Back in 2011 I submitted a game to the Ronnies based off the keywords: murder and whisper. I’ve played and revised the game quite a bit since then. I mention this in the spirit of full disclosure that the game I’m about to discuss is a game of my own making. However, I want to make it clear that this is not a design discussion. What I’m going to talk about isn’t a problem and it doesn’t need to be fixed. It’s just an interesting phenomenon that I’ve now seen multiple times when I’ve played the game. So, for purposes of this discussion, pretend I’m not the designer and this is just a game I played frequently and recently.

Haunted is a game about a murderer being stalked by the ghost of their victim. The murderer and the ghost are both dedicated to specific players and all the other players pull from a shared pool of supporting cast characters as needed on a scene by scene basis. There is no GM.

All of the characters have guideposts for play. For the murderer that’s a goal they are still hoping to achieve. For the ghost there’s unfinished business they regret not accomplishing in life. Supporting cast characters have either a need or a problem. Needs are something the character wants badly from the murderer. A problem is an issue the character is struggling with caused by the sudden death of the ghost.

This is the key driver of play: The agenda of the supporting cast players is to lay the needs and problems of their characters at the feet of the murderer to the detriment of their goal. Orthogonal to that, is the ghost who can only be seen and heard by the murderer. While the ghost has the ability to influence the outcomes of die rolls, they otherwise can’t directly interact with anything.

I had an opportunity to run Haunted at an online convention a couple of weeks ago and I saw a phenomenon played out that is actually quite common for this game and that I find completely fascinating. I’ll explain in detail but the short version of it is this: the ghost and murderer have nearly reversed experiences of the amount of agency the roles afford them.

In this recent game the murderer was Annie, an HR underling at a health insurance company. Annie’s goal was that she was seeking promotion within the company. The ghost was Annie’s live-in sister Sienna, who took advantage of Annie to leak information about unjustly denied claims. Annie then withheld necessary medication that led to Sienna’s death. As the ghost, Sienna’s unfinished business was that she needed to finish exposing the company’s life destroying practices.

The major supporting cast characters were Annie’s boss who had a need of turning Annie into a scapegoat for the leak. Annie’s boyfriend who had a need of wanting to take their relationship to the next level of commitment. Annie and Sienna’s mom who had the problem that she relied on Sienna for all the bureaucratic administration of her life. And, finally, Maya who was the primary patient Sienna was championing whose problem is that she now has no one to fight for her.

So here’s the first part of the phenomenon. After I get done explaining that the game centers all the action on the murderer, and that the ghost has no direct agency except as a voice in the murderer’s head, it is usually the ghost role that gets volunteered for first. The player often seems to be gleefully relishing the idea of a character role where all that will be asked of them is that they talk. It’s almost as if they are finally grasping at the chance for “pure” role-playing.

Then, somewhat more reluctantly, someone volunteers to play the murderer. Here’s the thing, it is usually the person socially closest to the player who volunteered to play the ghost, a best friend or a significant other in real life. It seems that knowing the ghost player creates a zone of social safety for playing the murderer.

This played out exactly in this recent game. One woman expressed early interest in playing the ghost, stating clearly that she found the idea of limited agency interesting. Then the other woman piped up and said, “Well, since she and I are friends in real life, I should probably play the murderer.” Thus, Annie and Sienna were born.

The phenomenon then extends into play like this: by default, the ghost can only be seen and heard by the murderer and they can not influence the physical world in anyway. They can influence the outcomes of conflicts initiated by others but this is very much a “helping” mechanic toward other characters’ goals. This help is accompanied by visibly supernatural effects. But otherwise, they have no ability to enact an agenda of their own except perhaps what they can literally talk the murderer player into doing.

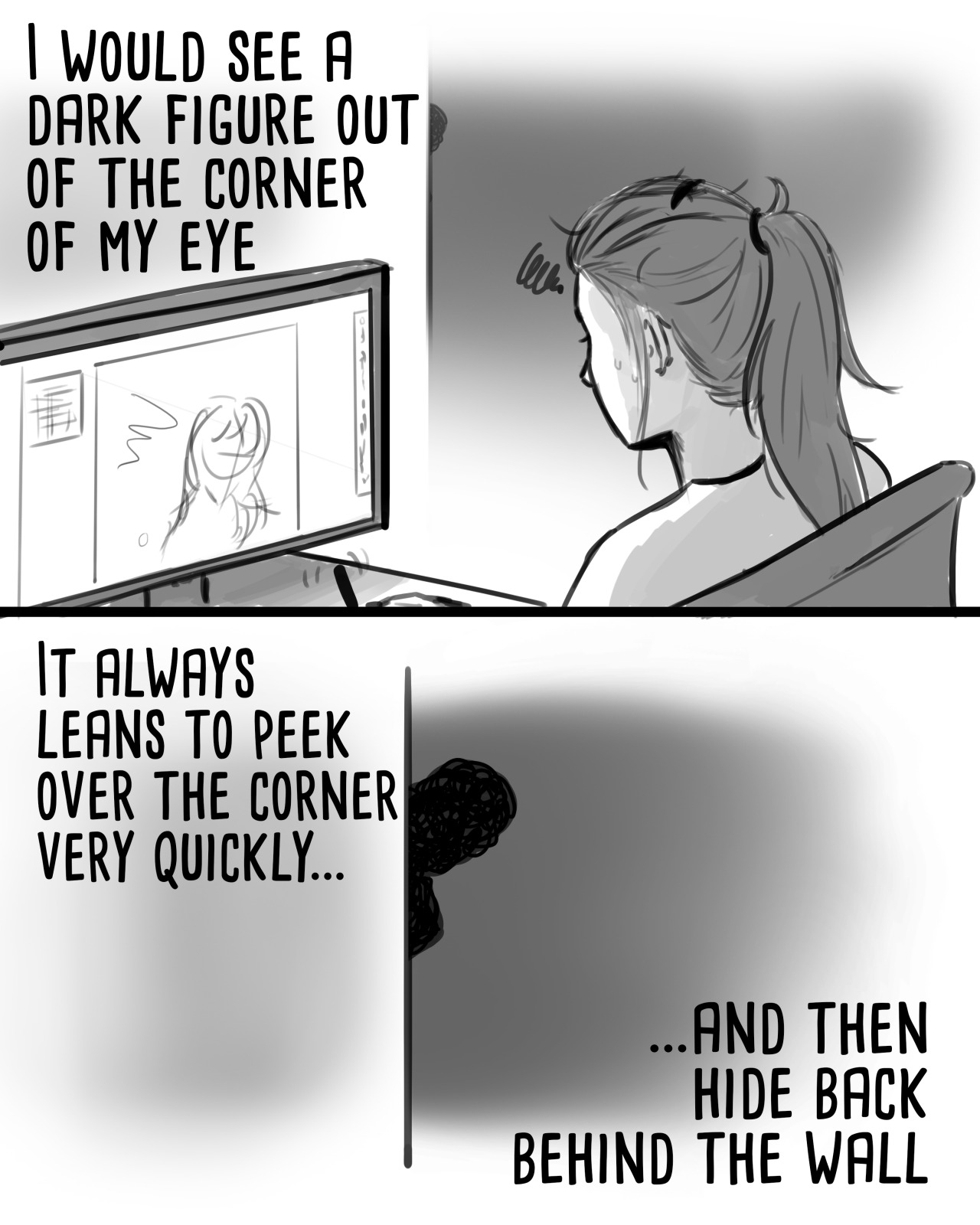

In my mind, this is a horrific “trapped behind glass” situation. But in play, the ghost player is usually one of the most enthusiastic players, perfectly happy to be a running commentary track on the main action and to place their hands on the scales of conflicts from time to time. They behave as an incredibly empowered player and seem to have no issue with the fact that they technically can’t make anything happen on their own.

In this recent game Annie’s player decided that despite having engineered circumstances that appeared to be natural causes, she actually had a panic attack and ended up dumping Sienna’s body in the ocean. This led to Sienna’s player taking a more hallucinatory approach to her haunting such as having the room appear to slowly fill up with water as Annie’s boss leaned into her about the source of the leak. It was a very cold, wet, and at times almost cthuloid-esq game. This was all at the direction of Sienna’s player as she had full authority over what haunting looks like.

Conversely, the murderer, who is the focus of every scene and is fully empowered to call for a roll at any time with whatever stated goals they desire (limited, of course, by the circumstances of the scene), frequently ends up retreating faster and faster as the game goes on. It is not uncommon for that player to say things like, “I feel trapped” or “there’s nothing I can do” or “I don’t see a way out of this.”

I am reminded greatly of the behavior Ron described from The Frog Pool game:

Closing off options or narrations with “I can’t,” including but not limited to claiming Traits don’t apply when they often obviously do or could. “This is a situation I can’t escape from, and I understand that you mean it that way …” “I can’t kill the snake …” “I could do it if I weren’t looking for Urrop …”

In this recent game, this largely applied to Annie’s work life. As her boss zeroed in on her as the source of the leak, the more the player seemed to assume Annie’s job was all but lost. It manifested in her personal life as well as both her boyfriend and her mom seemed to increasingly take over her life. Now, some of this is admittedly due to the fact that mechanically the odds are not in the murderer’s favor, especially at the begining of the game. However, there’s a far cry between “long odds” and “hopelessly not worth attempting.” At one point Annie’s player came up with the interesting idea of swapping her compromised work computer with her bosses, but looked at the dice and just said, “No, nevermind.”

Now this hasn’t been the case in every game. I have seen murderer players who dive in with gusto and push forward despite the odds. But they are surprisingly rare. This recent game matched the more frequent pattern I’ve seen across multiple games.

I’ve just been completely fascinated by the observation that the ghost is designed to have little to no agency, while the murderer is desiged to have all the choices and drive, but the emotional experience from the players’ persectives are often reversed. It’s such an interesting phenomenon I figured it was worth posting about.

4 responses to “A Tale of Two Agencies”

Player Feedback

I am curious if the players offered or you solicited any feedback directly from them on the phenomena? Did any other players have any thoughts during the game or after?

Not exactly. It’s something

Not exactly. It's something I've observed over many games. Players talk after the games, but it's mostly repeating what I already posted. The murderer often says they felt trapped. The ghost remarks on how much they liked being a voice in the murderer's head.

The murderer is obstensibly supposed to be pursuing their goal. There is also a mechanism by which the murderer can gain mechanical strength/improvement and it involes resolving supporting cast members needs and problems (but it isn't the same as just surrending and letting them drown your life). This did lead one murderer player to comment, "It's odd. I feel like this is an RPG with a win condition, but I couldn't see a path to it."

I hadn't played the game in a while and it was all The Pool talk around here that put it in my head. The core resolution system is a modification of The Pool (base dice plus expendable resource) plus Sorcerer (opposed rolls, compare high die). When Ron posted about The Frog Pool game I recognized that I had seen a lot of those issues when playing Haunted, especially the one I quoted above. It made me want to play the game with an eye on smoothing those things out.

And it mostly worked. Scenes were clearer, dice rolls had more immediate and obvious results. Play was overall smoother. But the one that didn't change was the murderer saying, "I can't…" or "It's useless too…" or whatever despite having the dice right there. They weren't even particularly low on the expendable resource to improve their odds.

I'm curious about this phenomenon of players imprisoning themselves in their own sense of the fiction. It happens A LOT (but not always) in Haunted with the murderer. It clearly happened in The Frog Pool game. I know one person for whom it almost always happens regardless of what game they are playing much to the frustration of another friend who runs games for them frequently.

Haunted just seems to be an interesting test bed for this because (a) it happens so frequently with the murderer and (b) has a built in counter example of a player who IS imprisoned by the fiction but almost never experiences it that way.

As is typical for me, I have a habit of observing a repeated player behavior whether within one game, across similar types of games, or just in general, and drawing a big red circle around it. Why does this happen?

Way too much to be talking about on a holiday evening

I will get to the terminology later or maybe a lot later. Right now I’ll talk about this without using what is evidently a loaded term. My thesis: let’s not confuse a character’s range and scale of effect for the quality that you’re comparing between the two primary players in Haunted. Unfortunately, to talk about that quality, we have to get through some layers.

Part one (which is merely introductory). Here’s the foundation or context to get past. Let’s not confound differing scales of Situation authority with dishonest control exerted across persons. The difference is easy to demonstrate:

[for purposes of the conversation I am setting Backstory authority aside, to avoid rabbit holes and because it’s pretty easy to see the equivalent issue anyway]

Historically, the first, rather ordinary, functional distinction became the standard excuse for the second, toxic control, which is antithetical to play. This construct stinks up the room, preventing the discussion of real differences among persons during play. Everyone’s already in a defensive crouch. In this case regarding Haunted, I’m not pointing out or referring to the control issue as a problem during play, but I’m saying that the relevant topic is already fraught when it shouldn’t be. Let’s acknowledge that and move on.

Part two (in which I almost get to the point). The real variable which I think you’re talking about isn’t a rule or a mechanic or identifiable design feature, but an effect of good design and authentic play. It is the outcome for play which relies on this person playing, given all the same variables of fiction and game mechanics, as opposed to any other person who could have been playing instead.

Let me use a very straightforward example. Perhaps surprisingly, many combat systems open the door for it to appear. You have a character with a given percentage of striking successfully, a given array of defensive or protective features, and a known quantity of resource (life) at present. The complicated fight ensues with many characters involved … and your guy takes a heavy hit from a foe, almost right away. It was more damaging than an average hit at this point of play.

You’re engaged fully with the fiction of play, and you like the characters and care about the situation. Emotions and numbers are indistinguishable, which is a good thing: (i) you lost more of that resource than you were expecting, and (ii) it hurts. The question is, what do you do on your next move? Jesse A, in Dimension A, says, “Ouch, I’m moving back and getting that healing potion out of my pouch,” letting an ally step into the breach – but over there in Dimension B, Jesse B says, “Ow! You fucker!,” and states whatever charge or leap or other combat maneuver or mechanic indicates a full-on, possibly lower-defense attack.

I am not discussing tactics as such, although they should be acknowledged as a piece of what I’m talking about. I’m describing the the difference between Jesse A and Jesse B at this moment, especially when this difference is permitted, known, desired, and embraced by everyone at the table. People know that the alternate dimensions exist, or rather, they know that they don’t know which one they’re in. The rules don’t make that difference. There isn’t a “right thing” even if there’s an optimal tactic thing. The precise use at this time is personal: it is contextualized and given shape and even potential weight by the instrument, but it belongs to this particular Jesse.

That was merely an intentionally accessible example. What I’m talking about may apply at any scale of effect and at any distribution of authorities. It may also apply given any minimally-functional distribution of spotlight.

We live, unfortunately, in a bad history for this quality. A lot of RPGs feature busy mechanics or formalized loud talking, including increased ranges and scales of effect, which do not afford this feature because different outcomes don’t make much if any difference. A lot of play therefore features fake choices and extravagant posturing which demonstrate its absence. So let’s acknowledge at this point that people are often puzzled about something they’d like but don’t know what it is, and trapped by something they do which doesn’t achieve it.

Part three (the point, finally). The difference between the ghost player and the murderer player has nothing to do with the precise differences in authorities or scope of activity. It is not solved, for example, by equilibrating some metric of effectiveness or an alleged freedom for talking. The difference lies in their different perceptions of their personal presence in play. The ghost player says, “Hey, me, myself, and I get to respond and act and, basically, to play!” and the murderer player says, “I have one job, to avoid consequences, and whatever I say or do just does that one thing or fails at it.”

If the murderer player sees their individual, personal presence in play as inconsequential, i.e., there is no Them A or Them B, and in fact you could put a compliant baboon into this chair for the same basic outcomes during play, and if loud colorful talking doesn’t seem to be making any difference either, then they’ll hunt about looking for something to blame.

Dice or equivalents are an obvious scapegoat, because no matter how high the odds, they can in fact fail, and one of the false presumptions that gets stuck in one’s head is that if only they keep succeeding then that will solve the issue (it won’t). Same goes for anything else they might gesture at. They might say, “The ghost can do more than I can,” even if that’s not true in raw fictional terms. They might – and as you say, they do – say, “I can only do this tiny little action which has such a tiny little bit of effect,” even if that’s not true either. They might say that another player, especially if there’s a GM, is stopping or preventing them in some way, even when that is absolutely not the case. It totally doesn’t matter what they say, because they’re trying to find something, anything, which corresponds to that lack of personal identity which they are experiencing.

I know you don’t want this to be a design discussion, so here’s my best shot at a framework for thinking about the phenomenon.

With any luck this context and framework may work or help with your thoughts on your observations.

I will finish by saying that I use the term “agency” for exactly this personal-presence quality in play, and that I consider it – like Bounce – to be an effect and property of many different design variables, not any single mechanic or feature. I think what you’re calling agency is irrelevant to the issue.

I knew going in that I was

I knew going in that I was using "agency" slightly differently from the way you use "agency" but I also couldn't think of a different word, so I went with it. I'm glad to see it didn't confuse the issue.

At the end I can see there is a clear question: Is Haunted (a) a fine game that just so happens to really highlight this aspect of damaged gamer psyche or (b) does it have properties that evoke this issue in full, regardless. I’ll take that as something for me to ponder.

However, this…

…made me realize what the difference is between the games where I have seen this behavior and the ones where I have not. It occurs when the murderer player loses sight of their goal and, as you say, sees themselves as only dodging consequences. When the murderer player stays clear headed about their goal and sees the needs and problems as adversity toward achieving it rather than just monkey shit being thrown at them to dodge, the phenomenon doesn’t happen.

There are two stand out examples. There was a game where the murderer was a corrupt cop who killed their partner. Their goal was basically to steal a bunch of drug money and get out of dodge. The resulting game was something like Breaking Bad or a Tarantino film. A violent ghost haunted neo-noir.

The other game was one where a creatively frustrated film director killed his producer. His goal was to finish his movie, his way. The result was actually pretty funny. It reminded me of a Coen Brothers-esq comedy of errors about trying to make an authentic film in the face of corporate studio bullshit and the soap opera of inappropriate work relationships.

(One little design note because it’s relevant to the topic: I added needs and problems when I saw a similar issue with supporting cast players. I saw a lot of shrinking away from the murderer rather than bringing adversity. As the facilitator in a GMless game I found myself doing a lot of “directing” I didn’t want to be doing. Functionally, I was teaching people how to do a common GM task. I added needs and problems as a way to “jump start” that process and have always been a little concerned it’s over compensating. But again, that’s for me to noodle).