I will describe two different dungeoneering doctrines and then have a few comments after them. Doctrine, here, means a set of tactics one has available as tools. (The maps are player maps by diog.)

I will describe two different dungeoneering doctrines and then have a few comments after them. Doctrine, here, means a set of tactics one has available as tools. (The maps are player maps by diog.)

The slow crawl

The campaign is Rajamaat 2 and the rules chassis is Old school essentials with advanced fantasy rules. The group has been playing for a while. I am mostly a newcomer to the group, though I have played in a few sessions with them before. We are just going down into some dungeon associated to the god Set, related to poisons, evil, murder, snakes and other such fun things. We proceed carefully, investigate a suspicious painting to no benefit, then find suspicious statues and pressure plates in front of them. Putting up pressure with a ten foot pole does not do anything, so we get a pile of stones from outside, put one of them onto the pressure plate, apply pressure with the pole, and repeate until the plate a triggers: a deadly jet of flame! We figure out some secret doors, are scared of a statue of Set with a sphere of lava lamp -like greenish swirling, get some treasures from there by tying a rope to a table leg and dragging it outside the room before messing with the stuff in case the statue or the sphere is triggered, and so on.

No random encounters thus far. Progress is slow, but steady, though someone does take a risk and get cursed by the statue. Do not steal lava lamps from telepathic statues of evil gods, looks like.

This is the slow and careful dungeon crawling routine. We expect (and find) traps and secret doors, and try to trick our way past possible dangers while getting the presumaed rewards, that is, mostly treasures.

The fast raid

The game is Coup de (main in) Greyhawk and the rules are a work in progress originally loosely based on BECMI D&D, but no evolved to be very much their own thing. Many in the group have played a lot together; I and another active player less with them, but we have shared history in discussing roleplaying, plus then there are more random players coming in once a while. The core group is experienced, with pretty much everyone having been both a player and a referee in wargamey play. My player experience is on the low side; what I write here is new to me, but presumably well known to many of the other players.

The first example of a fast raid is taking over the barbican of Castle Greyhawk. With luck and scouting we managed to get us under the barbican without the enemy (a bandit group) noticing, entered the place, swiftly moved up and assaulted their barracks before they had even figured out we were there. We were victorious, but were afraid the leadership would be too much for us, given our wounded state. The leadership had been arguing on the rooftop of the barbican, which was our luck (the referee rolled openly for if they get their act together up there; they did not). We barred the doors, thinking to starve the enemies before taking them on. Unfortunately, being high level D&D characters (my best guess is fourth and second level), they descended, fell or jumped down and vanished into the night. Nevertheless, we managed to secure a fortified position that has been later used for further expeditions into the castle.

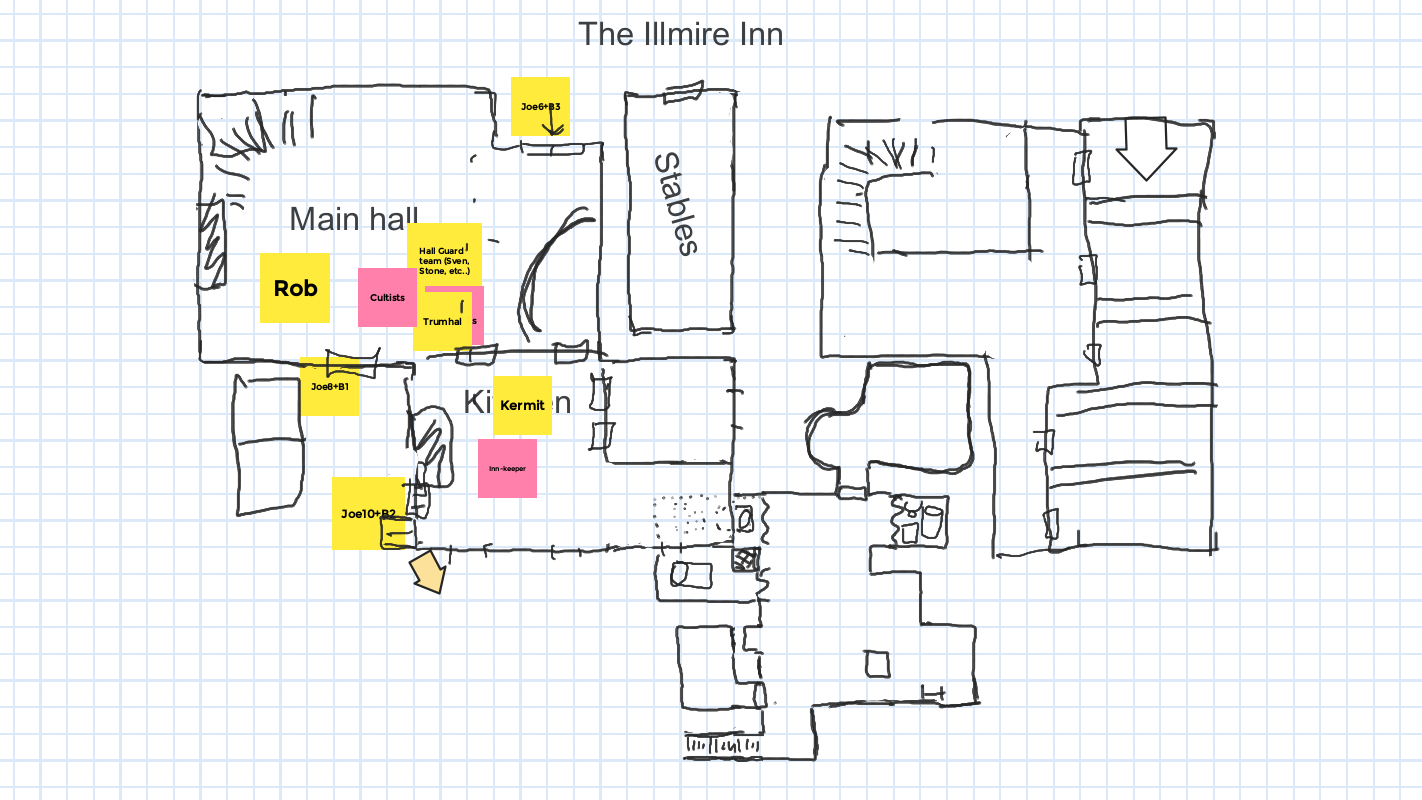

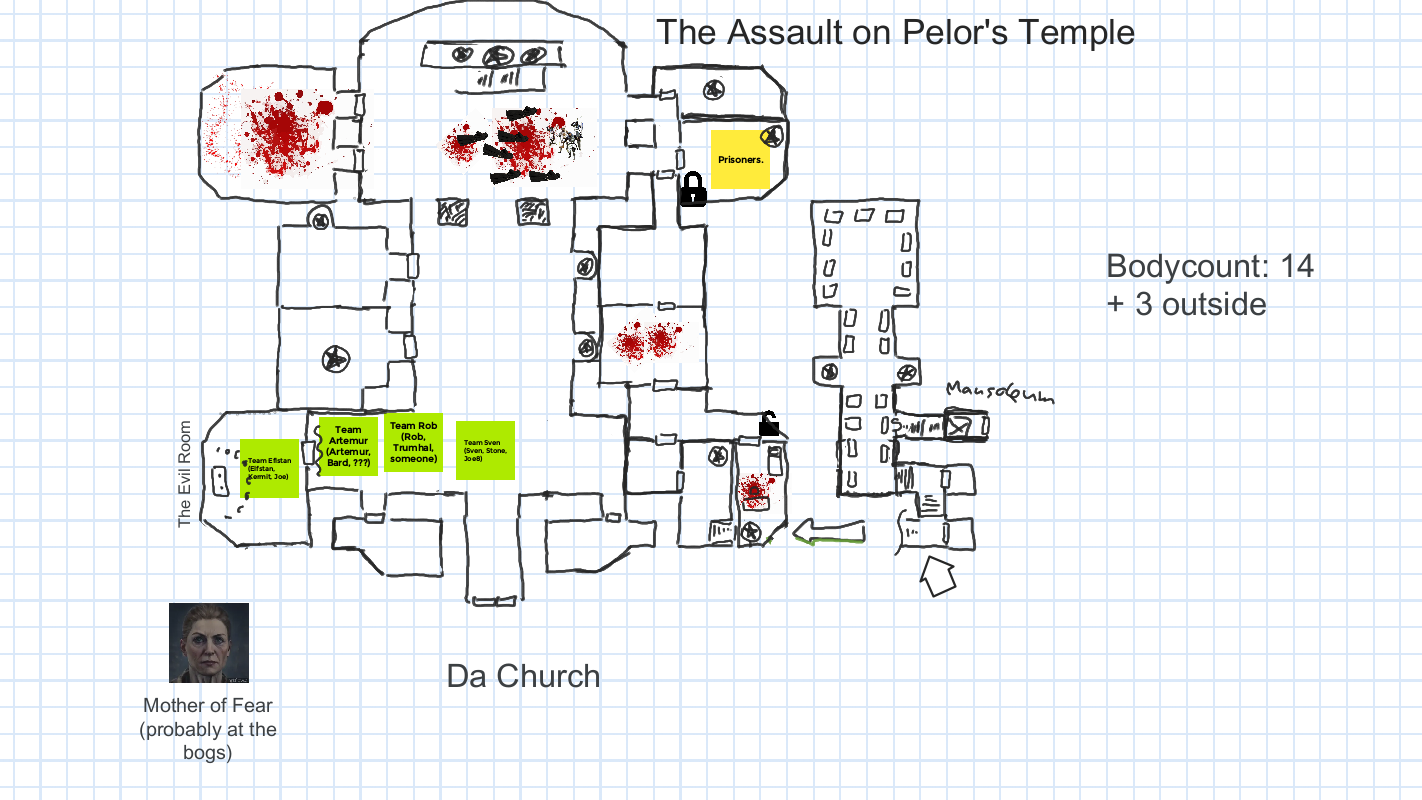

The second example is in Dolmenwood (spoilers ahead). A cult in Illmire captures a hireling of ours, which causes us to take action. We have figured out there is something afoot and the closed and barred church under reparation, as they say, is the obvious place for a cult hideout. Scouting confirms this. We do a ruse to get all their guardians in one place, assassinate them (the alignment of many of our characters is heading towards evil) and enter the church via a dungeon entrance in a crypt. Some confusion with walking dead and we are in, opening a door swiftly, everyone moves in to eliminate all opponents and securing all doorways, and then we move to the next room. The entire place is cleared with no complications, and some prisoners, but not our hireling, are rescued.

The cult also operates the local inn, so most of us get in position to watch it while our thief finds the hireling, they enter the hall, and everyone who tries to run or fight is captured. In the meanwhile a couple of us explain what is going on and get the townfolk to be on our side in case the enemy would try to raise a rabble against us, but everything goes fine.

Unfortunately the cult leader, a former priest, is in neither of these places and manages indeed to escape into a further hideout, which we still have not cracked.

In both of these examples the key was to move faster than the enemy information flow; we were inside their decision making (or OODA) loop and thus could get surprise attacks and not face a concerted force. In both cases the key figures managed to escape; we did not know how great resistance we were about to face and thus did not dare set people apart to stop them, and in the heroic world of D&D it is pretty hard to stop a high level (such as 4+) character from doing whatever they want, at least if you do not have overwhelming numbers or surprise.

Fast and slow

I think that fast and slow dungeoneering are two doctrines. They both consist of a numer of tactics – hard and soft room entry; far, near or no scouting; various problem solving and fighting tactics. Strategy is choosing which to use in a given situation. By listening to rumours about OSR one never hears even the faintest hint of the raid doctrine. You find it in no rulebook. (Or maybe you do, but I sure have not.)

«Don't split the party» is a meme; often splitting the party is an excellent idea. For low level dungeons a large party, totalling 10+ people (player characters, henchfolk, hirelings), seems to be a winning recipe and makes splitting the group even more natural.

A question I am interested in investigating is what other such illegible strategic matters there are in wargamey OSR play. What other invisible choices do we make without ever seeing them?

12 responses to “Dungeoneering, fast and slow”

A correction

From the GM of the Illmire stuff

> One correction, Illmire is not Dolmenwood stuff, it is a seperate module called "The Evils of Illmire" I just happened to place it right next to Dolmenwood stuff on the map.

My bad.

Other factors

I don't know if these qualify as full alternative members to your categories, or if they are intersecting variables, or in-between. Interpret those as you like.

Objective, including:

Flexibility, ranging among:

Unity (to put it most neutrally)

How compatible most of the bulleted items may be with any other depends on specific fictional identities, mostly. Some of the first set of bullets may seem better suited to one or some of the second set, but I've seen every combination across these two sets in published material and at the tables.

My tendency is to think of

My tendency is to think of these (often neglected) factors as matters of scenario set-up , where I mean scenario in the sense of «what are the objectives for the next period of play», not in the sense of a published product; maybe «adventure» is the usual term.

Given the set-up, various tactics might be a good idea. Doctrine is the library of tactics we choose from.

Thinking of things in terms of doctrine is fairly new to me. The slow crawly scouting and the fast commando raid are the two I have learned to formulate. I am pretty sure my play would improve if I could formulate others.

Illusionist habits

I've encountered the following assumptions:

– no henchmen and no NPCs accompany the party into the thick of it (probably stemming from a fear of slow-down and being out-classed or spoon-fed tips, respectively)

– nobody is left behind (similar to Ron's point of either winning or dying)

– no compromises with Evil (not even in the face of Armageddon…)

– no turning to the authorities for help (as a point of pride or because of a perceived futility due to prior, railroaded play)

– never accept the first plan suggested (at least not without examining other options)

– don't trust (or adopt) a plan that would lead to an easy win (it must be too good to be true)

Most of these stem from illusionist play experiences, I think, which train people to follow a ton of unspoken rules required to maintain the railroad / control of the GM.

Maybe? I’m not disagreeing.

Maybe? I'm not disagreeing. It could be wider though.

Some or most of your list also make sense in an overt, non-deceptive team-based "contest" context for play, in which social or tactical pitfalls like "do you trust this guy" or "possible compromise with Evil" are present just like physical pitfalls.

Now … in the kind of illusionist – or let's just say, minimally-actual play in the context of deceptive control, that's essentially a contest too for some players. The rules-savvy or quick-witted player takes it as their required role to counter the verbal control techniques enough to keep from getting entirely screwed or pushed around.

Generalizing about this is tough and probably not a good idea. One play-experience that seems relevant to this was with Zero, in which some friends had been gathered by the one person who'd invited me. The game turned into a bit of a Rorschach test per person, in terms of what they considered the point, "why they would play." One player matched almost all of your listed points, as well as shying away from certain emotional things that are pretty explicit in that game. It kept … not fitting, in the sense that he could have his character do X or whatever, and it never seemed to pay off for him because there wasn't any controlling to defeat or subvert. So it just ended up that his character did X and we just, you know, kept playing with those effects in action.

I'm not saying this to pick on the guy, but to reflect now upon what I see as an overlap between being subject to GM control and being in a procedural and tactical contest with the GM. it's a behavioral overlap rather than the two points of play. As if the player were saying, well, if all this "story" talk is just cloud cover for you running us around in your "drama," then I'll show you you're not the boss of me, then switching to this interpersonal savvy that would be fully suitable in play that's openly and honestly dedicated to tactical contests. In my experience this switch is either pretty hostile or provokes hostility in return.

Again, at the risk of abstracting and generalizing, this would make sense of the odd and very common historical claim that if you're not "story oriented," i.e., compliant with the God-Author's plan, then you must be a "typical powergamer" and polluting this sacred story ground with your childish win/lose antics.

I can see at least some of

I can see at least some of these habits, and at least some of them stemming from dishonesty or struggling against it. I do not yet have the skills to extract any usable doctrines out of them. Maybe this is not a fruitful angle for finding new matters of doctrine.

Regarding fast raids, I

Regarding fast raids, I suspect that the initiative / surprise rules are quite important. D&D 3e, for instance, grants but a single surprise round and even rogues might not be able to capitalize if enemies are immune to sneak attacks. By contrast, AD&D apparently has up to five (!) free rounds for the ambushers as explained by Delta. So I think we might not be seeing a lot of fast raids in many games because the rules limit the effectiveness of such tactics.

Similarly, the viability of certain tactics would depend on the exact procedures involved:

– hit-and-run tactics: rules for pursuit, hiding, tracking etc.

– shock-and-awe tactics: rules for morale

– assassination tactics: rules for morale, leadership etc.

A look at common real-world approaches (terrorism, torture, offering free passage etc.) and an examination of the procedures that would be involved might be fruitful.

The mechanical parts of the

The mechanical parts of the system certainly make a difference, but when it comes to the fast/slow distinction, I would be prone to thinking that the modelling of slightly larger scale enemy behaviour is more important.

If the enemies wait kindly in their set-piece encounters, and make no use of information they get, and maybe even have no ways of getting information, then there is little reason to go fast.

If, on the other hand, the enemy will fortify their position and concentrate troops, prepare an ambush, just outright strike at you with all their force, use extended magical rituals, prepare traps, or maybe even run and take their valuables, then maintaining the initiative (not on a level of combat, but the entire operation) is valuable, pretty much irrespective of whether you get five combat rounds of surprise, or just flat-footed enemies giving you a small extra attack bonus.

In many of these types of adventures the enemy does have a numerical advantage, while the player characters have initiative (they get to choose when to enter the dungeon and enemy does not know they are coming, or at least not when). Giving the initiative to the enemy might lead to them having all of initiative, home advantage and superior numbers. Does not look good.

I agree that reading the relevant real-world doctrine would be helpful. Limited time, much to learn, but maybe one day.

Psychological factors

The removal of morale (starting with D&D 3e) and the trend towards set-piece encounters (when did this start / take over?) have largely eliminated psychological factors (i.e. the question what the monsters might do). This simplifies D&D and gives more control to the module's author (Does that make sense?), making the experience more transitive.

As far as I know, morale has

As far as I know, morale has been written for use at encounter level; essentially, a check on whether some side wants to exit a combat before they are all down.

I agree that removing it simplifies and generally weakens the game, and certainly supports balancing encounters as a design strategy.

From the wargamey perspective I adopt here, morale rules are a way of taking off simulational load from the group (mostly the referee). Without the morale rules as a primary rules heuristic to use, someone in the group has to make decisions concerning when some creatures retreat or run away, using whichever procedures and thought patterns that occur to them. With morale rules in play, one can simply default to them and maybe do something else if they are clearly unsuitable, and the morale rules can also be extended to other contexts like social interaction in general or deciding whether a faction that has suffered losses keeps on or tries to exit (on faction scale, like the entire bandit group disbanding or leaving after suffering losses in several skirmishes).

Of course, many published adventures simply have enemies that fight to the death or fight until ten hit points, rather than encouraging actual thinkin about the faction goals and psychology.

Reading what the D&D 5 Saltmarsh stuff does might be interesting. The AD&D version has both interesting scenarios where enemy psychology easily becomes crucial and clumsy railroading to fix player "mistakes" with the above.

Anecdotally, I’ve found that I can tell a skilled player by the way they control the pace of an expedition. In my circles we usually only talk about “skill” with reference to problem-solving ability, but I think we rely on our ability to estimate risk much more often, and in much more important scenarios.

My most successful expedition (which I intend to write about here) was planned for three months in advance and took two or three further months to actually execute. We cleared a room or two of content per session. We moved so slowly because as we explored new rooms, we would excavate and destroy old ones behind us with our army of laborers and mercenaries. This was probably overkill for the dungeon in question, and cost the lives of many of those laborers. But that didn’t concern me. This was a good “slow” expedition.

The last D&D game I played in was a fast expedition. We were level 1, on a recon mission in a megadungeon, and sprinted through every room, picking up every piece of treasure that wasn’t nailed down or guarded and ignoring the rest. In the end we jumped out of a window and into a lake. Many 1 round combats, no deaths, because we always ran from trouble. Again, a good “fast” dungeon.

By contrast, the last D&D session I ran was for two players (my parents) who were very new to rpgs, and still figuring out how to play, let alone how to play well. Over the course of a year they’ve made it to level 3, and they were spelunking in the moathouse from T1. They moved extremely slowly, checking every corner and listening at every door. I thought this was a good move on their part, as they were surely strong enough to take on Lareth and co. They have 5 “sleep”s between them! They came across some wandering monsters, 7 zombies, and successfully turned them. Unfortunately the zombies retreated down a corridor the players had intended to go down. Rather than hack their way through the zombies, the players retreated from the dungeon entirely. They hadn’t fought anything or taken any damage. I couldn’t understand their decision-making. And unfortunately they hadn’t developed their tactical vocabulary enough explain it to me. (Very likely, if they could have explained their actions, they would have acted differently in the first place.)

I want to say that my players had poor control over pacing. They did not have separate “fast” and “slow” doctrines. We’ll see if this has any knock-on effects.

Your comment suggests that skimming (taking good treasures, avoiding major confrontations) versus cleaning (a methodical approach to get anything and everything of value or interest) is another dimension related to going fast or slow, but not quite the same thing.

Slow skimming is when you are in a place without organized resistance but still deadly monsters or other threats, so you approach with care and sometimes do a maneuver to get some specific treasure out (or maybe just find stuff lying somewhere).

Fast skimming I have not seen or done; could be interesting, and actually worth trying in the Sunday Coup dungeon we are currently playing in. Though it might be a bit too claustrophobic for that.