That was the pitch, but alas, I was far too ambitious, and ended up chickening out! Brief comments on the system, the play experience, and a few campaign design problems we encountered.

The Group: me (GM) with Fano, Tazio, and Luke. Fano and I are friends in real life; this was my first time playing with Tazio and Luke, and I hope to do so again!

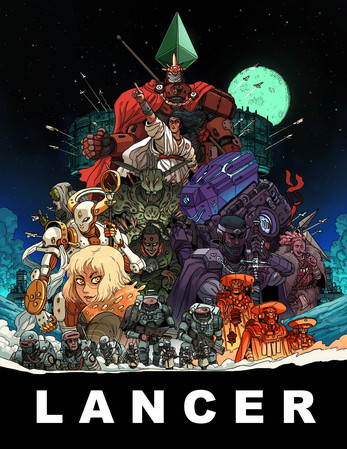

The Game: Lancer is an RPG about tactical mech combat in the far future–think Robotech, Dune, BattleTech, the Foundation, and probably a bunch of anime stuff I simply don't know. It is a ridiculously slick production, a monster of a 2019 Kickstarter that spawned a hyperactive Discord fanbase, with a four hundred page rulebook with excellent full-color art. It has a character-creation app, and an impressive degree of support on the Foundry virtual tabletop.

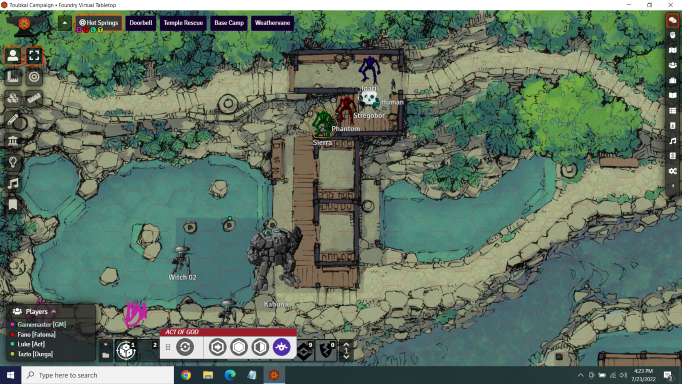

We played over Foundry, which has an almost vertical learning curve. The people who are into Foundry, really go all-out with fancy maps, lighting effects, "tokens," macro's, and so on. It's a whole hobby unto itself, and honestly I don't have the time. But! It does have pretty good support for this game.

Viewed solely as a "let me move my token around a battle map, roll some dice to attack, and then express my character with a quip," Lancer is an extremely solid design and quite approachable. That sounds like a backhanded compliment, but I don't mean it that way–it's extremely hard to design something like that, and it's a pretty smooth play experience.

Outside of mech combat, the system barely exists. Freeform traits, roll 1d20+X to get over 10 with some minor adjustments for difficulty. I ignored that part of the system almost entirely.

Below, you see the state of play at the end of our final session: the players chose to ignore their official orders to instead hunt down and destroy an enemy "ace," Stregobor (an invisible mech with a ferocious melee attack if you're spread too far apart). Combat was going poorly for them, until Fano charged into a melee combat and struck Stregobor down with a very lucky roll. Stregobor's allies look on in frustration from the bottom of the screen. (Map is available here. My own maps were terrible.)

As to the problems we encountered:

FIRST PROBLEM

The setting surely must be satirical. After repeatedly promising the reader an ambiguous utopia beyond our wildest imaginings, Lancer's ideal, well-meaning super-society turns out to be… Obama-era American liberalism.

Mulling this over, and the strategic accomplishments of American trillion-dollar war machines post 1964, led to the campaign premise, "Okay, but what if mechs are utterly absurd and it's your job to drive one?"

This doesn't marry well into a game that assumes super-stylish Good Violence. The idea of fighting a huge 2-hour artillery battle only to discover that someone at HQ screwed up, and you just massacred one of your own infantry divisions by mistake, is sort of a hose-job, and I found myself backing away from it conceptually.

Figuring out, "Look, you guys were sent by colonial powers to prop up a dictator against a rebellion that has popular support precisely because it repudiates your value system; you're doomed to murder people for no goddamn reason" into, "6-8 combat encounters punctuated with full rests" looked challenging from a player-relations standpoint, and also from a "Fuck, I actually have to use this set of ill-suited tools for that purpose" standpoint.

So, at least in this initial mission, I punted. Shakedown cruise, nothing too morally complicated. Let the players feel good, and then later missions could explore the contradictions in the society, the (likely) impossibility of the players' mission, and how they wanted to develop the situation.

SECOND PROBLEM

Running Lancer combat in Foundry VTT is not a spur-of-the-moment decision. You need a map with interesting tactical aspects. You need to decide on opposition forces with tightly-interlocking tactical capabilities. You need to slap all that stuff on a hex grid, and it won't take less than 2.5 hours to play.

In short, it's a lot of work that can't be done on 5 minutes' notice, at least, not by me. So "role-playing" mainly consisted of describing the current status of the mission to the players on Discord, asking them what their prioities were in the moment, and then slapping together a combat encounter.

There was no real exploration of character or setting, and thus it wasn't really role-playing at all.

I feel uncomfortable with that–if I were playing, rather than GM'ing, I don't think I would enjoy it much. But between the workload of getting the encounters ready, the campaign design trap I created for myself, and the game's (let's say) hands-off approach toward developing situations outside of combat, I decided that putting together four solid combat encounters was the best achievable outcome.

Sometimes you just want to move G.I. Joes around and go "pew pew!" It was fun on that level, and I'm glad the players got to complete a full mission cycle.

Ideally, this would now open up a lot more things to do and goals to pursue, maybe involving giant robots punching each other and maybe not, which would allow the players to make meaningful choices and shape what happens in this solar system over the course of several adventures. I'm not against running it again – I really like the little planet I made up, and the overall campaign concept still makes me laugh. But it would invovle a lot of time, work, and energy. Maybe next time.

7 responses to ““What if Catch-22, but with Giant Robots””

Giant Robots and Genre Expectations

It's interesting for me to read this and reflect on the game of Heavy Gear Rod GM'd for me and Sean last year. There are some similarities in the set-up: Heavy Gear also has a very detailed tactical combat game (it is meant to be able to be played as a standalone wargame) that doesn't connect directly via any mechanics to the out-of-mecha roleplaying. Rod was definitely able to look at the outcomes of the Gear battles and make use of those to determine how the overall situation changed, and how they led into the set-up of the "roleplaying" sections of the game (and vice versa). We took the setting material straight (although I think Rod pruned away a lot of it; necessary to do so with this kind of mid-90s setting-heavy game) and focused on the religious/political conflicts in the setting, but we also had a set-up where the missions given to the characters (potentially) conflicted with their personal values.

It's a weird place to play in: the tactical part of Heavy Gear is fun in its own right, and so as a player I wanted to "win" the scenarios. It was sometimes hard to figure out how to play my character (i.e., play her personal beliefs) in the context of the tactical game; or, rather, getting caught up in the tactical game made it easy to ignore or pass up on opportunities to express her character/beliefs. I can actually see this as a feature (potentially): i.e., mimicking the way focusing on a specific mission in a compartmentalized way can alienate us from our own values — though in practice it often left me feeling more straightforwardly that there was a disconnect between the two parts of the game. This was one factor that led to it taking me until halfway through the game (4 sessions in maybe) to get a handle on how to play my character (though once I did have a handle on her, there was less of a disconnect between the two parts of the game).

(An important difference between Heavy Gear and Lancer: the roleplaying sections are fairly detailed as well, with lots of skills with very specific functions.)

But it did get me thinking that its difficult to subvert a wargame by playing a wargame. That is: it's hard to make a story about soldiers who come to realize their mission is at odds with their beliefs (and at odds with what the professed values of their society are) when the medium for that story is a fun tactical game about giant robots shooting each other. There are some wargame designers working in that space (wargames that criticize or subvert wargames), like Cole Wehrle with his games Pax Pamir and Root, but it's pretty tricky and I think there's a limit on how subversive a wargame can be if it merely overlays satirical content on an otherwise straightforwardly tactical combat game.

(I'm reminded of music critic Greil Marcus's discussion about Ronald Reagan's cooption of "Born in the USA" as a campaign anthem: other music critics said Reagan was foolish for doing this because the lyrics of "Born in the USA" are not at all straightforwardly patriotic, but rather tell a bleak story that shows patriotism as a scam. However, Marcus argued — correctly, I think — that Reagan's use of the song was really smart because Reagan (or whoever made those decsions in his team) understoof that people don't actually listen to the lyrics: they hear the chorus "Born in the USA" played over an anthemic, rocking melody and they respond to THAT, not to the subversive material in the rest of the song. If you only know the song from its album version, it's worth tracking down the acousitc demo version Springsteen made for the Nebraska album, which cannot be mistaken for a rocking, patriotic anthem.)

I have one last thing to add: I do wonder if your desire to subvert Giant Robot tropes from the get-go may have boxed you in? That is, rather than starting out with the idea "I want to do Catch-22 with Giant Robots", if you had approached things with the idea that maybe "Catch-22 with Giant Robots" is what we'll end up with, but maybe we'll end up with something else, you would not have set things up for disappointment in that way? I.e., looking at subversion or satire as something that is potentially on the table for us to do as a group, but not necessarily something we start out as feeling we have to aim for. That's a genuine question, but I'm thinking of my current Champions Now game, where nothing in the starting two statements or set-up indicated that we would necessarily see our nominal heroes acting like villains, but rather left the door open for that to be one of the potential possibilities that could be (and was) developed through play.

Jon, I may need a few replies

Jon, I may need a few replies to respond to this.

"looking at subversion or satire as something that is potentially on the table for us to do as a group, but not necessarily something we start out as feeling we have to aim for"

As an American, I can't see a way of talking about modern military conflict without referencing Afghanistan, Iraq, and ultimately Vietnam. If I'm boxed in here, I'm boxed in by my strongly held beliefs about those wars. Neutering those beliefs would remove all desire to play the game.

But, there's a related question: why begin the game at the point with the PC's arrival in-country? Why not assume a lot of crazy shit has already happened, and the PC's have very complicated feelings about what they're doing but have renounced the official mission and are now trying to figure out what to do with that feeling of alienation?

The answer I have for that, isn't very satisfying to me now. I definitely agree I need to loosen up a few of my self-imposed creative constraints, I just gotta figure out which ones.

James

James

I think that's fair, but for some other perspective, I also think about the smaller conflicts. Grenada. Panama. Somalia. Balkans. These are also part of our modern American (and international) relationship with military conflict, though many folks don't think about them as much.

Speaking of Jon, Rod, and mine Heavy Gear experience, I would dare say it had overtones not just of the Cold War, but a few hot ones and even a dose of events undertaken on American soil by Federal and or State agencies. All of which have been controversial and tragic.

Quoting Jon here:

I have one last thing to add: I do wonder if your desire to subvert Giant Robot tropes from the get-go may have boxed you in?

In my own mind, the giant robot tropes are already a subversion. I have never seen them as Pro-War or even glorifying battle. I am sure there are parts of the media that do, but even my jingoistic youth-self recognized that there were anti-war sentiments in the giant robot stuff I watched or read about. Big heroes in a giant war machine carry a lot of power, in some cases the ultimate expression of armored warfare. But they also tend to be loners and to question authority; ingredients for subversive narratives to be constructed from. I think a great example of this is Robot Jox, which essentially covers this ground and ends with a big FU to the PTB.

My point being, that the idioms of subversion already exist within the material. I do not think you have to go too far to find them.

My own HG character was more cynical than Jon's, though the characters got on well. And she did not care for the way her society was going OR some of the military BS that was going on. But in the fight, Chalk was a professional all the way. I never felt that tactical and non-tactical play were at odds or if I did, I certainly do not now.

James –

James –

It may not be helpful to pursue this thread further, and if that is the case, I’ll certainly end it here, but I don’t think anything I wrote suggested (and I certainly didn’t mean to imply) that you should have neutered your beliefs or not engaged seriously with those topics. I do think that saying “Catch-22” and aiming for satire is a very specific way of taking those subjects seriously. And to also set yourself the task of subverting giant robot fighting stories while you’re playing a giant robot fighting game — that all seems to be a lot to try to make happen at once. Especially when you are placing all of that on your shoulders as the GM.

The Heavy Gear game mentioned above, for example, was critical of military interventionism (we took the topic seriously), but it wasn’t satirical and it didn’t subvert giant robot fighting stories. The potential for a more satirical approach — even a blackly comic approach — was there, but that’s not how it developed when we played out the situation.

Jon, my use of the word

Jon, my use of the word "neuter" was a sloppy choice of words in a post composed during a lunch break–I knew what you were saying, but I paraphrased it very badly.

Sean, I take your point that not all wars are black comedy, but I feel it's a safe assumption for many of them.

Likewise, I agree that there's a strain of anti-militarism in some of the operative assumptions in the game. But I feel there are deeper critiques to be made, particularly about Giant Punchy Robots themselves and a society that produces them (or their real-world equivalents).

In hindsight, this campaign was underway during the first few weeks of Russia's invading Ukraine. This is a (seemingly rare?) occasion where wildly expensive death machines actually do have a purpose, and using them is morally straightforward. It's almost certainly a much better fit for Lancer, and I probably should have just run with a similar concept, notwithstanding that it's been done a million times before.

A few thoughts from a player’s perspective

Sorry in advance for the disordered stream of consciousness. Also, thanks again to James and the others for what was a very enjoyable bit of tactical shooty robot drama.

Genre, Militarism, etc.

James' take on the setting as 'Obama-era liberalism' is a bit more savage than my own, which, based on a cursory reading of the book, is more like 'Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Social Democracy', with a more radical revolution having been arrested by various obstacles, and the titular Lancers potentially serving as the vanguard who will complete the revolutionary project.

I'm not making any judgement on which take is correct; it might even be a bit of a Rorschach test for the fictions were were each interested in exploring. I do think Lancer has the potential for a less morally compromised, but still amibgious, giant robot war narrative in the vein of the something like Iain Banks' Culture novels.

As a player, I definitely picked up on where James was going thematically, but I think there were a couple obstacles to engaging with it. The first was the simple fact of engaging with a new system, with a new group, and trying to find my feet. The second (which I think James alluded to over Discord) was the fact that this system needs a lot of time to breathe; I think it would take a few missions before our battles took on much narrative significance, because that significance is all established in 'narrative mode' and 'downtime', where we (hopefully) do the positioning or decision-making that shapes the game.

This last bit is speculation to some extent; the game really needs a a lot of time invested before you can cycle through multiple missions.

Prep and VTT Issues

One thing I've noticed as a GM playing other systems on VTT is that there is a strong temptation to try and gold-plate all of your prep with fancy maps, tokens, etc. Playing Lancer, though, I really didn't care how pretty the map was. Attractive maps are nice, obiously, but I had plenty of fun on the early, hand-drawn ones. If I were to try and run a game like Lancer long-term, I would probably try and improvise the tactical sitiuations, to the extent possible. I wonder what kinds of strategies GMs of games like 4e D&D have come up with for that sort of thing.

The Tactical Meat and Potatoes

This part really did work well. Not only did I have a lot of interesting choices to make, but I frequently felt that our characters were in actual danger, especially in the final mission. James did a good job of laying on the challenges; I'd be intersted to know how much he felt he was supported by the system in this.

As for quips and flourishes, I wouldn't say these were merely colour. Particularly in the final mission, were my character (Sierra) had landed in the middle of the action (literally) in his usual bull-in-a-china-shop fashion, and then decided to try and hold off some pretty scary enemy reinforcements so that the others could kill the target. Not only was this expressive of my character (jetpacks and radiators fuming, guns streaming shells, all the time), but the decision to stick his neck out and for two people he'd previously felt pretty cool toward carried real narrative heft, at least for me. The fact that his mech was then immediately hacked and turned against his allies was a delightful twist.

It ain't Tolstoy, but it's something. Whether I expressed any of this adequately to other people at the table is another matter.

I hope we are great minds because we definitely think alike

I ran two Lancer campaings (including their first published one, No Room For A Wallflower, which is an out and proud railroad), and I agree with a lot of your impressions.

I was equally frustrated by the setting, but I did like it… just not for this game. One thing to note is that Lancer boasts two authors, and I believe they pretty much split rules development and setting development duties in a way that does not help the game. The setting for all its extensive discussion of future space politics fails to address the main question of "how do I run a Mecha based story with this"?

I don't think it is a parody, just an attempt at a sort of realpolitik conflict of "how can we build a utopia when all these factions within our own government want it to fail". Which is a setup for intrigue, not for giant robot combat. The only way I think you can do the latter while respecting the spirit of the setting, is to drop your players in an already ongoing military conflict somewhere in the perifery, and make it clear that violence will happen regardless of their actions.

Also of note, the co-author who I believe focused mainly on the rules has a new game in beta called Icon, which is a solo project, and one clear difference frp, Lancer is that the setting, at least in its broad strokes, is designed to make the situations the rules cover a natural fit, and not something on the edges of the world.

Regarding this part, while I totally agree that it is not not a problem, I suspect the technical hurdles are less insurmountable than the narrative ones.

Yes, coming up with tactical maps and even virtual tokens is a chore, but after a while I did developed some speed and accrued a little library of resources. As the community grows, there's also more material freely available including maps for their first published campaign because (this will never not make me angry) the product doesn't come with any tactical maps, not even diagrams.

So, with practice, community and tooling, I think the challenge of making an interesting combat challenge can diminish…

…but what will always be there, though, is the in story need for characters to go and get on their G.D. robots for the core of the game to happen, which isn't easy to cut to naturally. During my first campaign (which I also mistakenly set in space) resulted in whole sessions without combat as I resisted (perhaps I shouldn't have) just jumping forward to combat encounters.

I did. A lot!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvXTC7LeIMI