My son Erik, 11, joined me for a visit to Ulf’s in Göteborg (Gothenburg), for a one-night session of play. Ulf was kind enough to run things and to include his daughter Alice and son Franke, as well as another adult, Andreas, and Erik really wanted to try 5th edition D&D for his first time role-playing. We played in English, although I was the only one at the table who “needed” to, and I think I might have made it through in simple Swedish. Next time perhaps.

My son Erik, 11, joined me for a visit to Ulf’s in Göteborg (Gothenburg), for a one-night session of play. Ulf was kind enough to run things and to include his daughter Alice and son Franke, as well as another adult, Andreas, and Erik really wanted to try 5th edition D&D for his first time role-playing. We played in English, although I was the only one at the table who “needed” to, and I think I might have made it through in simple Swedish. Next time perhaps.

Any posting about D&D is fraught, especially regarding whatever is purported to be the current version, when it should be considered “a,” that is, singular game with its own design. This session is full of distinct topics for me which I can only list as clickbait, or at least, as desired separate topics in the comments.

- The game as such: “old school,” my pink ass. It’s Fudge.

- Inspiration Points tie directly to my consulting sessions with Tor (Proto-concept from D&D play; The merchant’s wife); I call your attention to Erik’s interest in experience and leveling up, as the rest of us ignore it in our attention to Inspiration and hit points.

- Characterization, features, Inspiration; the primary roles of performance amusement and black comedy.

- Published campaign packs: abominations, especially Waterdeep, which I regard as one of the worst things masquerading as a setting that I have ever seen, in concept, design, implementation, and experience.

- Good-hearted play full of humor, characterization as enjoyment, and general attention to the imagined fiction, i.e., no Murk. But toward what end?

- Everyone except me already knew exactly what the plot and back-story were, even Erik, who had picked up everything through his perusal of D&D texts over the past year or two, and even I had reluctantly picked up enough through previous encounters with the setting to recognize everything.

- Consider the necessary shutdowns of Erik’s spontaneous play moments, and that I’m the one who does it.

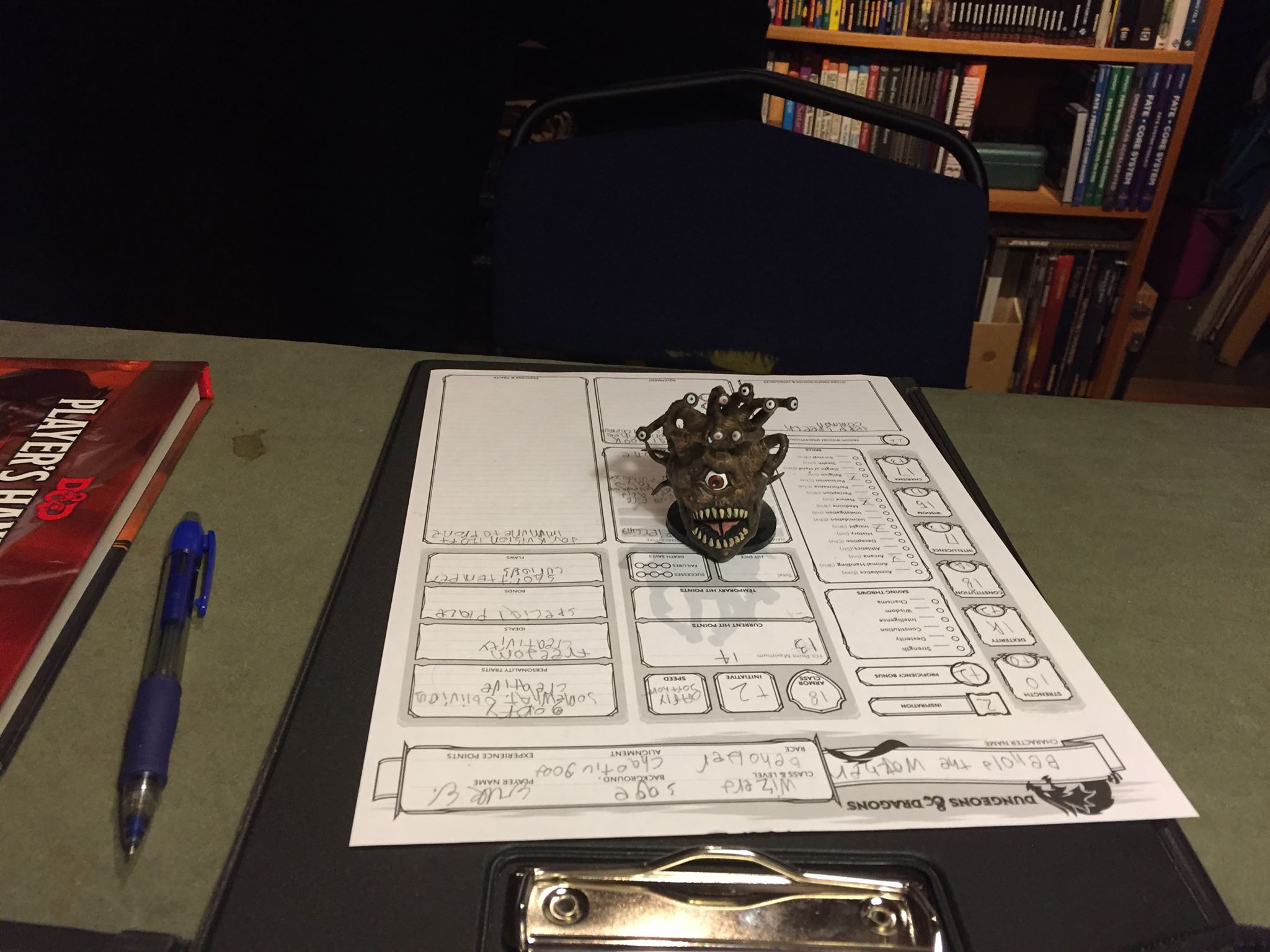

So, let’s see … we played the probably very familiar first session of the Waterdeep campaign as published for this edition. I have not included our character creation, although I might do so in the comments if I get the chance to finish editing it. The different characters’ features (background, flaw, etc) were the primary point of attention, including Erik’s beholder. He had originally wanted to play it as an NPC or monster as Ulf’s “assistant,” but shifted it to be a player-character along the way.

Franke made up an elderly wizard, profoundly bookish with a nominal lust for knowledge, but who evolved immediately in play into a dodderer, although not quite a dotard. Andreas made up a dwarven fighter named Bob, played as a kick-it-in bad-ass, and, apropos of the Monday Lab: Halfbreed discussion, I made up my half-orc rogue Locinda II. When Alice arrived, she took up a sheet that she had played before, a slightly disturbing log-lady sort of elf cleric.

So: a fighter, a rogue, a wizard, and a cleric; respectively, a dwarf, a half-orc, a human, and an elf. And then there’s Erik’s beholder, named Behold, who is very much his player-avatar in terms of personality. This emergent setup did remind me strongly of the late-70s old days, in its familiar array of race and class options + one person who insists on a monster character.

I stress that everyone played these very quirky and potentially anarchic characters neatly in tune with scenario-provided objectives and party togetherness. That’s worth discussing too.

- Part 1 (embedded below) combines or sort of trades-off between “how we know each other” as the end of character creation and “you’re in the tavern when a guy comes up” as the start of the adventure

- Part 2 is our “let’s go and do this” moment, introducing Alice’s character and also featuring my character’s solo venture to expedite the clue-finding

- Part 3 is the other characters’ visit to the Purple Curiosity Shoppe or whatever it’s called

- Part 4 is “this must be the place” and a little bit of tactical fight-starting

- Part 5 is fighting and magic! We all get to roll things and do stuff.

- Part 6 is fighting and magic too! Pay attention to the failed roll for my stunt.

- Part 7 finishes the fight and gathers the odd clue

- Part 8 is mostly decompression, acknowledging bit by bit that we’re done, and resource management

The session was well above the gold standard for good will, attention to the imagined situation, energy and appreciation toward one another’s characters, general following of mechanics and system options, and a nice combination of low humor plus self-awareness of it. I thank Ulf and everyone else greatly for their hospitality and welcoming attitude for Erik.

That said …

This game is caught like a writhing insect in The Impossible Thing Before Breakfast. If I play my character, in the sense of all this characterization and agency that the creation process fires up, then the DM cannot create the story, which is what everything about DMing and especially the published scenarios and campaigns emphasizes. And vice versa, perhaps especially, vice versa.

To unpack that: everything for the player presumes a DM who isn’t actually the DM as written/encouraged, and everything for the DM presumes players who aren’t actually those players as written/encouraged.

For long-term or naively text-trusting play, the group must pick one or the other, and ignore, as in obviate, reject, abandon, defy, reverse the text and most of the rules concerning the one you didn’t pick. Given effective and good-willed play using a firmly-plotted campaign pack (as we have in this case), the net effect is always the same: the players are reduced to posturing, establishing and repeating tropes, and (eventually) goofing in order to enjoy themselves, as the DM waltzes them through fights that lead to clues, and clues that lead to fights.

But that solution founders given even the slightest confusion about which side to diminish into mere colorful performance, which itself then turns into raw agenda clash about relative power at the table. Therefore the more usual outcome is to play into roadblocks of sudden disappointment or frustration, while insisting loudly online that this is the most awesome thing ever, then to limp along wondering about or resigned to the necessary outcomes of the Impossible Thing, and eventually to shift into lonely fun with one’s extremely expensive purchases.

18 responses to “Behold 5th edition”

Directed vs. Emergent Play

I agree with your premise that the Players Handbook and "How you build your character and how you play" has very little (or nothing) to do with the way the DM is tought to do their job. (I'm using "their" and/or "they" in third person singular here to avoid any gender-discussion, hope that's ok.)

I agreew that in a sense these two are on oposite ends of a spectrum where player freedom is more limited to closer to DM teling their story you go.

I'm not sure I agree with the somewhat (imo) hyperbole conclusion that these two can never meet. The way you describe it makes me think you see this in absolutes. Black and white. It's one way or the other. If that is the case (I'm leaving the possibility of me missreading this, open here) Then I do not agree. I think there are infinite ways to find a compromise and end up at any give intersection somewhere between these two abolutes and mutually exclusive end points.

In fact I think very few of us pla exclusively in one or the other, but somewhere in between. Some games are very far towards one or the other "pole" but there are always boundrays.

I would like to point out that both DM guide and the published adventures have a lot of guidance for character building. Suggestions if you will, about how to create a more invested character. It's not perfect, and it's not enforced but it's probably better than what we did, which was basically just "jump right in and create whatever character you want. (which, granted is what the PHB says you should.)

In a published campaign the creative freedom of the Player is limited. That is true. Most of the time it's going to be a railroaded journey. Maybe there's some options here or there and maybe we can go along side the tracks for a while, but the track are there in 90% of the cases. But the freedom is not completely gone. You can still choose and play and improvise around these tracks, inside the boundray that the campaign set up. So it's far from nullified IMO. The question then becomes what sort of freedom do you as a player evaluate. What is important to you. That will guide where you would like to end up on this sliding scale.

Not sure where I was going with this, but I wanted to get it out. 🙂

/ulf

A video response will arrive

A video response will arrive soon!

[edit: having software troubles. It's filmed but not ready yet!]

I enjoyed listening to this,

I enjoyed listening to this, even when the all-too-familiar D&D issues (e.g., "do we kill or take prisoners?") cropped up. Thanks!

It's a bit hard to know when the kid-attention/parental-supervision issues kick in vs. game-play/game-design, but it is fascinating to see in actual play how natural and spontaneous it is to narrate outcomes and create backstory, even when it may not fit the game system and/or play context. Maybe it's just obvious that managing that process is always neccessary, and simple management is easier, but whatever game design impulses I've indulged are probably motivated by wanting more complex management that is … engaging rather than distracting?

On 5e, my direct experience is minimal – for "D&D" (fantasy informed by some stripe of D&D influence), the various 3e rulesets have served fine (mostly Pathfinder, with the HeroLab software really required, especially when I GM). But it certainly seems like in any "D&D" the Impossible Thing demands attention, and I don't know exactly how to articulate when it's avoidable and when it becomes unresolvable. I feel like it's something I and those I play with have had to learn how to manage in order to get the play enjoyment we want, but detail … I'm inarticulate. I look forward to the video reply to Ulf. I do think, though, that "use the texts from the basic books as purely as possible along with following an introductory module closely" is a definite worst-case, actually black and white situation.

Inspiration also seems worth a deep look. Be it Fan Mail or FATE Points or whatever, these apparently-similar kinds of rewards seem both powerful and easy to muddy/misuse, in any or all of creative, social, mechanical, and mathematical ways. And I'm not sure how much that depends on the NOT-actually similar details vs. other factors (inherent, or maybe agenda-connected).

Sorry for the delay! I had

Sorry for the delay! I had audio issues, but here it is: Response to Ulf.

One clarification:

One clarification:

When you say that the game isn't OSR but Fudge, are you saying that 5e moves away from a cogent, tight system to something more freeform and amorphous?

I'm interested in this discussion, which touches on issues of player agency, narrative creation, social validation at the table, and integrity of play. I will make some time to watch the "Plot Thickens" workshop, and it looks like "Roll to Know" might also be worthwhile.

One issue that I'd like to get a more clear bead on is the source (or sources) of what you term control. Control can be a result of a forceful GM, a play culture at the table, a general play culture, a scenario or campaign, or the rules themselves. In the most immediate occasion that sparked this discussion, it seems like Waterdeep is the main culprit, but I would imagine there are other factors at work, not the least of which is the entrenched mindset that some games engender.

Though I don't play D&D too often, I would say that, when I sit down at the table with that game, I expect there to be a certain level (maybe even a high level) of control to be exerted. I also recognize that there is a general appeal for that type of play. With a pre-written D&D scenario, everyone around the table can relax and have a communal story-reading experience where you get to inject some limited color in the planned adventure. Sales and popularity have shown that there is a huge market for that type of approach.

At one point in the video you talked about the way that control can, in some situations, trump the system. But in some cases, the system itself can enforce (or encourage) control. I've not played Gumshoe, but from my understanding of that system, the rules are set up so that players get the clues they need to take them along the plot (which implies that the system has a plot in mind). Again, I think I could enjoy playing a Gumshoe game, though I know the expectation would be for me as a player to follow the breadcrumbs leading to a designated final encounter or revelation. That could be fun if it was an interesting story, but it certainly would mean strict limitations on collaborative creativity at the table.

The case of control in D&D 5e seems more murky. There's obviously a sizeable play culture that enjoys a high level of control in their games, though they wouldn't necessarily admit to this. (Kind of like the case study of coffee drinkers: Many will tell you that they like a bold, robust roast, but in terms of actual blind taste tests, they prefer a smooth, light roast.). It would be an interesting task to assess the degree to which this control has become baked into the system itself, and also to do some study of the popular published campaigns and scenarios to see how they dictate control.

One experiment I've been thinking about running: I'd like to go back to Holmes and one of the Basic Modules, and then work through Moldvay, Mentzer, and then AD&D (along with some of the key modules) to get a better handle myself on these issues of player agency, control, narrative emergence, etc. as they developed through the different versions of the game. That experiment would take some months to complete, but it would be illuminating (not to mention the fact that it would refresh my memory and fill in some gaping holes in my knowledge of early rpgs). It might even be interesting to run those games with an impish eye aimed specifically at avoiding or dismantling control situations (such as when a module or scenario nervously tries to give the GM advice for railroading the plot) while nonetheless staying within the system.

Hi Robbie,

Hi Robbie,

Here’s a crucial point: the control that I’m talking about, by which I mean an interventionist or override-type control “move,” is strictly an issue of play, and of group concession rather than resistance during play.

[Minor clarification: we’ve been focusing on the GM as acting-perpetrator, and we can stay with that, but the topic is the same when it’s traded around, or more likely, competed over.]

Therefore, it does not matter whether:

All of those are merely means to the basic fact of whether it’s being done in play.

You’re right that these distinctions aren’t trivial in terms of a single group and its experience of play. But I argue that they are trivial in terms of a given person learning how to play, because that learning will take place via the examples, instructions, and modeling-actions and responses of the other people at a table, not via a core rules text.

With that in mind, you are totally right in looking at the adventure or scenario texts, because, as I’ve been describing for some time, they are historically the actual learning texts, far more important than core rules. I am certain that whole play-cultures or communities have hardly ever ventured away from these.

The main insight I offer about these texts from the late 70s through the late 80s, and I suggest you consider this when you examine them, is that they were not created as authored publications, but as practitioners’ devices for convention play. They carry with them several features because of that:

These arose mainly in RPGA play around 1980, especially as refined and modeled by Frank Mentzer (e.g. the R series), and swiftly became the standard (the L and N series). I talk about them in detail in my “orthodoxy” video about D&D as a religion, Finding D&D: Communion, especially in contrast to the competitive tournament scenarios which had to be rewritten to seem as if they were story-ish or saga-ish events (e.g. the G and A series).

Regarding the comparison you’re talking about, be very careful about dates. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, for instance, was created and published in full parallel with and therefore does not succeed the Holmes, Moldvay, and Mentzer sequence. That is, “Basic” was not created and played before “Advanced.” I have a handy diagram to help with that.

I agree! That is what my game Elfs is for, absolutely, and nothing but, that exact question cast into the mechanics of play.

The reference to Fudge

I’m pulling this part of Robbie’s comment into its own thread.

I can’t understand the question; it explodes into an endless quest for what you mean and why/how its parts are arranged.

For one thing, I don’t think those four terms’ content are clear enough to use easily. I have no idea what “tight” means, for example. They are also heavily loaded with judgment, even if you personally aren’t including any, and their dichotomy (as you’ve phrased it) is not justified.

More important, which RPG titles qualify for the terms’ application is evidently a matter of identification, loyalty, and uncritical labeling rather than anything worth attention.

For example, even if we broaden one of them, “freeform,” to the most general possible meaning, then I’ve still seen it applied in the craziest ways, e.g., to Sorcerer, which is anything but. Also for example, by that same most-general definition, that term applies to combat narration in every version of D&D except for 4th, and yet this title, except 4th, is often held up as the standard for the most “solid,” or “non-freeform” reference.

Or “tight,” which you are (I think) associating with OSR/D&D – yet it’s axiomatic among OSR discussions to present the interpretable aspects of the text as the virtue of old-school play, the whole “rulings not rules” phrasing.

I don’t think I’m merely quibbling over phrasing. I think those terms are pure poison in isolation, that your association of OSR with tight/cogent and Fudge with freeform/amorphous makes little or no sense to me, and that my reference to Fudge has nothing to do with any of the four terms by any definition that I can imagine.

So the answer is “no” on many levels, most of those levels involve attacking the question. The only question I can actually answer would be, “can you unpack your reference to Fudge?”

My answer to that is that I was referencing:

Thank you for taking time to

Thank you for taking time to reply. And it was a good one. I mostly agree with your assessment. So let's break it down a little to see where I have reservations, and there are in principle two of them.

1. Social Dysfunction: The kind of objections some players exert over other players, or peer-pressure, or as Maria sometimes call it; right out fear of being "wrong" or doing something "stupid", that you talk about initially is a real thing. Thought it would be interesting to try a game system that claims to "fix" that problem I'm not sure there is one. At least I have yet to play one. This type of issues should (IMO) be adressed socially. Talk it out, make people aware, be more sensitive and ask players what they think. All of that. Maria is convinced this problem would still be there for her no matter what game she played, because to her it relates to "who" she plays with and if she is more alligned with them. You know; Do they interupt me all the time? Do they roll their eyes when I suggest something? Do they sigh and shake their head? Do they laugh? How do they laugh? etc. Some games might be more attentive to this sort of problems and talk about them, maybe even be more conductive to mitigate them, I don't know, but fixing them? No I find that hard to believe. DnD spends very little time talking about these issues, for sure, so it's probably at the bottom of the barrel.

2. Plot is not all there is to Role Playing: Focusing on "plot" only almost takes away too much of what the RPG experience is to even be a meaningfull exercise. And even if I can still argue there are hybrids out there where DM has majority of control of the plot but players can inject plot changes here or there by using the system (13th Age Glorantha rune narration for instance). I'm not sure it matters to me. As I said in my original post, even if the railroad-tracks are still there you can always play "around them". So again I think it comes down to what "fits" the player the best. Using Maria again, she claims she would love to try the other end of the spectrum, and think s it might fit her better, but she's still convinced that Problem 1 above would not change. Where as Bob (player in our group) is all about uncovering the mystery that I (the GM) have put before him. Any Player input into the plot would be breaking the "illusion" that there is a mystery to solve here and kills the enjoyment for him. He has zero interest in participating creatively in building up the "plot".

I saw the other video reply you put up yesterday and want to draw a parallel here if I may, because I think it might be a useful example:

You talk about how people sometimes think you are a genius for coming up with plot when in fact there was no hidden strings being pulled… (I can't remember the exact wording but you get the idea) and you have to convince them that in fact this was just the game being played and it just happened (sort of). Some players (like Bob) would liken that to a stage magician showing how his tricks are made, and in so doing RUIN THE WHOLE THING! 🙂

I've been there as a GM. And I would NEVER admit to just making shit up, because it robs those players of the sense of wonder, connectiveness and magic that they feel, AND (and this might be the most important part) that they would NEVER feel if they took part in creating the secrets themselves. (Well actually I DID admit it a couple of years after the campaign closed out, but hey… :-)).

Some players just want to solve the puzzle, not create it.

The question then (for me) comes back to problem 1 above; How do we allign ourselves socially, so that Bob can solve his puzzles without calling Maria stupid. How can we give each player what they want out of the experience without stepping on any toes and keep everyone happy?

The comments have become a

The comments have become a little messy (even though I tried to separate them a little), so although this is directed to Ulf, most of what I’m saying here applies to Robbie’s points as well.

Also, in advance, and by request, I want to get into more of a dialogue, where I am asking questions and not presenting so much as lecturer or “source,” but this post is still in that mode. I will shift out of it from this point forward, I promise.

I want to pull apart some different variables in this conversation.

Content

One of them is the prepared material or back-story, or content that is known by one person (let’s stay with “GM” for simplicity) and is treated as “real” in play even before other people know about it. An obvious example is a map that describes where our characters are, especially when the complete one is known in detail only to one person, and the players have or make a limited version.

Similar material includes who killed the butler (maybe it was the butler!), or where the kidnapped person is, or whose wicked plans have indirectly caused the problem or situation that our characters encounter. All of these things, because they are prepared and established as having occurred, are now relevant to what is occurring now as far as our characters are concerned.

I want to eliminate the technique of improvising this kind of information during play. That isn’t involved in what I wrote in the post or said in the videos here, or in Robbie’s Sorcerer post. For purposes of this conversation, let’s take it as given that plenty of information has been created, noted, and prepared for purposes of playing this session, and it will not be altered or replaced during play itself. Let’s also take it as given that one person has established it and the other people playing don’t know important parts of it at the start.

Dysfunction

These issues brought up regarding Bob and Maria can be pretty deep and depend greatly on the specific point of disconnection.

If they are both invested in discovering the thing, then they may differ regarding “how we discover it,” especially in reference to investigation or clues. To pick examples based on my own experience, one person may see clues as signposts or relatively pro forma “steps,” and the other may see them as a genuine puzzle which may be solved or failed. Or they may both care about solving clues, but one may treat the clues as character roll-based challenges and the other as personal cognitive challenges.

If they aren’t both invested in “whether we discover it,” then one will be unhappy or bored with the other (or both will) for trying or not trying to do that. Again, as an experiential example, one may be more invested in the developments and changes in relationships with the NPCs who instigated the situation, treating the mystery or puzzle as a means to that end, and the other may be invested exactly the other way around. These are more profound differences than merely “style,” because they interfere with enjoying what one another is doing, and platitudes like “don’t be a dick” or “everyone can appreciate everyone’s fun” do not work at this level, because no one is wrong.

If that unhappiness is expressed in rude or dismissive or snarky ways, then this disconnected goal now becomes a genuine problem among real people. At this point I have to step away from any reference to the actual Bob or Maria even by inference or comparison with my own experience; once interactions have moved into explicit socializing and even ethics, they cannot be addressed in terms of game design or modes of play.

I’m proceeding with our conversation about the Impossible Thing with those two issues set out of the way. 1. We know information and situational problems are “fixed” as far as preparing for play is concerned, i.e. the GM isn’t winging things like who killed the butler and we aren’t using any kind of system like “you rolled enough successes, you say who killed the butler.” 2. We are also playing with, and as, people who are creatively and procedurally compatible, in fact, more than merely compatible, because we enjoy the way we do it together.

My topic

So, let’s consider, “how we discover it” or more sensitively, “whether we discover it when we try,” or most sensitively, “whether we prioritize something else, as things proceed.”

Looking at the bits of play involved in these things, I see how situations are presented (or “arrive” or “are found”); how stated actions are received; and, if accepted and resolved, what their outcomes accomplish.

Here is where I am proposing The Impossible Thing, that there are two approaches to how this is done.

State 1: it is useful to think of this as a funnel, getting narrower and narrower.

State 2: it is useful to think of this as a pump, proceeding from a pressurized position into a unique and unplanned circumstance.

You can probably easily see that we could be talking either about mystery/discovery scenarios or about a more straightforward “find villain, stop villain” combat scenario. It doesn’t matter which.

I also suggest that fudging or messing with mechanical outcomes is very common in playing State 1, and very uncommon, even absent, in playing State 2.

It may be hard to believe, but I am not presenting these as good vs. bad play. I know which I prefer but you saw me play State 1 perfectly cooperatively during this game. My point, "the Impossible Thing," is structural, not judgmental: that there is no compatibility between them in play, despite the incredible diversity of techniques and goals that may be in place for either one.

I’m generally reluctant to

I'm generally reluctant to declare absolutey that two positions are mutually exclusive. So, I would need more time before declaring that State 1 and State 2 are always and everywhere incompatible. That said, I do find Ron's post to be on point and helpful in clarifying goals and approaches to play.

To help me get a handle on this, I went searching for an analogy. As with all analogies, this one does break down, but I think it might have some use. The analogy comes from the realm of video games.

State 1 analogy: Video games feature a prescribed narrative and/or goal of play, and there usually follows an idea that there is a "right way" to play the game and that one's merit is determined by how well one is able to manipulate the game inputs to achieve the preestablished goal. There can be side-quests, easter eggs, and other surprises offerred to the player, but that seeming flexibility doesn't alter the basic goal that is established, and the game can, in fact, force the player down a track. I want my avatar to go into the forest, for example, but I might have to first unlock that area by doing something else first (otherwise, you see your avater endlessly running against a silly invisible wall). If you play the game in the way it is supposed to be played. you are in State 1.

State 2 analogy: But the same video game could be used for other goals. For example, I might use it to make a machinima film: That is, I could use the resources of the game and the same input devices to provide animation for a movie detached from the intended goal or plot of the game. I might use Halo, for example, to explore a story about the price of war and the virtues of diplomatic solutions. There would be times when I would be following along with the game's narrative to get me to a desired setting or NPC encounter. I might even include instances of straight game play in my movie. But my goal and drive would be very different. Here, I would be playing in something analogous to State 2. I'm playing Halo, but doing so in a way that would be fundamentally incompatible with the way a player in State 1 is playing. (State 2 is not confined to machinima. For example, maybe two players decide each time they sit down to establish a different objectives during game play.)

Obviously, if a State 1 Player and State 2 Player got together for a game of Halo and both insisted on playing the game according to their desires, that would be a dysfunctional situation. The analogy makes clear that this is something that is being done in play and that's what makes the crucial difference.

Thinking about my analogy also has brought into focus (for me, at least) the issue of economics. If you were to ask the video game company or the rpg company producing modules which of the two States of Play is more lucrative, the answer would have to be a univocal answer: State 1. The reason: If players are convinced that State 1 is the way to play, then, once they have achieved the end of the narrative, they are more likely to go off seeking the next scenario or campaign to follow another story. With State 2, the possibilities are more open-ended and multiplicitous, and if the players were interested in following out the trajectory of an unplanned story created during game play, buying another scenario/campaign might, in fact, run counter to the direction of play they initiated.

I’m really interested in the

I'm really interested in the issues raised here, but I've always found them very hard to talk about. Hopefully this discussion will help me find ways to productively engage with 'em, so already – thanks, all!

Trying to stay within this subthread… Ulf, I'm very sympathetic to the concerns you describe from Maria – I've definitely played with folks with those concerns. All I've figured out so far (and I think this is covered by what Ron said) is: not liking how someone is playing, or how someone is expressing unhappiness with how you're playing, is a social possibility regardless. Which is not to say there's NOTHING in game design and/or how we play the game that influences how those concerns happen or how likely they are to happen. The hope would be that understanding how State 1 and State 2 don't work together is helpful – maybe VERY helpful for some people in some situations – but that's it.

Ron, in your response, it's probably no surprise I'm quite sympathetic to your "no compatibility between them in play" statement. But rigorously understanding just exactly what the "them" is has proven a bit tricky.

I'm a little uncertain about "I want to eliminate the technique of improvising this kind of information during play." On the one hand – sure, yes, I agree, often you can easily identify improvising vs. not, and eliminating that in this analysis makes sense. On the other … the context of how/when a piece of information is introduced/revealed in play is kinda always (in both States) "improvised" in some sense, isn't it? I think you can still identify different ways that happens, from just the unavoidable (and hopefully appropriately-reasoned) consequence of the GM's (let’s say) decision, to picking a context that changes the impact of the information SO much it might just as well be made up on the spot. But maybe that kind of subtlety isn't important just yet, if at all.

I also wonder about the … scope? of constraint on stated actions. Certainly I agree that in State 2 compatibility with planned "next steps" can't be a factor, but … let's say it's clear (for e.g.) that for some session(s) play is going to be about what's happening in a particular region, and therefore actions that ignore the region and send everyone home to spend time with their family instead would be unwelcome. Does that mere "it's clear" put us into State 1? If not, what amount/types of that sort of thing can you have and still be in State 2?

Robowist … I'd want to keep State 1 and State 2 just within the gameplay itself, not using the gameplay to build a new thing. That said, and allowing as you do for the roughness of analogy, I think computer games that can in themselves be played in both of State 1 and State 2 do exist – going way back, there's something like Ultima IV (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultima_IV:_Quest_of_the_Avatar). The Stage 2 "wave front" of what happens next (to use Ron's description) is limited by the data and algorithms implemented, sure (roughness of analogy), but if they've been implemented at all, players might either be attentive to the available wavefront – or not.

Let’s see if this reply ends

Let’s see if this reply ends up where I hope it will. Apologies in advance if it doesn’t.

Ron; your State 1 and State 2 clarifications (along with the stated assumptions) makes perfect sense to me now. And I can see how theyr are incompatible, but only in each instance of play. Surely the could swap in and out for certain scenes and chapters of the story. In fatc the campaign we started in our session has a completely different structure in Chapeter 2.

Chapter 1 ends with the PCs receiving payment in the form of a piece of realestate. An old Inn called Troll Skull Manor in a rather posh part of town. Chapter 2 is all about moving in, getting to know the neighbors, deciding if you want to start running a business together, being approached by different guilds and factions in the city that want to recruit a PC etc. The chapter has no event order at all. But instead sports maybe 20 different suggestions as to what could happen. I can se that chapter being run very much as a State 2, even if the first one was clearly written as a State 1.

A few ideas in response to

A few ideas in response to the thoughts about social dysfunction (maybe too harsh a word) and plot:

The Social Dynamic

For the purposes of discussion, it seems like we can set aside those parts of games where a turn order is established or when players are explicitly given authority to make a decision. Rules governing combat and character creation are instances: If the rules dictate that it is Player A's turn to take an action during a skirmish, then for another player to infringe upon that choice is out of order.

But that leaves the vast space in the game where a complex social dynamic is involved. A few practices that have been helpful to me.

Plot

Variety of styles and interests among players is a positive, but there are limits. Here again, some type of preliminary discussion before play is useful: It gives everyone around the table a sense of what the purpose of the game is and what they should be aiming for, and makes it easier to identify types of play are out of bounds. If you have a player like Maria, you could explicitly set up parameters to encourage her input (and likewise you could put players like Bob on notice).

In terms of the idea of mystery in a game, there is a vast and fertile middle ground between the "railroading" and the "making up shit" approaches. As a GM, I enjoy creating conflicts or situations on the fly, but the best of those involve playing with elements that have already been introduced in the game or which have been mentioned by other players. The experience of players like Bob, who would find his enjoyment lessened if he knew where the ideas came from, is curious to me. I suppose if I had someone like that, I would simply not tell them what I had planned ahead of time and what I came up with at the table. Let him live in blissful ignorance.

One set of terms has been rattling around in my head during this exchange. Michel de Certeau's "Practice of Everyday Life" employs the concepts of "strategy" and "tactics" which might be useful in this discussion. Here's a quick summary of what de Certeau means by those terms:

So, in the field of rpgs, a pre-packaged plot provided by a module, campaign, or scenario would count as a strategy, whereas those often creative and ingenious ways in which individuals play with and tinker within that plot would count as tactics. De Certeau suggests that there is both a strong motivation and a pleasure derived from engaging in tactics. Granted, the control elements of strategy are still in place, but the implementation of tactics creates places where one can explore, have fun, and even create small places of freedom and revolution.

[p.s. Ron: Thanks for clarifying the comment about OSR and Fudge. You could tell by my fumbled question that I was befuddled.]

For reasons unknown the

For reasons unknown the comment section here is very "shuffled" and presented out of order now and I can't reallt follow who is replying to what anymore. Sorry.

Robbie made a comment about Bob's unwillingness to see behind the curtain taht I think deserves a reply though:

You said; "I suppose if I had someone like that, I would simply not tell them what I had planned ahead of time and what I came up with at the table. Let him live in blissful ignorance."

I… don't follow… First off. Yes that is how he would like it to be handled, but secondly; that solution implies you actually HAVE a plan to hide, right? Whether it is pre-written or whether it is made up by yourself before hand makes little difference in our discussion, I think. Either way he would be fine playing as long as he did not know what it was up front. He wants to discover it during play, and he needs to have a sense of "treasure hunting". This would be completely lost if he himself was expected to provide his own puzzle, or even give input to one. That's the problem he wants the GM in Control of that.

Hi Ulf, I will email you to

Hi Ulf, I will email you to explain how comments are nested. However, I also decided that Robbie's post needed to become its own topic rather than a reply, so I have pulled it into "titled" status and included your reply to it.

I need to return to this later

It's worn me out. I've spent over twenty-five hours of direct effort on this discussion so far, and every step seems harder. I will try to make two small points, and after that, please keep discussing things with one another. It will probably go well, or better.

1. To Gordon, by "eliminate" improvised material, I mean strictly for purposes of this conversation because for this topic it's a red herring. I'm not talking about eliminating it from the hobby, from play, from consideration in the long run, or anything else.

2. To Ulf, yes, per instance of play. That's exactly what I'm talking about.

Thanks to everyone for the attention and interest.

Ron – Understood, and cool by

Ron – Understood, and cool by me! I didn't think you were ignoring improvised material altogether, but I'm maybe not so clear how/why it's entirely a red herring in this conversation. But I certainly see SOME ways in which it is, so it seems fine to leave it there. I've got one thing to present and see if anyone has comments, but it may take me a day or two to pull together.

That I've been in Ulf's position (running D&Dish play for friends and their children) a fair amount recently no doubt makes this context especially interesting to me. As always (as in, for a decade +), I'm shocked at how hard this stuff is to talk about, and feel very appreciative of everyone who tries – here, specifically, you, Ulf and robowist. Thanks!

I apreciate the siscussion

I apreciate the siscussion and everyones inputs.

I have to say though that once we get down to “instamce of play” it more becomes a question of how a particular campaign is written and less about pre-written campaigns in general, or even worse (wirse as in broader brush) an entire game.

I’m okay with that. 🙂

/ulf