For a week’s lull in our Väsen game due to many people’s schedules, I decided to bring in a solid and conceptually perhaps challenging game to generate some conversation and comparisons, both with our current game (which we resume tonight) and with the previously-played game, Dialect.

I should clarify that the real title of the game is shock: in lower case, including the colon. The colon is intentionally left blank, and the subtitle is social science fiction. But I’ll use “Shock” in ordinary sentences because it’s more clear.

The circumstances of play had almost hit the impossible point, as I knew this would be one of those difficult combinations of (i) play, (ii) learning how to play, and (iii) understanding play. I planned to start right away and stay sharp throughout, but then we’d waited an hour for a player who couldn’t make it, then a snap decision brought in another player at the last possible moment. So, play was late, stressed, off-plan …

Oh, also, that’s why you’ll see Sam playing with Spelens Hus as special international guest. And it was great to play with you again!

Anyway, we muddled through somehow and did indeed play, but so you won’t think we were all simply dense and fumbling through a swamp at night, I have included a little presentation about the game to start the playlist. I hope you watch it so you will know what I’m trying to convey and what we’re trying to do while you watch the session, and maybe appreciate a little that we did succeed. (And also spot my mistakes, like the math in the first conflict. This game is much, much easier when playing in person and sharing physical documents.)

For reference right away:

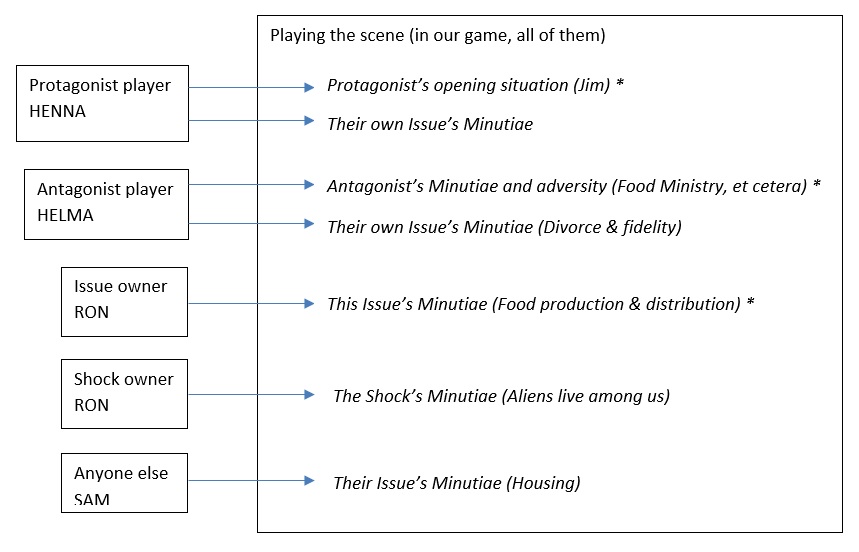

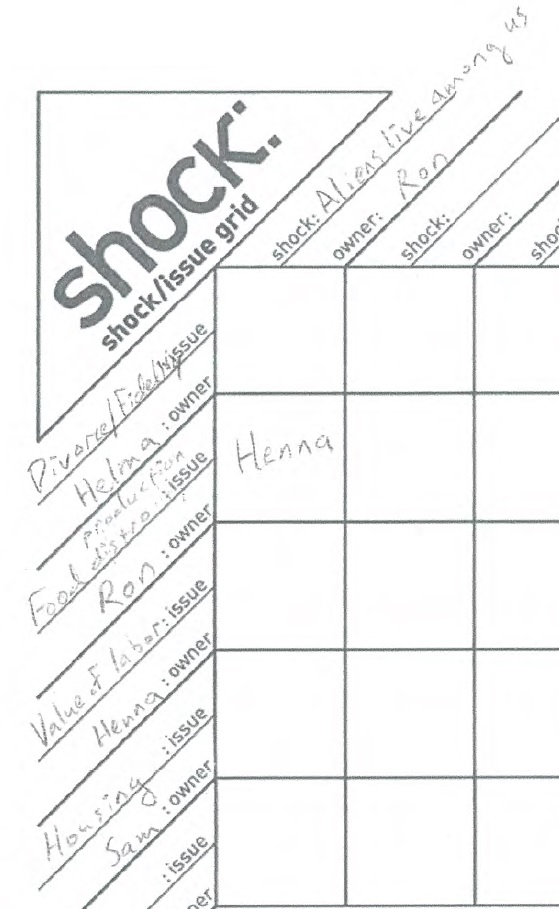

- Our Shock was “aliens living among us,” especially the point that they’d been here a long time and were only recently revealed.

- The relevant Issue throughout play, as we had only one Protagonist, was Food production and distribution – think of this as being “shocked” by the Shock – a whole new food technology had been established worldwide.

- The Protagonist was named Jim, living in Finland, a rather ordinary fellow except that he wanted to establish a non-tech (or rather, not this tech) boutique grocery and small restaurant. His wife Bergit was one of the revealed aliens, too.

- The Food Ministry was generally obstructive as one might imagine, but various corporate machinations were also specifically making goals like Jim’s impossible, as well as promoting anti-alien racism.

As a topic of some interest, we were all a bit surprised at how conventionally uplifting our story became. I can’t speak for Henna, but I do not hesitate a moment in doing so for Sam and Helma, in addition to myself, in that we do not believe that centrist compromise between plucky little activists and sprawling multi-leveled institutions yields the Aristotelian mean of the bestest most goodest policy. But Jim did this very thing.

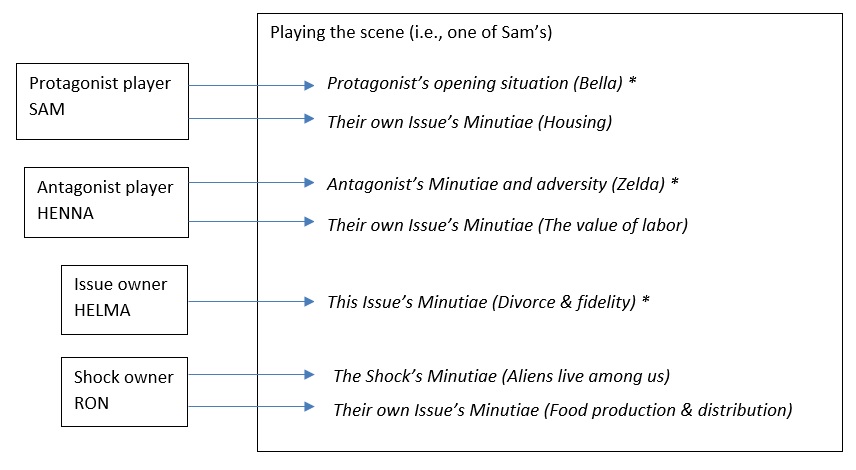

One of the reasons how this could possibly have happened arises from a point I make in the video, that our scenes’ Authorities structure all split the Food Ministry as active Antagonist away from either the prevailing Issue of food production/distribution or the fundamental issue of the Shock (the aliens among us). In other words, the obstructive or difficult aspects of the Ministry, as played by Helma, were no more contextually powerful than Jim. So it really fell more to to the dice and sometimes to the decisions of the Audience than it did to anything Helma could do.

That’s no bad thing, but it’s a good illustration that in this game, “controlling the story” isn’t possible, even to the point of its theme, which I find rather humbling. Stories don’t obey their authors, who are sometimes humbled and sometimes outright indignant about it; we know this is often true for other fictional-producing media, and given our methods in this activity (all of it), I think it’s good news that it happens for us too.

4 responses to “Jim’s Fine Foods”

Social Science Fiction Reflects Our World

I found this to be a very telling actual play. In terms of the choices made about the points of interest, I think the story reflects issues in our own world, which is where SF is at its best. Even big things like Banks' Culture series reflects ideas that we struggle with in our own time.

The end felt both arbitrary and very "let's wrap it up", which I suspect was as much about circumstances in the real world as anything in the fictional world. I am wrestling a bit with the idea that an rpg can have an end goal and still feel organic, which is crazy because all sorts of rpgs have "end" goals. Get through the dungeon. Finish this episode. My question is: with multiple protagonists, could one story be wrapped up while the other is still playing or do they have to come to a place where all the P/A conflicts are resolved in some way?

I also felt there was an extra step of space between player and character. I would not say completely divorced, but detached, observational, and contemplational. Again, that fits with a 60s-70s SF aesthetic. Am I off on that? Was it just an artifact of this session is that baked into the design?

I think the “wrap it up”

I think the "wrap it up" feature is intentional, partly due to the punchy and often not-fully-conclusive nature of the short fiction and films that inspire the game, for which asking the question is really the point. However, not quite as abrupt as you're observing here, necessarily, for a reason that won't make sense until I address your other point.

The separation from character that you're talking about is part of the learning curve. A group or person typically has to go through at least one experience of understanding what their obligations and routines are – especially since they usually shift a lot as we move from Protagonist to Protagonist – before they can start really living and breathing from a character's point of view. The result is a sort of herky-jerky effect in the fiction, including the slightly forced "now the Antagonist attacks" feeling, related also to my advice in the video that you should not close a scene right at the end of a conflict.

As this learning curve progresses, scenes become more relaxed and extended, with a lot more casual dialogue and incidental action. I stress that this isn't just about playing one's Protagonist either, but happens just as much regarding playing one's Issue, Shock, Antagonist, or Ephemera. You know it's happening first when scenes have enough room to allow play with Links as characters who matter, and then when a whole supporting cast, mostly not Links, seems to have walked into play as if they had been painstakingly created beforehand, although they weren't.

To bring it around to your first point, a secondary effect of playing this way is for the endings to become and feel far more causal, more necessitated by multiple events of play in sequence.

Small Contributions With Big Impact

I must be going crazy, because I was convinced I already commented this here, I guess not…here goes.

This game was fun, especially because at points we as a group were doing a bit of struggling and grappling with what we all had to do, which I think is a lot of fun. Its especially nice when it seems like multiple people are struggling together!

I really appreciated the game's effectiveness at making my ~3 small contributions matter a bunch, with the cool rules for the audience member players (it probably isn't called that, hopefully you know what I mean) to influence the outcomes of rolls with the Shock they are in charge of. Because I was only in charge of a single Shock and nothing else, I was basically a spectator for most of the game. But I found it very easy to be actively listening…and it felt very clear to me when I should contribute something. Especially outside of conflicts, it was never something I felt like I had to force in, it felt like I was compelled to contribute by my mental image of the scene, which was kind of cool!

And after making 3 or 4 small contributions, the whole situation resolved in a way that very much integrated what I had said earlier as a vital part. I think its a cool idea to have some players who are not as involved in terms of amount of speaking, but whose contributions are still a major deal. Playing this game in this role, I immediately thought of the possibility for rules for death (I think about these a lot) involving a similarly lesser speaking amount/high impact when you speak.

I hope to get to play the game again in the future!

The role of Audience in any

The role of Audience in any given conflict is an excellent feature, and the game is built so that its number of players is always N-2. It's possible to play the game with just two people but I don't think it's ideal and will have possibly cool but very specific edge-case features, including the unfortunate loss of an Audience die in the mix.

Whenever you have four or more players, there's a chance that, on a given turn, someone will be Audience, i.e., without Protagonist or Antagonist, but also doesn't own the Shock or Issue. This is usually a momentary case, because when some other Protagonist has a turn, that person is probably going to own the Antagonist or Issue or both. At first glance this seems like a limited or minor way to play, to be stuck in, basically … until it's revealed as actually really fun.

Years ago, how much fun became clear to me when we played with a similar setup, with only one Protagonist, and one person was only Audience throughout play. They enjoyed it so much – to everyone's surprise – that we realized it's a feature. Later games with lots more players but not very many Protagonists have confirmed it and led me to think that I'd really rather play that way, not with maxing out the number of Protagonists.

For the record, I think you contributed more than you may recall, so that your Issue (in its role as Ephemera) was a strong, contextual component of our setting, even when the main Issue and other primary system features were engaged in more obvious conflict.