Including me, there were five players. The four students were two young men and two young women; the men were not sure about their own creativity, the women were convinced of it. They picked a range of overlapping character types: Visionary Moral Center (a middle school science teacher), Scary Chick (a New Age crystal shop owner; the player, a woman, allowed as how she might want to blow something up), Scary Moral Center (a Native American park ranger), and Scary Visionary (a would-be cult leader ex-con who did time for arson), all living in different rural counties (mostly their actual homes). I was a Rebel Pal, a sketchy landlord managing a bunch of rental properties in a rural part of the state where I had once lived (different from the rural part of the state where I live now).

We played a single episode. We did establish a couple-three of fin du millénaire elements relevant to the timeline: 9/11 (of course), “energy independence,” Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth (2006), Deepwater Horizon (2010), “sustainability.” The scene-setting phase, a Day in the Life, asks everyone to say a little bit about the characters, and say a little bit is what we did. The teacher was teaching his class, the park ranger was leading a tour, the crystal shop owner was having a tough time with her family, and the ex-con had found a janitorial job at a medical laboratory.

The Scary Chick drew the high card and opened the Voice step, talking to people in her shop about how bad fracking was. She only had low-value cards to assign to the step and we drew a face card face-up to represent the adversity. So things were looking bad! We introduced the mayor of the town, who stood to make a killing because off of the economic boost provided by the energy companies and was spreading rumors that essentially called her Satanic.

The next player was the Scary Moral Center, who had just gotten out of jail and found a job. She opened the Inspiration scene by describing her ex-con encouraging someone to open a coffee shop. I wasn’t sure how that related to fracking as an environmental problem, but the students offered how it might be connected to land use: coffee shop versus well pad, maybe? Okay, let’s see if that works as we play it out (and it did, more or less, as the scene developed). The cards showed that it looked like a favorable development. I think this is when lawyers started to get involved (that is, show up in players’ accounts of what could be happening).

I was next in the order, and had my landlord open Experience by having tenants complaining about the plumbing, water contaminated by nearby drilling. The next player, the middle school danger, opened the Action step; he was a little uncertain about what to do and what that meant, but I had fun acting as his students asking him annoyingly earnest questions about why no one was fixing the pollution caused by fracking. In the end, I think he had the idea for a campaign to buy up land to stop it from being fracked. The fifth player, as the park ranger, wound up all the way back in the Inspiration step, showing up at the coffee shop, not sure what to do. “Okay, so why are people going to say that this is the moment that changed everything?” I asked him. Maybe he sees a flyer about the fracking on the bulletin board, okay, and so he gives a ton of money to hire a lawyer. “He’s got some sort of nest egg that he’s willing to spend? Okay,” I said.

We were still losing in the Voice step, so we played another round. The would-be cult leader (Scary Moral Center) burned Inspiration for Voice, which made that a little closer. In the end, as the cascade of outcomes from the earlier steps (Inspiration, Experience, and Action) fed into the final moment of Voice, it looked like our campaign to buy up land was a success! Thank goodness for money and lawyers!

I pointed out the irony of having characters who were poised to fight for the environment as eco-terrorists wind up doing battle in court instead, and asked them how plausible our narrative was. The consensus was not very, given the amount of money and influence available to energy companies. The thing that I took away is that the game is responsive to the collective sense at the table of the mechanisms of political efficacy; I see now how the roles are supposed to structure what characters do in a given step, and that creates the flow of events from Inspiration to Voice.

And we interpreted one rules ambiguity a little generously, perhaps too generously. The rules let you replace (“cover”) a card put down by another player to improve its score if you have the role that trumps theirs. So the Moral Center can “cover” the Scary One, meaning that they can replace a low card played by someone with that role. But everyone starts with two roles! The more limited form of that mechanic would say, well, as the Moral Center you can cover a card played via a move permitted by the Scary One role, but not if they used their other role to play it. So, for example, if the Scary Chick plays in the Voice step because that’s permitted by her Chick role, a strict interpretation of the rules would say that the Moral Center can’t cover the Scary Chick’s card. A more generous (and, upon reflection, probably wrong) interpretation would say that you could, and that’s what we did.