This is the single most brutal post I have presented or perhaps ever will present at Adept Play. So I’ll start with all the good things.

The fictional adventure as atmosphere and topic was delightful. I offered a starting point which instantly became, from and for everyone, absolutely our own mostly-anthropomorphic frog fantasy. Lorenzo rightly pointed out that it has some affinity with The Wind in the Willows, if you can imagine that with a sprightly, audacious, sword-and-sorcery spin. I’ve included the initial handout, the map for the village of Wambaroum (the same as used for a very different community in the Whimsical Ways game), scans of my very messy inter-session notes, the characters’ initial sheets, and the final story/sheets for two of them.

At about this point, you should probably embark on the videos. They include my summary of the first session and discussions or reflections that we happened to get into as a starting point for each session, and the whole thing finishes with a discussion as well.

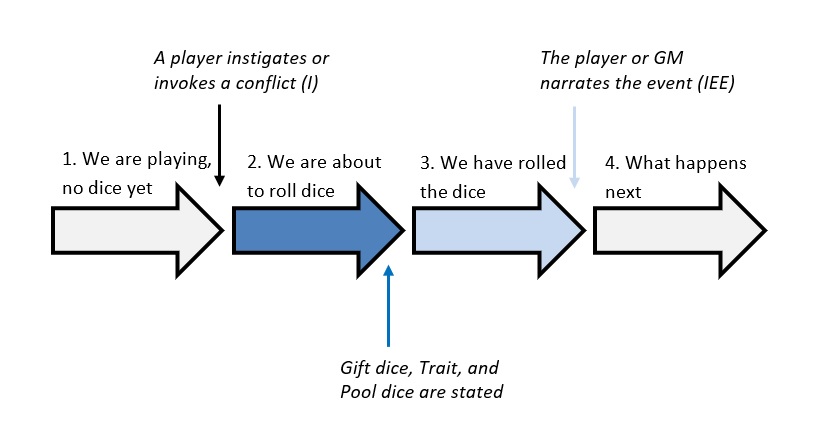

I don’t even want to go into how absurdly fraught all discourse about and reference to The Pool began and has remained. It is twenty years of stinking, fetid mass. Instead, I want you to work with me de novo, regarding this diagram.

I designed it very carefully. Here are some details to spot right away.

- The vertical arrows do not point at the junctures among the big arrows. They point at the big arrowheads, meaning, the activities inside the main body of each big arrow have resulted in the events described in the italics. Therefore the big arrowheads are the locations/positions of the procedures of those events. That’s why the vertical arrows are colored-coded to the big arrows, too.

- The procedures in the italics are specific to The Pool. The conditions or status of play represented by the big horizontal arrows are not specific to The Pool.

With me, still? The first point for this post is that the problems in playing The Pool are not located in its procedures and the vertical arrows. They are located in the big arrows. The virtue and curse of The Pool is that playing it reveals – with surgical and terrifying precision – exactly what the people playing are bad at in those big arrows, in their general role-playing.

There is no way to engage with this issue without triggering a round of excuses and defenses. Therefore, I’ll start with my own examples which you can see nicely in the videos, and which I’m summarizing here in the form of “You suck at this, Ron, this is ‘notes to self,’ so pay attention.”

- Not being absolutely hard-ass about establishing that once we are in the blue arrow, there is to be no take-backs and re-framing of the preceding grey arrow, which includes the established reason and purpose of the conflict-and-hand.

- Not explicitly transitioning into the fourth big arrow, i.e., making sure that we all (and especially the concerned player) get out of the narrated outcome and into a New Now. This arrow is grey like the first arrow because it has the same internal arrangement of authorities and procedures, e.g., no dice are involved … but it cannot merely be stuck in the same fiction of the first big arrow. In fact, this applies especially when this new arrow is entirely continuous with the old one in terms of time and space, i.e., when its initiation, post-narration, is not a scene transition.

Now for the harder part to post about: that GMing this game with Manu, Claudio, and Lorenzo was frustrating and absolutely exhausting for me. I had to re-orient play at each big arrowhead again and again, and at least half the time, I simply threw up my hands in despair and applied the procedure with a sledgehammer just to get through it. By the end of each session, I forgot or even forgot to look up procedures out of sheer fatigue. In each session, I can point to one moment in which I almost simply closed out the entirety of play and said, “I cannot keep doing this, go home, we are done.”>

Keeping in mind that some of what I’m describing next is codependent with my own failings described above, what do I mean?

- They clarify and explore what their character thinks or knows or wants, without stating actions that do something; this is often stated to prompt me to decide what happens instead of doing a thing.

- Closing off options or narrations with “I can’t,” including but not limited to claiming Traits don’t apply when they often obviously do or could. “This is a situation I can’t escape from, and I understand that you mean it that way …” “I can’t kill the snake …” “I could do it if I weren’t looking for Urrop …”

- Jumping ahead of the roll based on anything I say to clarify what others are doing, as if it had been an outcome, especially assuming that it blocks or nullifies what they said they were doing, and then responding with a new action.

- Asking for clarifications or making statements in a weird way, to frame/influence the situation outside of their authority, including but not limited to what NPCs want or know, including posing hypotheticals.

- Stopping short of closing the conflict completely when taking the monologue of victory, i.e., not getting the conflict decisively done and described, forcing me to finish these narrations for them.

All right, calm down. I’m not blindsiding my fellow players or calling them out. We talked about all these things in the recorded discussions, so you can see everyone’s perspectives and clarifications. I anticipate that people reading this will leap to their defense – few things are as reflexive as gamers making excuses for one another – so please don’t do it. They’re fine; I am not hurting anyone.

Please consider, too, that each person is distinctively almost-always the GM when they play; in fact, I’m pretty sure that they haven’t played as non-GMs for years, except with me here in events via Adept Play. What that means to me is that their player-habits are far less self-monitored or easily-recognized or reconsidered in the moment than their skills and habits as GMs. I’ve caught them outside their comfort zones. I bring this up not as blame but as caution to every other person reading this: who are you, when you are not GMing? Are you sure you know?

Here’s my big goal for posting. There is too much blither and anxiety about the specific procedures of The Pool, and not enough attention to and reflection about the basics of play. E.g., how are authorities distributed within each big arrow, how do we know when we are starting a new big arrow and what do we do at that point, and how to be/play within each big arrow, for itself, without being stuck in the old one, without going backwards inside this one, and without trying to massage or set up for the next one. And very, very specifically: without trying to be a “good player” who is facilitating the GM’s presumed control of the current arrow and presumed setup for the next one.

These are questions for any and every role-playing game, or more accurately, for how you personally play any given role-playing game. Until you really dig into this topic of the big horizontal arrows, about yourself, then every single bit of attention you pay and analysis or debate you enter into (including design) regarding any given game’s small vertical arrows is deflection. You’re hiding behind them.

With me, still? Probably not … The Pool’s virtue and curse, as I say, is not that it’s problematic or difficult – it’s that the basics are completely ordinary and its specific procedures actually work. Therefore playing it does not need, nor even permits, the constant adjustments, elisions, and fakery which almost always pervade people’s habits of play. I go so far as to say that people actively distort and problematize The Pool as such, especially procedures like the Monologue of Victory, in order to avoid confronting this fact.

This is why I’d actually rather not, at this point, see comments about our thoughts and conversation for The Pool itself, such as the question of whether to provide new Pool dice at the start of each session, or whether and how to add your new words for every session, or whether there’s a death spiral, et cetera. All of those are important – but I perceive that discussion as another comfort zone, a way to yip and yap and deflect. I’m only going to talk about them with people who have been through the harder work first.

29 responses to “Frog Pool fantasy”

Not that brutal, and appreciated

It must be my personality or being neurodivergent, but I 100% appreciate this kind of feedback — even the parts I disagree with or have a different view on — and that's exactly why I come here. I would have found it more offensive if stuff like this had gone unsaid. We now have a starting point for dialogue and better understanding what happened during play.

This hobby or creative endeavour is hard enough to grasp when we're not walking on eggshells to preserve people's feelings, saying "yeah, I had fun" after a mediocre session, like most people do. No-one learns anything and no-one improves. I second the feeling of not trying to jump to our "defense" — I pretty explicitly asked for this multiple times.

Regardless, I have a net positive outlook on the sessions, but it's totally understandable that for you the relative shift from your average quality of play was different than mine.

In the end, what you said here is more or less what we discussed in the debriefing of the last session, so nothing new — however I would encourage everyone to take a look at that video. I have a few comments that I will make here that will partially repeat some of what I said there, but it's a worthy listen anyways.

As a second thought, I didn’t

As a second thought, I didn't manage to emphasize enough in the comment above that I consider this kind of direct, honest, post-game feedback to be:

– The opposite of rude

– Helpful in every way

– Absolutely necessary to the continued enjoyment of this activity

Without, we can go back being force-fed pre-digested mass-consumption entertainment.

While I understand why you did write such a large disclaimer about tone, I wish the state of internet discourse was not such that you would feel the need to do so.

What I also see

First — fully agreed on points 1 and 2 regarding clarifying the procedures of play. I think the game would benefit from the "token" solution you suggested where you put a token on the table to signify that there is a pending roll. In fact, I'm thinking of many games that would benefit from something similar.

Regarding the player side, I think it would be more helpful if you specifically said which player in your opinion did what, but I understand you don't want to "call people out" individually — I, personally, would prefer you do, at least regarding the points that you feel apply to me, it just makes self-reflection easier.

I yet have to re-watch all of the videos — I'm pretty sure I won't have the energy to. I'll report my side of the points you raised, with no attempt of "excusing" but to explain my perception of them. If there's anything that I say here that contrasts a lot with the stuff on film, well, probably I will need to think about it.

1) I've a habit of stating my character's thoughts when I'm thinking aloud and trying to figure out their goals, and I'm not sure what they will do. This was never intended to prompt you to answer for me — I've pretty much never done this type of shit, ever, on any side of a gaming table. I don't think, at least for me, this happened as you've described.

2) I definitely see your point regarding closing off options, especially regarding my snake scene. It's a mixture of a couple of things.

– I perceived your statement about the snake going through the passage as "yeah, going through this is not going to be possible", as if it was something resolved and not uncertain. This is definitely not coherent with how the game actually works — either we've rolled on it, or if it's in the realm of possibility, I can call a roll on it. It's particularly strange and warrants some amount of thinking about.

– Not being able to kill the snake was more about "fuck, this thing is enormous and I just have a little knife and a bow and arrow". It just didn't feel right or sensible to attempt to do so — Woshi already got hurt, and he got the message the first time. I — Woshi — got scared! I didn't feel this character as particularly martial, and even if I could know the snake was killable through a conflict roll, he didn't. Woshi did what he did best — dodging around and getting the snake tangled up. I think this instance was productive and not what you're describing.

3) I didn't perceive myself doing this, but I might very well have — in several instances, resolution was unclear to me.

4) I'm pretty sure I didn't do this, not in a way that I was aware of. I definitely don't remember myself trying to suggest NPC feelings, goals or wants to you. You would have to point a moment out for me.

5) If I recall, the only MoV I took was the one where I tangled the snake up. I think I carried that through to the end of the conflict, no? You had to prompt me regarding what happens to the other people in the room that were escaping. I didn't perceive this as particularly problematic, just asking questions and clarifying what happens. Is your point that we had a different perception of what the stakes and scope of the conflict were?

Feel free to answer the individual points on separate comments, if you feel they're meaty enough.

Regarding the others, I have to say that I am struggling to remember how the resolution process went for rolls that didn't involve me. You may take it as another point of evidence that resolution was collapsing into murky diegetic soup with jumbled authorities.

I’m not interested in a

I'm not interested in a personal dissection for each player, or rather, I'm not interested in participating. This isn't a list of accusations to resolve forensically; it's a matter of watching yourself play and seeing what fits or what doesn't. This may sound harsh but I don't actually care whether you agree or disagree. I do care whether you reflect about it, to whatever conclusions you may draw on your own. I also hope you watch the videos, as it's very, very different from merely remembering play.

I’ll try to watch the videos,

I'll try to watch the videos, even if slowly. If anything, the comment above will provide a contrast if I find anything that surprises me.

First, thank you all to share

First, thank you all to share publicly this game, with all its reflective process and difficulties. It's a really important post.

I've read thearticle and watched the three first videos. Reading the five problems listed the numerated list and watching the 20 first minutes of play of Session 2, I feel exactly how I felt when I watched mysefl for the first time our Sorcerer Marseilles game – after having played. I was amazed by how what I experienced and what I remembered from the sessions was very different. During the game, my feeling was that Ron wasn't allowing me to play. My feeling was that I was trying to play, but he was constantly saying "ok, but I need to know what your character is doing". Then I watched the videos, and what I saw was me, totally lost in the 5 problems enumerated here. So I'm glad to have a systematic account of those potential behaviours.

I really recommend to the players to watch their videos, even if you don't feel you can't watch them all (I couldn't go through the whole Sorcerer Marseiles playlist). I learned a lot about myself while doing that. I think it changed totally my understanding of what I like in rpg. I think I'm going to re-watch my own game with this post in mind, and the arrow diagram.

Once I saw this in me, I couldn't unsee them. While being GM at Sorcerer, I saw that my old fellow traditionnal players were doing the same that I did. Not stating anything, getting backward in the grey arrow before the resolution of the roll when I was just setting up the situations of the NPC, avoiding the rolls and trying to framing differently the situation through "roleplay". And I can see myself repeating those behaviors, for instance, in the Rod's Sorcerer & Sword game – until Rod made a commentary that made me understood how I was not exercing my agency through various self-explanations ("my character is like that.", "I need some more information", etc.). "Not exercing my agency" meaning: not grabbing those dices and say "damn, I'm doing THIS, NOW".

I didn't realize until now how the Pool highlights very well those processes. I'm not sure I would have understand it without this post, and it put words into things I've seen while rewatching me play.

I am also a "GM" in my social group. I'm pretty sure it's not helping – I'm going for more "not being the gm" for the next games. And maybe time for me that I re-watch all the Marseille Playlist.

Thank you for providing these

Thank you for providing these points.

The GM/player distinction is relevant, but it's not absolutely the core issue, which is simply to see what one (oneself) is actually doing. I learned a lot from that Sorcerer game too.

For my part, in this game of The Pool, I also realized only through viewing that I had not optimized a couple of Pool mechanics – one of which is really important to my own arrow diagram in this post. Specifically, that players should really be the ones instigating conflicts, i.e., the need to roll dice.

The most widely-available version of the game is not absolutely insistent about this:

… but in conversation with James back then, and based at least on my memory of phrasing in the very first two-page version, the rolls do best when they are prompted by something that a player has a character do. It's possible that a GM might say, OK, you are here, they are here too, this is happening, so everyone state an action and roll, but it's better for the "state an action and roll" to be prompted, i.e., initiated, instigated, started, however you want to phrase it, by the player or players, in the initial grey arrow.

The reason why is that solidity at this point sets the foundation for functional play during the next arrows: (1) diminishing or removing the need to see what player-characters are doing in the middle of the second arrow, so merely clarifying what's happening is easy and non-negotiated; (2) having a nice solid bank of both known-but-unresolved and as-yet-unknown things to work with when describing what happens during the third arrow.

A side point: in this game, similar to Tunnels & Trolls way back when, a great deal of this description feels retroactive if you're not prepared for it. But since the precise actions and details weren't yet established, this is now how they are established, and therefore it's not retroactive at all. To be technical, if you're used to IIE+E, with the roll at the +, then I+IEE is horribly jarring, even terrifying. But it's really no big deal; play T&T 5th edition and you'll see how fun it is, also, how frigging Old School for Real it is, i.e., the dice deliver a serious donkey-quality kick. See also the Match in S/Lay w/Me and the inflections in The Clay That Woke for the exact same thing, from authors who were in fact playing in the late 1970s and know what "old school" actually was.

Anyway, that's a big lesson to me for the next time I play the game as either GM or player, which I plan to be quite soon.

This game…

I'm still in the process of rewatching the play sessions, so this comment is open to further review, but I've seen enough to draw a few conclusions.

First, this game was a lot of fun for me. Against my expectations (I HATE antropomorphic animals generally, but the tone here was anything but what I've been subjected to in my dark, dark past experiences) the situation was delightful. The moment the spiders kick in and they start discussing with Claudio's character I started thinking of this as an illustrated british novel rather than something out of Tumblr and it was perfect.

So I had fun (dangerous, difficult word) but that's part of the problem. What was that fun? I enjoyed the situation. I admired the GM's capability to bring it to life. I feel in love with the NPCs. But I didn't really *play*. I've mentioned to Ron how my most recent characters have been tourists of sorts, down their traits/skills, and how I've failed to partecipate in play because I was too busy observing it from the inside. Part of my problem is a having developed a somewhat chronic GM stance (or crouch, or limp, I guess), part is the wannabee designer bug never lets go and I keep catching myself studying the games I should be playing.

It's a big personal failure because this game touched a lot of the topics we've discussed recently on the website, and it was the perfect chance to embrace them and see them in effect. Ron's diagram explicitates something about the I+IEE process that I didn't get from the text and that makes everything clearer, but it can't be traced as the root/core of my problems in play. I admit I tend to discuss an II+EE model as my favourite, but my struggle with finding conflicts in this game was mostly due to me not really being in synch with Teeru. I immediately distanced myself from my character, and I got lost in the arrows.

My understanding of the game now is that a player should be talking until a disagreement is reached about "what's next". I think you can notice in the videos how Ron has to often ask "So, what do you do?" and I think eveytime that happens, there's a strong chance that the player has failed to impart enough momentum to the situation for it to actually become the first arrowhead. I think ideally this should look like someone talking enthusiastically with someone else's having to butt in and saying "Wait wait, I think we need to roll some dice for this".

How explicit the process of going from arrow to arrow should be is an interesting topic. The momentum coming from a volitive, motivated, partecipating player is essential, and you can see on video how I completely failed to have any momentum in most situations. Ron took some blame for play getting kind of stuck in that scene where Teeru and Uropp get into the big street fight on the way to the temple, but it's unfair. I was giving nothing to the game if not a generic "take me to the next scene". This game won't allow that. If the player is proactive enough, you should get a flow of information between him and the other players (GM included) that eventually reaches critical mass and dice are invoked. Had I given anything to that situation – a preferred route or approach, a conversation with Uropp, an immediate action when faced with the new scene introduced – it would have worked great, and the GM would have known how to handle my failure. How can you tell me I didn't get what I wanted, if I didn't tell you what I really wanted?

Part of my problems in finding conflicts stemmed from me making a textbook mistake in terms of attitude: I became mellow and nonconfrontational and did the "nice player routine" – never getting in the way of the GM, never getting in the face of other players, which is precisely how you make everyone's life more difficult – there's a moment at the end of session 1 I think where I can see the glimmer of what it could have been, when I get in Manu's character's face and try to stop him from handling the situation in a certain way… and instead of calling a conflict, I back down, mentally say "Sorry I didn't really mean to actually interact" and shut down. Horrible.

It's interesting how moving the I (Initiation) past the dice doesn't make things vague at all. Intent needs to be really powerful, however, because it can't hide behind things being structured enough already that you can say "my turn to attack" and have done your part. There's a moment in … the last session I think, I'm not sure, not gotten there yet, where Teeru gets to the temple and I'm asked what I do now, and I have this idea about using water magic to distract the guards, and after I have the picked up the dice, Ron starts telling me there's people rushing out of the temple and chaos and whatnot. So I change the course of action and decide I'll do something else instead (the distraction is there already, no?).

I've been self-indulgent about this so far. After all, Ron has changed the situation, or at least I had pictured it as completely different, it's fair to change my course of action! Now, it's easy to see how:

Overall, despite how bad I've been at it, this has been of the most positive play experiences of the last few years. I messed up a lot, learned a lot, and I feel invigorated for going at it again.

I appreciate all of these

I appreciate all of these points. I'd like to focus on one conceptual detail, which I think will not be an actual disagreement.

I want to revise this term, so strongly that I'll even call it a correction. This has nothing to do with disagreement. It is simply acknowledging an uncertainty regarding what will happen next, given what a person is saying, or about to say, what their character is doing.

All uncertainties of play are resolved by someone saying something, specifically, someone who has the authority to do it. The question is which of these, throughout play, include accepted and even celebrated constraints. The most familiar, and relevant in this case, is the participation of rolling dice.

Here, in The Pool, and not particularly unusually, play occurs and eventually includes a moment in which someone really racks up exactly that form of uncertainty which signals the dice to be included in whatever is said next. Most of the time this corresponds with the literary term "conflict," but having thought a lot about this recently, I now consider conflict to be a subset (a common one, yes). It applies here for this game, so yes, a conflict, but let's not forget that we are talking about fictional content, not about "what someone wants," at the table, as a real person. What anyone at this table wants is to see these dice used properly in the context of the right person utilizing them as a positive constraint on his or her proper authority. Wanting this or that specific outcome is a different phenomenon and is necessarily subordinate to, even deliberately negated by what I just described.

In other words, we never roll dice to get what we want in terms of fictional outcomes. That is broken. It has always been broken. Instead, we roll dice so their result will be included in (constrain) how outcomes are stated.

This point feeds into another topic you raised, regarding the scene at the plaza in front of the temple. I should probably wait until you watch it, but … well, here I go. We were at the arrowhead of the first, grey arrow, and I was working with your action-statement to raise a water serpent-shape while staying in that arrow, providing the information necessary for later, regardless of the outcome. You retracted your action statement … much to my irritation; in fact, that was the point during session 4 where I almost clicked out of the call and went to do something else (anything else).

Your dialogue about doing this, both during play and during the discussion after session 4, was very clear: it hinged on the dramatic events you had imagined about the third, light-blue arrow. You were not rolling regarding the grey arrow I was describing, i.e., in the pointy arrowhead of that arrow. You were all the way forward, skipping the dark blue arrow entirely, in the light-blue arrow's arrowhead, imagining how you or someone would be talking about what had happened. Therefore when I provided more information about the grey arrow's content, it interfered with your crystal-ball imagery about the future narration in the light-blue arrow. That's why you revised it, despite my vehement protest during play itself that I was not saying anything that negated your action statement. You didn't care about the grey arrow or the starting part of the dark blue arrow (which was what I needed to do next), which provide the context for uncertainties that defined the roll; you thought you were rolling to "get" the light-blue arrow you were imagining.

I didn't actually table-flip and go watch something unseemly on HBO because I understood where you were coming from, and that you could not, at that moment, understand what you were doing – indeed, were digging yourself deeper with every sentence. I knew the only way for you to understand was for me to stick with it, at the price of my own enjoyment or at least taking a serious hit in my stress and fatigue, and hope for a conversation like this later.

I have no objections to both

I have no objections to both observations. My own summary grossly overlooked how often the "conflict" may be born out of the player's interaction with the rules (and the limits of possible or probable) or even his own statements.

I'd like to add a couple more observations. They're not adversarial or criticism of the text or play, but just thinking out loud as I reflect and interiorize on what we've done (and said).

You mentioned constraints, and I think this is one of the spots where I suffered. I mentioned before about how II+EE is my favourite approach, but then I realized I'm writing a game that is I+IEE (you don't have to say how you do something until the dice are rolled). I think my problem here, tied to me struggling to find out what Teeru actually wanted, is that I didn't feel enough constraint going into the roll (to avoid misunderstandings, I'm not saying there wasn't enough constraint, just that I failed to feel and contextualize it).

From what I can see, constraint in the Pool mostly come from how the GM sets up the scene and how many dice he's going to give you, and little else. There's a moment in play where someone else struggles with deciding what to do with the snake, because they can't apparently decide if they can fight it or not. Maybe play could benefit from a "fair and clear" phase but I realize that for me this kind of very broad conflict can be uncomfortable. Give me "the frog has lept on you and is trying to drag you into the pond to drown you" and I'll feel that my options are limited enough for my creativity to get triggered.

We discussed before about how dice feel really good if the end result of the IIEE and narration is that anything could have happened, but what actually happened feels inevitable once the scene is resolved. I think my comfort zone, right now, for that to happen is to have the dice arrive at a moment where the scene is clearly defined and visualized, and anything that happens after is where things broaden up. This is a place where my experiences with storygaming have damaged my enjoyment of play, because very broad turning into "nothing we said so far limits what we're going to say now" was so prevalent.

But sticking with this, I think I sometimes felt too much freedom and didn't feel the constraints or the context.

I need to reflect on this, because watching the videos I see what you were doing and where you were willing to go (see: me providing my own constraints via questions and requests for details during the "water bucket" scene); I have some work to do on becoming more flexible and less prone to let my own mental artifacts get in the way.

I think something you said is very relevant here: this isn't very different from how everyone is used to play very traditional games. It isn't wishy-washy storygaming, it doesn't do wild and bizzarre things with authorities. This is probably why it can be difficult – it moves the timing of some things a bit, it doesn't give you constraint through instrumentation (what's the serpent's AC? how many HP does he have? how much damage do I do?) but in the end it's the GM saying "here we are" and players saying "then I do this". In this game all the crutches are sandblasted away and a lot of your previous experience can work against you.

One last thing.

Having finished watching the videos, I think one significant element that affected play (not just my enjoyment, but how I was playing) was my cursed luck with dice. We did discuss how failing isn't that terrible in this game – the GM simply picks up the narration, you don't even have some "life points" getting docked from you, so you'll get an interesting new now or well, a failure that really bites (and is its own reward).

But I got to a point where all I got was failures (I think I succeeded… twice, in the entire game?) and based on everything we said, I think there's a measure of "cruelty" in failure in this game. Because the I+IEE structure makes it so that if you get lost in the arrows and skip ahead and don't enjoy the first grey arrow properly (by making sure that in the "I want to" there's enough you that even if the narration goes to the GM your agency will be in clear display)… then unless you succeed you're never really playing.

This makes me think this is the perfect game to teach yourself how to stop fearing dice. You have to grab enough play for yourself before subjecting it to the dice or you may go hours without ever doing anything. Learning how to do that (or perhaps, unlearning how to sabotage yourself in doing that) is the challenge.

Let’s consider the

Let's consider the differences among restraints, constraints, and crutches.

Restraints basically shut you down: there is only one thing to do, or nothing to do.

Constraints change the shape of what is happening or available: reduce or increase, doesn't matter; what matters is that the array is different, or the targets have changed, or the priorities have changed. Even very limited or stopping-point effects can still be constraints – look to see whether they open up new vistas after all, or can be changed.

People who are terrified of restraints fear constraints unreasonably.

Crutches provide so much structure that your best option is always clear. In this, they feel like they shape and guide play, and often purport to be super-realistic or super-sensible … but they are actually restraints in disguise.

That's why your recent interest in complex maneuvers rules for combat are a big alarm warning for me, because I think you were scooting to a safe zone, where the system would take care of you and keep you safe from scary things. Your statements here, fortunately, are recognizing that unless you can play with clarity regarding my arrows without tons of formal subroutines and lists of stuff do to, then all the specifications and formalizations of combat maneuvers are empty bullshit.

That doesn't mean that such rules are always bad and empty. It means the good ones operate as useful, constraint-generating things inside the known and functioning dynamics of play, rather than replacing such dynamics with play-it-without-you instrumentation. But I'm never going to discuss designing such rules with someone who hasn't successfully played Tunnels & Trolls or The Pool, and not as GM either. You have to start without them and then discover when and how your full lunge, stop-thrust, and riposte options are value added.

Rollin’, Rollin’, Rollin’ up The Pool

I don't have much to add vis à vis self-reflection that wasn't already mentioned in the videos. I hope I didn't distract people too much, or ask an excessive amount of questions. I'll watch for those things in my future play.

Regarding the scope of a roll in the Pool, it's still a bit ambiguous to me: the rules say: "The effect of a die roll in The Pool is much broader than the swing of a sword. Anyone can call for a die roll whenever a conflict is apparent or when someone wants to introduce a new conflict. Just broadly state your intention and roll." But what does "broad" really mean? I understand it's more than a simple attack roll like in most D&D, but how wide is the scope? I.e., how expansive (or how specific) can I make my intention? I'm wondering if the Pool could use some clarifying examples or other explicit criteria here. On the other hand, maybe I'm making too much of it: there really was no problem in practice, except maybe for that initial roll where I was confused. And the explanation that the roll comes immediately after the first "I" in IIEE was helpful for me.

Another point I want to mention is the death roll. I admit to being puzzled why this rule was designed the way it was. The only thing I can think of is, perhaps it's supposed to be a measure of how much the other players want the endangered character to survive. Because by the time you have to make such a roll, it's quite likely you'll have little to no pool remaining, and to roll at all you'll need donations from your comrades, who lose those dice from their pools. It seems unnecessarily harsh, though, imo.

It may seem strange coming

It may seem strange coming from me, but I am not particularly intense about exact phrasing and rules in The Pool, as a text. The document we were using (and in one significant rule, mis-using) for our game is one of a stream of versions which appeared 2001-2002. The first one was two pages and featured a character example and illustration, an anthropomorphic cat swordsman for "dark fantasy."

To my frustration over the next year, James didn't play the game and kept revising it in response to random posts and nearby friends, so the effect was to re-phrase or add this or that thing based on whatever someone insisted "had to be in there." One persistent freak-out concerned running out of Pool dice, so that's where the top-it-up rule come from; another was character death (this all happened before The Mountain Witch kind of relaxed everyone about that topic).

From my perspective, which has grown much more forceful over time, is that The Pool didn't get designed in any meaningful playful-play fashion, and remains only a good idea – and as such, we'd all be better off working with the original two-page version, which I happen not to have these days (and would very much like to have, if anyone out there can supply it).

This means I regard the six-page version we used less as developed or designed, as polluted. That doesn't mean I think everything changed from the original is bad, but I don't regard it as designed in the fashion that your phrasing implies: i.e., that we are looking at genuinely designed and published game rules. I don't think we are.

As a game, The Pool's process ended well before it could have developed anything regarding the right pedagogy, e.g., criteria for the breadth of a roll's purview (which as you say is not demonstrably a play-problem anyway), and far, far before anything regarding effective writing, e.g., examples. It is simply not fair or reasonable to expect or request such things from a game which did not receive the playful-play and design process. To put it slightly differently, there isn't a text. There are only notes for proto-alpha, unconstructed playful-play, and as I say, with too much elbowing-in and yipyapping which compromised and probably shut down any process that might have occurred on James' part.

This isn't totally a bad thing. For one thing, it could be a lot worse; I think we're lucky that one of the later indie marketing-sharpies did not scoop up The Pool and publish it in glitzy fashion, crusted over with uncritical advice, fake examples, and retro-GM-control techniques. For another, it's perfectly all right to take the most minimal Pool concepts and use them as effectively our basis for playful-play, honoring their origins as The Pool by James V. West, but recognizing that the whole thing is still, and has never been anything but, the beginning of a design process. That's how I play it.

Oh yes, forgot to mention, or

Oh yes, forgot to mention, or rather, to agree with you that as design, character death in our document is pretty savage and not particularly enjoyable. I think it's a good example of over-determining the importance of death in play, which obviously has a long and fraught history.

At this point – granted, almost twenty years later, so not particularly fair – I see no reason for death in The Pool to be treated differently from any other conflict worthy of a roll. I do think it's a good idea to designate its potential as present or absent before the roll (technically, as part of the arrowhead of the first grey arrow) … the first time I saw this in textual RPG rules was in Castle Falkenstein, 1994, and I said, shoot, that is a very good idea, why didn't we do this all along. I also think separate roll for literal survival, as in the rules we used, is fine. It's the severe exceptional features that have turned out to be unnecessary.

Ok, looks like I was

Ok, looks like I was expecting more from the Pool than its stage of development warranted, I appreciate that.

Regarding the death roll, I'm pretty much in agreement with you. I don't see a reason to make it anything other than a regular roll, albeit with greater consequences.

I did have one thought of a possible variant: suppose, for a death roll only, you could choose to "cash in" one of your traits in order to get those dice back to your Pool, so you could immediately roll them. You then cross out that trait, and (if the character survives) have to add some words to your story explaining the change. For example, in the game we played, I could imagine Booshi saying, "so this is where protecting the innocent got me. F*** this shit! Last time I do that." The +2 trait could be cashed in for 4 dice to help him survive the roll. Of course, I could also choose not to do that, because this trait was so central to his character, I'd rather have him die than make such a radical change (or, I would say that if I were Booshi, I'd rather die than change this value). But either way, the choice is interesting.

Speaking of variations, I was looking over the Ron Edwards variation, in which players could choose to freely give others dice from their Pool. What's your opinion of this one now? Did it make rolls too easy, or was there another reason you decided not to use it?

As soon as anyone used the

As soon as anyone used the term "Ron Edwards variant," approximately 19 years ago, I knew the whole endeavor had wrecked. And the last thing I want to see now is a resurrection of the false, fear-driven, outright stupid spray of "variants." I'm all for what I did or do at a given table, and all about acknowledging the power of the ideas in The Pool. Let's just call it that and stay unconstructed in terms of design. So the technique of sharing Pool dice isn't a variant – it's just something to try or to do, in the framework of whatever else a group may be doing.

Annnnd … right down the rabbit hole we go. All right, I know what I mean isn't clear, or why. I'll reserve the history and unpacking of the whole thing for my course, Playing with The Pool, which will be offered in January. In case anyone's interested, this is the first course I designed when beginning Adept Play.

Anyway, to get to your point about sharing Pool dice, I'd forgotten all about that. I have no general opinion about it, especially not recommending either for or against. I do know that right now, I am especially interested in the fictional content of failure, and the necessity of always having a new grey arrow after every roll.

Please think about this with me for a minute, always having a new grey arrow after every roll, with these in mind:

All of this should be understood as well in terms of Lorenzo's excellent phrasing above:

Its immediate implication is to let the post-roll narration do its damn job without front-loading it (the third arrow, light blue arrow), but here, I want to point to its relevance for the fourth arrow (grey again): that a failed roll still means a new now, a change in this scene. Not as narrating the outcome, but as what happens next or how the whole "shape" of what can happen or what is known changed.

What does that have to do with your question? Everything, as far as my personal "let's learn things" process is concerned right now. I'd like to preserve the harshness or intensity of failed rolls, both as narrated outcomes and as mechanics. I want to see what it's like to play that way once the trauma and artifacts that Lorenzo described so well are absent, i.e., no more identifying successful rolls with enjoyable play. Therefore, at this point, not dodging away, not mitigating or softening them through resource-sharing. Again: this isn't because I think doing so is better or worse design, but because this play-issue is what I'm learning about and enjoying doing so.

I get where you’re coming

I get where you’re coming from, and I find that focus interesting as well.

Before I forget, I do want to at least mention the death spiral. So suppose we assume a beginning character starts out with a pool of 9 dice and a high trait of +2. Let’s also assume that at each roll, they’re rolling 6 dice (so have approximately a 67% chance of success each time), so are gambling 3-6 dice; and assume they take a MoV at each roll.

After 4 rolls their chance of rolling at least one failure is about 80%, so most players will lose 4-6 of the dice from their pool by then. After another 4 rolls, if not before, they’ll probably have lost the rest.

If the player refrains from taking a MoV and takes a die each time, this slows down the death spiral but doesn’t stop it – their pool still gets attrited over time, until it’s gone.

Once your pool is gone, success becomes very difficult – you’d need to get 2 or more dice from the GM at every roll to even have a 50% chance of succeeding.

And if at any point the failure was in a potentially lethal situation, the next roll becomes a death roll, which almost ensures a loss of any remaining pool, and has the problems we already discussed.

Now, I’m not mentioning this death spiral as a critique of the system – I don’t think it’s either good or bad on its own, just a feature that I didn’t realize it had at first, so I thought it was worth mentioning.

It’s not a death spiral. I

It's not a death spiral. I don't even know where to start with you about this, but that is not what happens and it isn't the right term. If it was just about a term I wouldn't care, but talking about it this way turns the whole discourse of Pool-esque design into a terrorized drive to "save" or "counter-act" the loss of dice, like that vile Anti-Pool and Puddle and the rest. Somehow it got past me in the the discussion at the end of our game, probably because I was exhausted from carrying play and from the pushback I was getting.

First, your numbers aren't a model of inevitable decrease; they merely describe how to drive your Pool down, which is to statistically gamble them faster than the rate of recovery. And the trouble with showing the counter-examples is that it looks like I'm demonstrating strategies for how not to do that, as if it were a bad thing … which is the wrong context entirely, some notion of "winning" the Pool. (This was Mike Holmes' outlook, and I think he influenced a lot of people because he scared them with numbers.) So all I'll say is that whether one's Pool goes up, down, or stays the same is completely up in the air and depends on what you do, subject to some probabilities. Change your stated rate of gambling Pool dice and your result changes.

Second, the entire context of "death spiral" only applies if successful rolls are the engine of successful play. Which is profoundly broken, a straightforwardly dysfunctional relationship to the activity. If unsuccessful rolls mean not playing "well" or not playing successfully or not having fun, then you shouldn't be rolling, period. We know where this outlook comes from – the one-stop arbitrary kill, associated not only with loss of investment but often with personal ejection from play. But that's not my problem or anyone's who's interested in enjoying play, as I'm not here to solve or counteract bad play and bad design.

In our game, you didn't suffer from a death spiral at all. First, your probabilities went up after you lost some or all of your Pool dice, not down, as you gained +1's. Booshi did not decrease Pool dice incrementally in such a way that you were less and less able to gain them. You dropped to very low Pool at one point, then you built them up. The subsequent loss was its own phenomenon that could have occurred with or without the previous decrease. No spiral.

Second, let's think about this at a different scale and with different variables. If you had built a RuneQuest character from, say 35% to 90% in their sword attack over many sessions, then at a critical moment in some complex fight, you are still perfectly capable of rolling 100 for a fumble. Then say a 98 on the fumble table says you've critically hit, and the hit location results in the character cutting off their own leg, and they bleed out during the fight and die. Let's even say the whole fight fell apart for everyone after that due to losing their heavy hitter. You might call it being screwed by the dice, but you wouldn't call that a death spiral, right? It's not like his sword skill was going down incrementally first.

Booshi and that guy are the same. The percent is low but because it's a percent it's entirely and always possible, given lethal circumstances. The guy with the sword skill was really good at it but he failed a roll at a particular point and in a way (a hundredth of 1%) which led to a devastating outcome. I would grieve for him and his moment of tragic misfortune, just as for Booshi. They had a good chance, but failure and even death were real and waiting, if you will, in that roll.

This is related to your point above about the harshness of the death rules, which I agree with. I have no idea why James put in such strictures onto the save vs. death roll, but I agree with you that it's not good design. I think it was tied into this notion that "you gotta keep your Pool high," which, as someone who never played the game, he probably accepted at face value from someone else.

I doubt I've convinced you in the sense of a debate, but I do ask you to chew it over for a while. The primary issue here isn't a death spiral but instead a matter of what failing a roll means for this game. And that has a lot more to do with my arrows in the post than it does with a crap, un-fun legacy in the hobby.

So, I want to be clear that I

So, I want to be clear that I was only talking about successful or unsuccessful *rolls* and their probabilities over time, and I wasn’t discussing successful or unsuccessful *play*, at all. My point was quite narrow.

I understand, I think, your point about the important issue being what a failed roll actually means for play. I can imagine many contexts in which I’ll actually have more fun if my character fails a particular roll than if they succeed. However, I’m a bit confused about what you mean in this context; do you mean that in successful play, a player is always indifferent to whether their rolls succeed or not, so whether there’s a downward spiral or not is irrelevant? Or more that, in the case of the Pool, the way rolls function is such that any particular roll’s influence on situation is so robust and so immediate that any overall trend in success/failure isn’t significant? Or something else that I’m not getting yet?

Ok, as I was writing this reply I realized I was making it into a pedantic, semantic argument about what exactly constitutes a death spiral, which is not really that interesting and probably a waste of time, so I deleted that part. Let me instead jump into what my actual experience playing Booshi was; let me describe it from my point of view, then we can analyze it, if it’s worth doing.

When I failed a roll that first time (trying to use scripture to have the frogs back off the pilgrims), I felt intrigued: “Wow! What’s going to happen now?” was my feeling. This was fun, drawing me more into the game and creating suspense, which only increased when Booshi got tied up next to Claudio’s character before “feeding time” was about to commence.

Since my pool was low after that, I refrained from taking MoVs in order to get dice to replenish my pool. This for me was not that fun; although I succeeded in the rolls, it felt subjectively like I didn’t get the full benefit because I didn’t do the MoV. This isn’t a rational feeling: in a game like D&D for example, there’s not even an option to have a MoV (with some informal exceptions like narrating the results of a critical and so on), so trying to claim I didn’t get the full benefit of the roll in these cases with the Pool wouldn’t make any sense. Nevertheless, regardless of the logic of it, it *felt* like I had to hold back on having fun in order to get this mechanical resource. So, I felt some frustration here. I would like to know if this was idiosyncratic to me: Claudio or Lorenzo, if you’d like to share how it felt to have low to zero pool, please do!

Then came the dramatic failure when Booshi faced the giant snake (or hydra or whatever). I once again had that exciting “Woah! What’s going to happen!!!” feeling, which I enjoyed. I did want to hear a little bit more about how Booshi got bit, but I appreciate you were juggling many things at the moment, and were pressed for time.

After that was the death roll, which we already discussed. Overall this was unpleasant, as I felt throughout the buildup to the roll that I really had no chance, and the roll was just an irritating waste of time. The only thing I liked about it was having the chance to give the monologue of death (or whatever it was called) at the end.

Ok, so you made a comparison of this arc with an analogous one using a Runequest character. Now let’s convert this to D&D since I don’t know Runequest (I have one of the earliest versions of RQ lying around somewhere; it came in a box and the rules were in pamphlets, haven’t looked at it in years). So let’s say I’ve got a high-level fighter with a huge attack bonus; he gets whittled down to just a few hit points, fumbles a roll, and then gets hit by a critical and dies. How is this any different from what happened to Booshi?

The difference I see is this: the dice pool is both a resource and a gauge of your effectiveness, while in a game like D&D these things are split – you’ve got hit points, which are a kind of endurance resource, and the attack bonus, which are separate and don’t directly influence each other. When hit points are low, this influences play, often by making it more exciting. It does not reduce your effectiveness at all. When your pool is low, however, play is not more exciting but more frustrating (at least it was for me), and it does reduce your effectiveness as you have fewer dice available to gamble with.

I’m open to the possibility of this simply being an artifact of my lack of experience with the game. I’ll certainly try to play it more and see. But you asked if there was a difference, and that’s how I’d describe it with my present understanding.

I agree that the spiral is

I agree that the spiral is not the real topic. I wrote an earlier comment that still seems to me to be the core of what you’re describing, which is also, for my part, the thing I think I didn’t do well enough in our game. Specifically, the GM’s job is always to hit the next grey arrow, the fourth in line in my diagram, as an entirely new thing. Inside the current scene or transitioning to a new scene, whichever, but always establishing that this roll did change things, from what was happening to what is happening now.

With that in play, then I think failed rolls do fail, but are not ineffective in a particular sense that I think is the real topic at hand. It’s a possible framework that a player may bring to the table, for any game:

I think you can see the issue since you’ve essentially already identified it above: that the player is basically rolling for the chance to enjoy play at all, as they see it. Even if they don’t fall into the trap of thinking of the MoV as “GM for a day,” they are still in a genuinely no-fun frame of mind, and given that the dice can fail, by definition, and that one’s Pool can decrease, they will feel trapped. “I have to roll to get that MoV, and my best chance to get it is to invest high with Pool dice, but it’s so easy to fail, and then my whole chance of doing so is dropped so hard. It’s a set-up to be screwed!”

That’s what I really wanted from this conversation: putting aside the easy label of death spiral (which I think is an important concept and problem, but elsewhere, not here) so we can talk about this perceived trap, which I strongly agree with you is relevant here.

Definitely not the first phrasing. For the second, almost. The last part of the sentence doesn’t fit. A character’s overall trend in success/failure through a sequence of play should always be significant; again, otherwise, there’s no point in rolling dice – or for that matter, in playing with any sort of resolution procedure at all. The second phrasing makes the most sense to me by clipping off its last part, so that it would read, “any particular roll’s influence on situation is robust and immediate,” period. And to nail down the details, by “situation” in this case we’re talking about this scene for sure, if not more; the event might be generally important enough to affect the wider situation of play (“scenario”) but it might not, that’s case-by-case.

If the GM is doing their job with the fourth arrow, then every roll is, as you say, robust and immediate. It’s not just confined to the third, light-blue arrow (i.e., narration of the outcome). The MoV is a curiosity or detail or way to enjoy one another's presence, not a blow-out critical. No matter who narrates, this roll's outcome matters to play as a whole, and even to play as such, because this roll was conducted about that, and whether it succeeds or fails is always effective, has impact, in terms of this scene at the very least. Cumulatively, outcome by outcome, the pattern of success and failure obviously does matter, in fact, it is core to the ultimate/emergent plot that we have created. A failed roll, therefore, is not ineffective in any sense of significance – it’s important that the character did not succeed, at the very least in that particular scene, and often more than that.

The next question is, if the GM is doing this job, whether a given player can believe it, know it, and be present for play in this context. The framework I described above is often deeply internalized and impossible to shake off. I’ve observed many players to be capable of putting on a good-sport, I-can-take-it face when failing rolls, but that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about really caring about success vs. failure as far as one’s character and immediate investment are concerned (thus not indifferent at all), but also knowing that every roll is its own powerful contribution to play as such, and that our play (plot, whatever you call it) would absolutely not have occurred without it.

First, I appreciate your

First, I appreciate your detailed description of the function of rolls, it’s clear and makes perfect sense.

And I think you hit the nail on the head with your description of how players can feel trapped. Certainly I felt a bit strait-jacketed or constrained during the game, although not so intensely that it completely ruined play (overall I still enjoyed it). If I understand you right, you’re saying the likely cause of my frustration is a framework of expectations and hopes that I brought to the game, that are actually quite common, along these lines:

Which leads to this type of thinking:

“…“I have to roll to get that MoV, and my best chance to get it is to invest high with Pool dice, but it’s so easy to fail, and then my whole chance of doing so is dropped so hard. It’s a set-up to be screwed!””

Now for myself I’d phrase these three eventualities a bit differently – my feelings about them aren’t as strong as what you describe – but I’d say in essence you’re absolutely right; my unspoken assumptions going in were that MoV equals the “critical hit” and the most fun, success is ok, and failure is mixed.

Regarding failure, upon reflection I’ve realized my reaction to the failed rolls was mixed, because there are two aspects to them: one, the consequences of the failure in the fiction, which I was fine with (even enjoyed a couple of times) and two, the mechanical consequences of the failed roll, i.e., the effects on the dice pool and perceived chances for future success (and adding bonuses to traits); these mechanical consequences I was unhappy about. The loss of the entire dice pool definitely took the wind out of my sails a bit.

So the question is what’s the alternative; is there another framework of expectations and hopes that would help me and others enjoy this type of play more?

I believe you’re answering that here:

“The next question is, if the GM is doing this job, whether a given player can believe it, know it, and be present for play in this context. The framework I described above is often deeply internalized and impossible to shake off… I’m talking about really caring about success vs. failure as far as one’s character and immediate investment are concerned (thus not indifferent at all), but also knowing that every roll is its own powerful contribution to play as such, and that our play (plot, whatever you call it) would absolutely not have occurred without it.”

But I don’t completely get it. The critical section seems to be that last part, “…knowing that every roll is its own powerful contribution to play as such, and that our play… would absolutely not have occurred without it.”

Let me try to put that in my own words: Yes, the player absolutely cares about their character’s success or failure, that’s part of the fun of the game. But in addition, the fact that they played the character the way they did, and made the rolls they did, was an integral and valuable part of play; this is something to be conscious of and take pleasure in.

Is that along the lines of what you’re thinking?

It looks exactly the same to

It looks exactly the same to me. Which I suppose means "yes," or "good," or whatever, although my approval isn't really an issue here. What remains is to apply it, and especially, if you don't mind my advice, to reduce or stop GMing for a while. (I've already told Lorenzo this for similar reasons.)

If you want to continue this topic, let's do it in another discussion or play-post which applies, maybe one of the other Pool posts if you want to check out any of the videos.

Thank you for taking the time

Thank you for taking the time to explain your perspective, I understand it much better now.

Oldest Pool doc I can find

https://web.archive.org/web/20020604130516/http://www.randomordercreations.com/thepool.html

I have a text file of that , too – anyone who reads this and wants it, let me know

Putting on a clinic over here

Over the course of not quite the last week I have watched all of the videos and read the posts here (probably read the posts too quickly; some re-reading is in order). In the midst of my own play of the Pool and desire to GM it, I just want to say that following along with this group's instance of play and dissection has been immensely rewarding and helpful–I have a lot of things to pay attention to as I play (and not just as I play the Pool), even if I don't have a lot to add to the conversation at the moment.

Although there is this: Restraints, Constraints, and Crutches! My god, yes, especially the part about those who fear restraints being unreasonably worried over constraints. I have seen so much dodging & weaving in play around this stuff, my own and others'.

One thing I want to add as

One thing I want to add as follow up to my comments above: after playing the Pool more, now looking back over my experience with the frog pool game, it's clear to me that at the time I was making too much of the MoV – it meant much more to me than was warranted. Although the MoV is cool, it's really not that big a deal.

I routinely go back to this post and I balk at how much my understanding of play has evolved since then.

The four arrows are all about the execution of outcome authority, aren’t they? Essentially, since The Pool hardly regulates the passage between the arrows, how we do it is entirely ours. In this naked state, what we’re responsible do as players becomes easier to reflect on.

In any case, thanks, Ron, for triggering this change.

The arrows are all a subset or breakdown of outcome authority, with two exceptions.

1. Arrowhead #3 is the distinct category of narration authority.

In a simpler world, narration authority would be nothing special, merely a component of outcome authority … except that in practice, without designated rules to formalize it, play often switches to a different speaking-person specifically for it. I didn’t realize this until after playing the original Pool, which was the first game I know which formalized that switch.

That’s why it gets its own category for authorities, much like backstory is its own category although it’s arguably a subset of situation.

2. Arrow #4 is, in its entirety, going back “up and out” to situational authority.

Yes, definitely, that makes total sense and fits with my understanding of what narration [of outcome] authority is — essentially a commonly-separated subroutine of outcome authority.

I’ve been using this diagram to explain the authorities to the Italians — I think part of this is inspired by a similar diagram I saw in Situation & Story. Does this make sense to you?

https://d2svmg1gkvxbbf.cloudfront.net/original/2X/7/76220d11e9f8f3dac30322fd7f217d80d6c5aa6b.png

I think the first three arrows in your The Pool diagram there should essentially fit as a zoom-in over the “Outcome authority” box.