Over six months, I scoured the internet for West Marches resources. Ultimately, I produced something that could be played with a rotating cast of players in a persistent world using D&D 5e rules. 5e was chosen for its popularity and perceived accessibility. I used strict GM-as-neutral-arbiter style play with little to no punch-pulling.

After nine sessions (four hours each) across twenty-something players, I can call the project a conditional failure. Very little emergent play manifested. As an experiment, it was a success since I’ve learned much in a controlled setting.

Context

Introduction

Popular Culture is interested in RPGs but doesn’t understand them. It knows it involves dice, paper, perhaps miniatures, and an ingenious director who infuses these artifacts with meaning and imagination. Sometimes play is depicted as a kind of extended play-acting but occasionally it’s depicted as an elaborate simulation, an imaginary world substantiated through shared commitment. This might explain the authority of the rules-master, the binders, and the militant obsession of its participants.

Ben Robbins’s West Marches suggested this dream could be realized, could include players both new and veteran, and could be popular. All at once.

Over six months, I scoured the internet for West Marches resources. Ultimately, I produced something that could be played with a rotating cast of players in a persistent world using D&D 5e rules. 5e was chosen for its popularity and perceived accessibility. I used strict GM-as-neutral-arbiter style play with little to no punch-pulling.

I’ll say something about my interest which is simple. I want more players to access emergent play. As the unique feature of games, emergence is very important to me. Here’s a short overview of my definition.

After nine sessions (four hours each) across twenty-something players, I can call the project a conditional failure. Very little emergent play manifested. As an experiment, it was a success since I’ve learned much in a controlled setting.

Goals and Techniques

- A hexcrawl. See here.

- Nearly consistent with 5e’s systems for inventory, overland travel, etc.

- Accessible to (completely) new players.

- Referee-style GM. No introducing/removing major game elements during play.

- Players coordinate/speculate about the game/make plans outside of the sessions.

- Players explore the freedom offered by this style of play.

- Stick to the 5e Core Rules.

What I Created

I spent at least thirty hours searching for resources, watching actual play, reading source material, and compiling it. The setting was a ruined empire on generic Scandinavian islands. I welcomed this genericness for its compatibility with DnD materials and as a blank canvass for the players.

- ~110 keyed hexes

- 16 dungeons (taken from thousands of one-page-dungeons)

- 8 random encounters for 12 regions

No one I talked to trusted 5e’s rules to handle something like this and I followed suggested modifications from people with actual play experience. Source.

- Players manage their own map with Miro.

- Clever “Very Random Encounters” engine where each encounter happens at an independently random time.

- Only meaningful rolls. Players always know the DC and the possible outcomes.

- Simplified inventory emphasizing food and water.

- Seafaring.

- Simplified travel rules (all modifiers to speed are ½ instead of 2/3rds, 17/19ths, etc.)

- XP rewards for proactive play.

- Blackball’s treasure.

Actual Play

Overview

Each game was played online using players from my 200+ person Meetup group. Since it was online, Meetup recruited people from across the US. I had little participation from recurring members of the Meetup group’s local members.

Play involved getting new players up to speed for an hour and then three hours of play. What was play? Mostly the players trying to agree on what to do. Aside from rules stuff, I spoke little.

Play was functional, consisting of D&D staples. Managing inventory, making roll after roll, asking questions, coordinating the party, talking to NPCs. Player’s flirted with the idea of taking bold risks or pushing the game’s systems to their limits but aside from some early experiments they stuck to typical procedural play.

The format of, “You have four hours to do whatever” was strictly adhered to. This openness was challenging for some, strenuous for most, and crippling for a few. But why wouldn’t it be? They shouldered many of the responsibilities traditionally hefted onto the game master. They managed pacing, balanced participation, and interest. If someone did anything irresponsible/fun, it risked hurting the other players’ play experience.

Was it fun for the players? I suspect about half the time. Most sessions had a “major conflict”, usually a desperate combat encounter they barely crawled their way out of. The only recurring feedback I ever got was, “Have you considered not sticking to the rules?”

What Worked

- The Player Map. Players that got it tended to enjoy the game. Mapping out a journey to accomplish goals, when it was attempted, was challenging and satisfying. The hexcrawl systems (simplified travel, weather, inventory) enforced this and worked well.

- Independent Random Encounters led to many novel and interesting situations. Encounters could happen simultaneously, at any time of day, in numerous locations.

- There-and-back-again formula. The players had four hours (really 3) to go on an adventure and make it back in time. This was both salient and challenging.

What Didn’t Work

- Players struggled with every aspect of technology. Using a microphone, Discord, Google sheets, the dice roller, signing up on Meetup, all of it.

- Players didn’t use Discord to coordinate. The West Marches dream is predicated on players forming their own groups with plans. This never materialized.

- Players created characters using a program and, consequently, didn’t know their character’s abilities. The program hid the clunky mechanics of the game between a veneer of dress-up, hiding tactical decisions between dozens of cosmetic choices.

- Teaching New players. System-focused play is fundamentally incompatible with not knowing the rules. Using other RPGs, I’ve had wonderful one-shots with new players but DnD’s rules are too complicated and unintuitive for this to work well.

- XP rewards for proactive goal-oriented play. Players often ignored obvious opportunities to meet their goals (instead, focusing on trivia) but were disappointed with their lack of XP at the end of the session. Some players wondered why I didn’t just give them XP for showing up like their total responsibility should be to “play and have fun”.

What I learned

Setting Expectations is Hard

I could not convey what the game was to new players. I thought “persistent world” would be a salient concept. It was not. The community did very little to help new players (except for one noble soul) and most did little to ask questions, learn rules, etc.

The idea of expressive systems is foreign to popular culture. All felt the burden of understanding the game’s mechanics. Few appreciated the reciprocal freedom.

D&D is Complex

Players struggled with many aspects of D&D rules.

- Derived stats.

- Using the Player’s Handbook as reference.

- Optional classes and races. The encapsulation of “Core Rules”.

- How/Why rolls are called.

- D&D cares about treasure and combat fitness. Many characters had low “primary attributes,” so we had warriors hitting with a d4+0.

Conclusion

The dream of letting a large group of diverse players explore a persistent world is just that. Like it or not, players cannot fully participate in an RPG (or any game) without an understanding of the rules/play procedure.

On the other hand, Hexcrawls and persistent worlds can be fun and rewarding even in an “inappropriate system” like 5e. Making random encounters independent of each other adds immensely to their variety.

Lastly, I’ll say something about my own enjoyment. Refereeing isn’t particularly challenging or creatively fulfilling so what did I expect? I was looking forward to seeing the players working together to bring an imagined world to life. Roleplaying is magic. But it’s a magic that is impossible without dogged critical imagination and deep empathy.

I gave my anonymous players freedom but no responsibility. In other words, what I created was a commodity. And magic cannot be commodified.

10 responses to “Death Marches: A Conditional Failure”

Out of playtime commitment

I have had almost no luck with getting players to engage with a game out of session time. I have done it myself, as a player, in Eero's Coup de Greyhawk, but that is almost the sole case I have witnessed thus far.

Planning? Plotting? Designing something? Throwing out ideas to the public? Drawing a map of the city you are rebuilding? Essentially no luck. This even with people I know socially and meet face-to-face, and who think about the game significantly. I would have absolutely no hopes of this with random internet folk, no matter how excellent players and good people they were.

Now that I think of it, I have seen character optimization happen outside play, voluntarily, done by motivated players.

Maybe asking for this as part of pitching the game might have some results. But I would not count on it.

Planning? Plotting? Designing

Right. It wasn't my intention to for random internet folk to form the player base. I was aiming it at the 200+ local Santa Cruz people with whom I've had great experiences with. But Meetup doesn't let you host online games without opening them up to the entire globe.

I'm also guilty of wishful thinking.

Some thoughts

I think I detect a sense of frustation and I am sorry that is the case, It sounds like you put a lot of work and effort into this. I did not put nearly as much work into the Chaos Marches and I had a mix of good and bad results. Mostly good, but it was different in a lot of ways. I do haev a few observations.

-I think there is a "serve me up some fun" mentality in gaming that has persisted for a long time. I think this directly relates to Ron's Saliying the "The". A GM is expected to organize and prepare and know / teach the rules, while a player is expected to PLAY. West Marches by definition has to have a mentality of players as partners and organizers, else it continues that existed before its implementation. How many people don't play until someone invites them to play? Lots.

-While I think that Forbidden Lands or Runequest or Tiny Dunegons makes for a better fantasy hex crawler, or older editions of D&D, I do not think D&D is the problem. A fixation on D&D IS a problem, but not the issue in this context. I've seen people fuck up the easiest of games because they are not invested.

I would use the word service, but commodity works just as well. As a culture we service as something performed by an inferior; if you were any good, you would not be on your knees serving. And I suspect many players do see a GM as a servant or providing a service. This is reinforced by many bad habits but also things like pay for play, where running a game is commoditized quite literally.

Sean and Tommi, agreed that I

Sean and Tommi, agreed that I am seeing many connections to "Slaying the The." I'd be interested in hearing about what you've identified as constituting a 'successful group'—one that doesn't leave one person feeling like they're merely providing a service to the others.

My guess would be that one essential ingredient is a distribution of some of the responsibilities Ron describes in that post. Most of the traditional GM responsibilities may belong to one person, but I think if the group isn't stepping up to cover some of the responsibilities—of hospitality, of proposing games, of relationship management—it won't hold together long.

Hi Noah,

Hi Noah,

Maybe my answer to Badspeler below gives some indication of how to make a game of this kind work? At least a few active players, or players that take it upon themselves to get the play started from the initial state of paralysis.

In particular, I do not think that, aside from West marches and I guess some other particular methods of play, player activity outside the sessions is strictly necessary. I do find it to be very helpful; different kinds of accounting and planning can be at least preliminarily done outside active playing time if players so will, and then playtime can be used on more pressing matters that involve more players, or for finishing the planning with a better knowledge base.

I have yet to listen to the mentioned video; so much backlog.

Player Agency and Organization

The game adhered to formal rigid systems, including hexcrawling, and I'll say something about how the players responded to it.

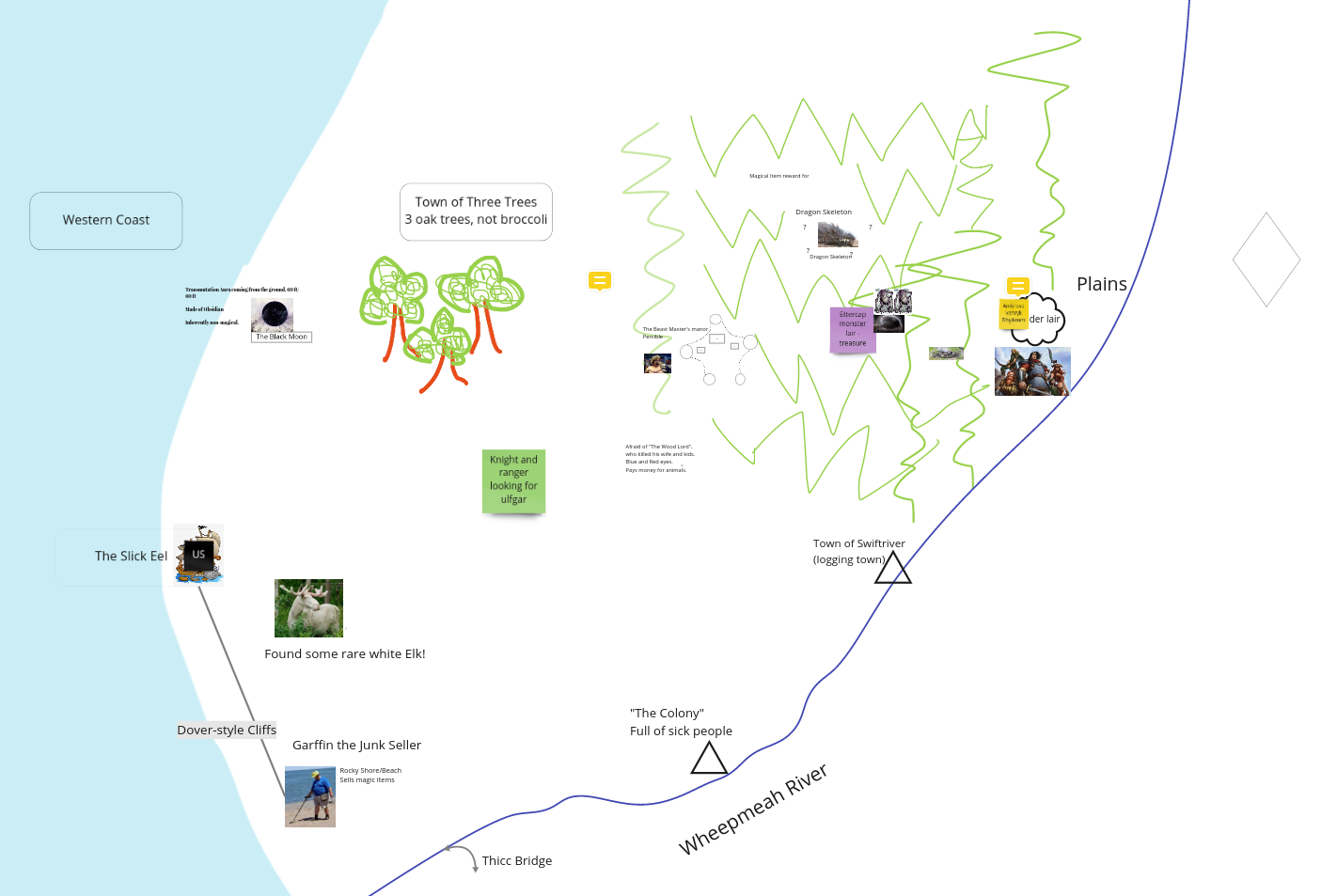

In hexcrawls, there is a large premade map overlayed with a tiling hex-grid. Locations and land features are determined so that traversal is challenging. In my case, I started out with this map-

seen in full here (https://arsphantasia.wordpress.com/2014/03/09/the-isles-of-mist-a-free-hexcrawl-adventure/).

I never showed the player the map. Instead, they created and managed their own using the software Miro using descriptions and cues I gave them. The rules for hexcrawling were taken from the same module as the map which were themselves adapted from the Alexandrian's Blogpost.

Here's the player map. Most of it was put together by a handful of players. They were usually grateful for what existed for the map but almost always hesitant to *add* anything to it for future players.

None of the players had ever played in a hexcrawl before, even the few veteran D&D players. A few were quite positive and supportive of the idea but most just followed it quite procedurally. That is, they considered the vast wilderness as a great space "between things".

The level of disruptive play was startlingly low. Players accepted the slow procedural play stunningly well. If I were playing, I think I'd go a little stir-crazy until I realized the GM was open to wacky system-pushing play. I didn't see any rules-lawyering (I had a couple of players slightly frustrated with small errors I made at a couple of points- using Investigate and Perception interchangeably. Again, play was remarkably coherent and functional.

Many of the players came into the game thinking it would be a venue for character celebration (or so-called princess play). They would spend a lot of time with the character-maker choosing their specific sub-race of dragonkin and five-page backgrounds. But none of it made it into play. It all fell before the oceanic might of rigid play-procedure.

The hexcrawl stuff *did* result in interesting situations. I'll list a few here.

Now, I doubt that any of this made them feel heroic or endowed with creative agency. The agency part should come from things like using available resources in clever ways. In that department, I tried my best to shower them with things like boats, gold, magic items, animals, friendly NPCs, inns, and quests. Instead of having shops stocked with magic items, I had a simple rule where they could search a town for any magic item in the DMG.

But they literally never did any of this. If they pushed at all, it was only in the usual boring ways of rolling favorably for their stats (no one who rolled for their stats ever rolled badly) or playing a strong class or race from outside the core materials.

When the players encountered a boat that mysteriously crashed ashore filled with treasure, they just took a small percentage of it and left the rest there. One of the players, after earning mithril armor just sold it and added the gold to their large inventory. After retrieving several mushrooms with divination power, they got tossed into the inventory never to be heard or seen again.

The effectiveness of the party was about equal to how well organized it was + how often they listened to my suggestions. After some encouragement from some OSR folk, I started being very proactive with my suggestions as well as positive feedback.

Party government never really emerged. People thought it was extremely important to respect each other's autonomy and rarely overran each other. Most decisions were made slowly after I asked each player what they did over multiple rounds. Near the end, I suggested they use a party leader to "lock-in" the party's actions but it wasn't that different.

This is *very* different from my experience in games without natural turn/procedure mechanisms. There, players often talk over each other declaring as much as possible.

I'll probably do a follow-up with some of the players over the next few weeks and I'll pay special attention to their perceptions of their own agency. My feeling at the moment is really this. The players felt that play procedure was really what the game was *about* instead of, "The minimal amount of scaffolding to make time, location, and resources matter," which is how I saw it.

I have been playing in Eero’s

I have been playing in Eero's Coup de Greyhawk and what happens there is that the most established players take the lead. But there is a core of persistent players there who have a clear agenda and the knowledge to make strategic decisions.

When I playing in a few convention games of Vetehisten virsi, which was essentially a series of one-shot sessions in a persistent world with persistent characters unless players wanted to make new ones or had to do that, some player knowledge was distributed by giving the notes of the previous players to the next batch. There was a fair amount of effort spent on figuring out where to go and each session felt like an investigation of the adventure location, whether it had or had not been investigated by previous players. It was set in a highly geographically limited area.

In the first session of Vetehisten virsi that I played I took the role of figuring out what had happened in earlier sessions and applying that to what we were doing. Thereafter my role in the group was getting us to do something fruitful (and then in paly I went to the role of figuring out what is happening and trying to solve problems; great fun). At this point I had little experience as a player in a sandbox or OSR game (this used Lamentations as the rules framework), but I did have refereeing experience in the method and knew what was going on.

West marches is fairly demanding of players in the sense that at least some of them should be active, and it may not provide too many clear paths, though hopefully some rumours or other leads did exist. Maybe it would benefit from having a player or three who know what it is about and can get the game rolling?

It would be interesting to play in your game at some point to see what it is like.

More Backstory?

Thanks for this interesting write-up. Was there any overall backstory to the world you created? I wonder if this would make a difference.

For example, suppose part of the world's backstory is that one or more major threats are on the rise, so part of the motivation for exploring or dungeon delving is to find more information about (or weapons to fight) these threats. Or, there's an organization like Circle Knights (from Circle of Hands) that gets sent on missions to areas where there's trouble.

Social Glue

Badspeler, it turns out I have a lot of experience with this. From 2008 to 2013 or so, my gaming crew ran about 300 sessions of one West Marches type campaign using 1981 D&D; a sub-set ran about 50 games using the 1974 version. So those were very successful.

But we also had a ton of failed experiments too. It was the same pool of people, using the same in-person and on-line venues, for the same (or very similar) game designs.

The only variable I can really identify is group social cohesion. The subset that went for 300 weekly sessions – those guys really enjoyed playing together, as people. On any given session you might have 3-7 people out of a core group of 12 or so (maybe up to 20 if you count people like me who would drop by once in a while). But most combinations of those core 12 people were a hoot socially, which made it easier to keep coming back, and made it more fun to invest in the game.

The Red Box gang got a huge lift because a bunch of us were friends before. So, early in 2008, if you showed up at a table with Adrian, Scott, and me, there was a very easygoing goofball vibe of people who were happy to be there. We were pretty good at making shy new people feel welcome, and we understood that was a huge priority. Eventually we built up enough people with a similar attitude that it became self-sustaining, at least for a few years.

But not every combination was as much fun. There were experiments where the main participants didn't gel, and without a core group of committed people it just couldn't keep going. This is on top of things like scheduling difficulties and so on.

Any prolonged social activity requires commitment from the participants. I show up to work because someone pays me, but I hang out with people in my free time because they're my friends or it's something that genuinely interests me (preferably both).

I don't think you should feel bad that a purely online group of randomly collected strangers burned out. It is absolutely amazing that it lasted so long, and that's a huge testament to your skill as an organizer and player.

Your own subset

I'm interested in the events, characters, and general outcomes for the sessions in which you played directly. What was it "like" insofar as that limited group of players, including DM, is concerned?