Introduction

At one point my wife said, in reference to having powerful roleplaying experiences, “seeing is believing…and only seeing is believing.” She meant that you can talk all the RPG theory you want, but that ultimately if you haven’t experienced it at the table, you couldn’t really get it. Ron has mentioned (or despaired?) about this from time to time, and after a lot of thinking Jann and I decided to produce a product that could do exactly this.

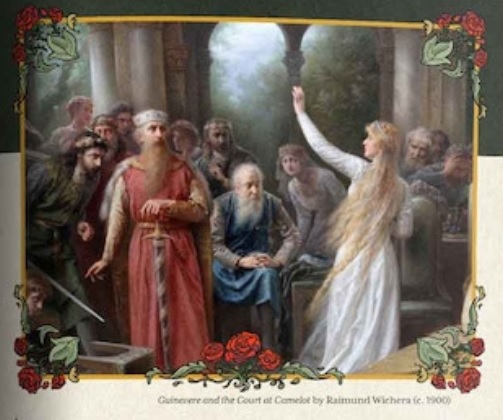

Enter Tales of the Round Table, an Arhturian roleplaying game with a twofold job: provide a concrete starting point for really showing new players an authentic picture of roleplaying without any extraneous bits; and offer an utterly transparent and clear example to veteran players of some of the core dynamics of what a roleplaying game is, especially with regards to emergent play, the distribution of authorities, and the nature of what Ron calls “story now” play.

What We Did

In order to provide this kind of experience in the most accessible way possible, we did three things:

We relentlessly made the game as easy to just pick up and play as possible (what the kids these days call “quickstart”). We did this in a few ways. First we used premade characters. It’s an Arhurian game, so all you do to start is choose a character card from among Arthur, Guinevere, Merlin, and the Faerie Queen. Second, there’s no rulebook (in the traditional sense). Instead, each player gets what we’re calling a “storybook”: a short booklet (Zine) with a series of guided prompts that teach you how to play the game while you’re playing it. There’s literally zero prep involved. You pick a character, grab a book, and start playing.

We got rid of a centralized GM role and distributed that authority among the players. On your turn, you play your character and choose one of the “problems in the land” that you want to confront for this scene. The player across from you plays whichever character you’re confronting and provides the opposition to your goal. The other players play the “muses” who set the scene and arbitrate the conflict. Once your scene is over, everyone rotates roles clockwise around the table and the next player opens a scene for his or her character.

We set the game in a familiar “fantasy” setting: the Arthurian legend. This is specifically a setting where there are a plethora of stories but in which there is no one, canonical version of the story. This means people have lots of images and ideas, but without any one path that they have to go down.

Fans of Ben Lehman’s Polaris will recognize some of our inspiration, but the game ended up being something else entirely. The players work through a series of scenes, and then play culminates in a climax scene in which everything is resolved for better or worse.

The basic version of the game plays a complete story arc in an hour, and the advanced one takes about twice that long. People call this a “one shot” in the industry, but I think that gives the wrong impression. What people have ended up calling it is a “short story” game. You’d have to play to feel the difference.

The Results: Less is More

You might be tempted to think that there isn’t much to the game. I think that’s true in one sense but not in another. We have worked hard – incredibly hard – over the course of about five years to trim down the actual mechanics and rules of this game as much as humanly possible. We wanted to get at the bare minimum for what a roleplaying game needed to function (characters don’t have any stats, for example). But at no point does the game suffer from being shallow. In fact, the game has fairly significant depth precisely because it doesn’t bother with fiddly details but focuses all its mechanics on facilitating the emergent, dynamic play that comes from the interactions of precisely-defined player authority and roles.

And because there’s no Game Master forcing the story into a particular end state, the dynamics are very different. It becomes quite transparent that the responsibility is on the whole table to respond to the story as it emerges and give it what it needs to go where it naturally starts to go. In a word, it makes an incredible demand on the players to listen well instead of merely being entertaining by speaking well.

Amazingly it’s the non-roleplayers and especially non-gamers who get this game right away. Something that taking this game to conventions and interacting with a lot of its players has taught me is that emergent storytelling is entirely intuitive to normal people. It’s us enfranchised gamers who seem to have the most trouble with it. There’s a lot to speculate about why exactly that might be the case, but what I’ve found empirically at the table is that the people who understand the game the fastest, who use the medium most skillfully, and who bring out its depth the most are those who don’t think of themselves as gamers. And for those of us who grew up enculturated into very specific modes of play, there’s a lot of unlearning to do, which is itself incredibly instructive. I know I’ve learned a lot.

Another thing the game does is tell you what sort of roleplaying you actually like. In the discussion about the difference between what Ron calls “story now” games (where gameplay is focused on exploring themes with moral content) and what he calls “step-on-up” games (where gameplay is about responding to challenge and/or competition), Tales immediately sifts out who prefers what. Playing with veteran games basically yields two reactions: “this is what I’ve always wanted in a roleplaying game” or “I see what you’re doing, and I see that it works, but it’s not really my thing”. In other words, it’s yet another tool for bringing clarity to discussions about roleplaying, but in an immediate, concrete way.

Conclusion

It’s been a real joy not just to work on Tales but to see the fruit it’s been bearing in the roleplaying communities around me. I’ve been able to introduce people to the hobby, like my father, who would never have touched Dungeons and Dragons with a 10-foot pole but who absolutely loved Tales. But playing the game with veteran gamers has also led to some of the most fruitful and interesting conversations about roleplaying design, play, and culture that I’ve had.

Tales of the Round Table is up on Kickstarter right now. It’s already well over-funded, so we don’t need any more help, but the Adept Play community is one of the main communities where I would love to continue playing and talking about this game. It’s been a real eye-opener for me and I’m guessing it would be for many of you as well.

One response to “Back to Basics: Designing Tales of the Round Table”

Robin Hood >> GoT

An interesting thought. Seems like a useful feature of many older source materials (as opposed to Star Wars etc., where it may be hard to escape canon). Robin Hood >> Game of Thrones, for these purposes.

(Not a hit against Martin, by the way — I'm just pleased with your observation.)